Monitoring the state of our planet has never been more important. Scientific consensus has been established on the veracity of global warming, and a greater need to observe, record and respond to its effects. As technology has progressed, so too has our ability to monitor the planet’s climate, with increasingly advanced satellites feeding data back to Earth. Though the results can often be depressing, their accuracy is vital to scientific research, the global economy and even our fundamental safety and existence.

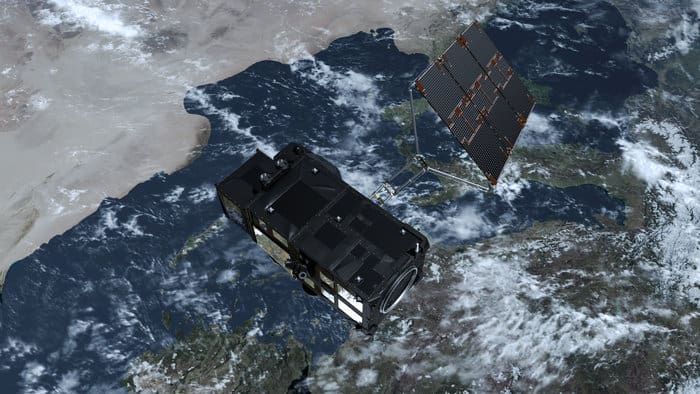

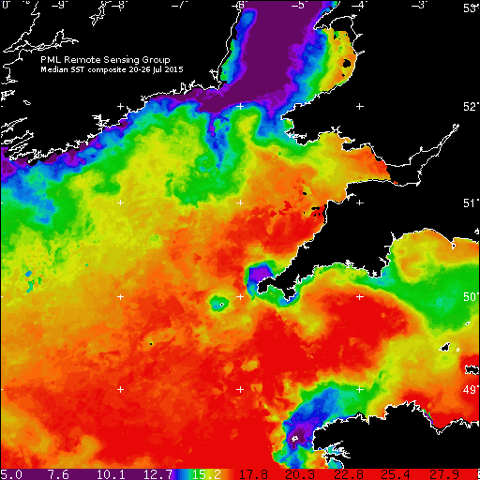

Earlier this week in the balmy surrounds of Cannes in the south of France, I got a chance to see first hand the latest European satellite that will help expand our knowledge on the health of the planet. Sentinel 3A is part of the €4.3 billion Copernicus project - the EU’s Earth observation and monitoring programme. Using a range of instruments, it will measure sea and land temperature and colour, as well as sea topography, providing accurate data with a wide range of applications. Due to launch from outside Moscow on December 10, 3A should be fully operational about halfway through 2016.

The Sentinel 3 programme is overseen by the European Space Agency (ESA), and will ultimately see four satellites manufactured in Cannes by Thales Alenia Space. Sentinel 3B will follow A into orbit 18 months later, with C and D replacing the pair at the end of their service in the 2020s. The projected lifespan of each satellite is 7.5 years, but it’s hoped that they may last as long as 12, and will be fuelled accordingly.

In the cleanroom in Cannes, the engineers and scientists were putting the finishing touches on 3-A before its move to the Russian launch site. Weighing about 1250kg and with dimensions of around 4m X 2m X 2m, the £350 million satellite is roughly the size of a minivan. Its radiometer, spectrometer, and altimeter instrumentation are all located on its Earth-facing front, along with antennas for relaying data and manoeuvring the satellite in its orbit around the poles. The solar array will unfold from the back once in space, delivering power to the on-board equipment.

Having been in development for eight years, there was obvious pride on display at reaching this crucial stage in the project’s life. After all the planning and toil, Sentinel 3A will soon be relaying vital climate data back to Earth, finally fulfilling its purpose. This is, of course, when the huge financial investment begins to pay off. EUMETSAT, the European agency that will operate the Sentinel-3A satellite after launch, provides near real-time access to the marine data while ESA will distribute the land data to users.

Perhaps more excitingly, all data is free to access via the project website within three hours, opening up downstream applications to other users, be they businesses, researchers or amateur climatologists. The open data project exists across the entire Sentinel programme, and has seen considerable success with data from earlier satellites. Almost 12,000 users have registered for access over the past two years, with over 2 million images downloaded to date. All these extra eyes on the planet certainly won’t halt the march of global warming, but perhaps they can help draw wider attention to the climate changes Earth is undergoing. With the Paris talks just around the corner, the planet needs all the help it can get.

Guest blog: exploring opportunities for hydrogen combustion engines

"We wouldn't need to pillage the environment for the rare metals for batteries, magnets, or catalisers". Batteries don't use rare...