‘Not everyone admired Robert Fulton’, writes an anonymous obituarist decades, possibly centuries, after his death. Warming to the task, the writer tells us that ‘many considered him, at best, a consummate opportunist’. We’re reminded that, just as Henry Ford did not invent the automobile nor Samuel Morse the telegraph, neither did Fulton invent the steamship: ‘But like Morse and Ford, Fulton used his insight and energy to turn a challenge of engineering into a large-scale commercial success, thereby transforming thew world’. Built in 1807, Fulton’s Clermont (or North River Steamboat) proved the viability of steam propulsion for commercial water transportation. Under the commission of the then First Consul of the French Republic Napoleon Bonaparte, in 1801 the ‘consummate opportunist’ delivered his ‘plunging boat’ Nautilus – the first submarine; testing of which was carried out beneath the surface of the River Seine at the dawn of the nineteenth century.

Robert Fulton was born in 1765 in the township Little Britain, Pennsylvania in 1765 in a house on the site of what is now 1932 Robert Fulton Highway. With its military connections, the Fulton family was relatively prosperous, and at the age of eight young Robert attended the local Quaker school. Following the death of his father in 1774 and the subsequent loss of the family farm due to mortgage foreclosure, he spent the rest of his adolescence under the shadow of the American Revolutionary War (1775-83), during which time he fades from the record. After the war, we know he moved to the culturally and politically reverberant Philadelphia, where he spent several years as a miniature portrait artist (as well as an apprentice in a jewellery shop), which generated enough money to partially restore the family finances and settle his widowed mother on another farm.

While in Philadelphia Fulton met Benjamin Franklin who sat for his portrait. Although it is unclear how, Fulton secured a letter of introduction from Franklin – who was as the time United States Minister to France – to London’s artistic community. Meanwhile Fulton was suffering from a respiratory illness (probably tuberculosis) and had been advised by his doctor that a sea voyage would relieve his symptoms. And so Fulton killed two birds with one stone and crossed the Atlantic to try his hand as an artist. His entry in Britannica takes up the story: ‘Although Fulton’s reception in London was cordial, his paintings made little impression; they showed neither the style nor the promise required to provide him more than a precarious living.’ He would live in Europe for the next two decades.

While in London working as a professional artist under the patronage of the British-American painter Benjamin West, Fulton became interested in new inventions for propelling boats, as well as getting caught up in the ‘canal mania’ that was sweeping through late-eighteenth century Britain. His interest in tugboat canals with inclined planes instead of locks inspired him to relocate to Manchester, where he studied canal engineering and even filed a patent in 1794, which ultimately came to nothing. Around this time Fulton was also filing proposals to both the British and American governments on the subject of steam-powered boats; a technology that during the past decade had been tested both sides of the Atlantic. American engineer John Fitch had conducted the first successful trial of Perseverance on the Delaware River in late 1787, while the following year Scottish engineer William Symington successfully trialled a steam-powered pleasure boat on Dalswinton Loch.

The power of propelling boats by steam is now fully proved

Robert Fulton (1765-1815)

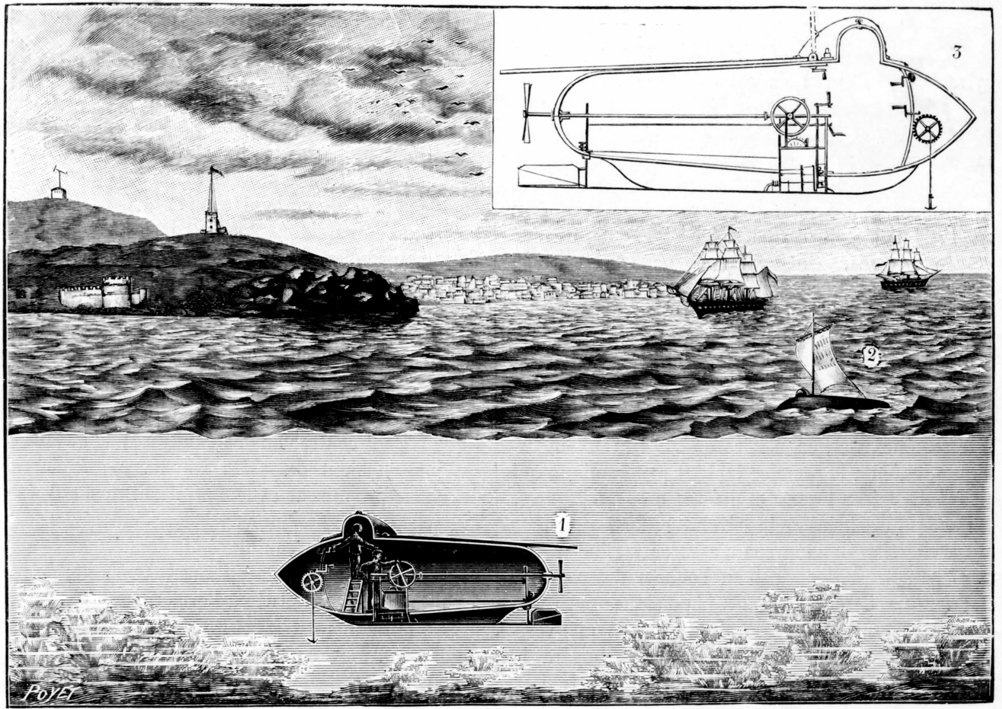

After a stint of canal engineering for the appropriately entitled Duke of Bridgewater, Fulton moved to Paris in 1797 where his reputation as an inventor preceded him. While still active in the art world he started to develop Nautilus, that would become acknowledged as the first practical submarine. This despite coming almost two centuries after Dutch engineer Cornelis Drebbel demonstrated his vessel on the Thames to King James I (who became the first monarch to travel underwater). Fulton’s submarine was intended from the outset to be a delivery mechanism for subsea mines (or ‘carcasses’) and trials proved successful, with depths of 25 feet (7.5m) being reached as well as the destruction of a 40-foot sloop provided by the admiralty. But when it really mattered – demonstrating Nautilus before Napoleon himself – there were severe technical problems. Ignoring the evidence supplied by witnesses of previous successful trials, the leader of the Republic dismissed Fulton as a swindler and a charlatan.

Ever the consummate opportunist, Fulton then switched allegiance and took his invention to the British who offered him £800 to develop the next Nautilus. He relocated to Britain, where he was commissioned by William Pitt the Younger to build weapons for the Royal Navy. But decisive victory in the Battle of Trafalgar under Horatio Nelson in 1805 (without the use of submarine vessels) neutralised the threat of invasion by France, and Britain concluded it could control the seas without Fulton’s further assistance. With the navies of both nations having lost interest in Fulton, his submarine and associated torpedoes, he returned in frustration to the States in 1806, leaving his submarine documentation behind to remain unpublished for more than a century. Fulton never spoke of Nautilus again.

His next venture was to re-establish contact with one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, Robert R Livingston, who Fulton had met in Paris as the US Minister to France. While in Paris the two men had experimented with a 66-foot, 8 horse power, paddle wheel boat. Although the engine broke the hull, they were encouraged by success with further models, and Fulton ordered parts from Boulton and Watt for the construction of another boat on the Hudson in New York. Meanwhile Livingston consolidated his commercial monopoly on steamboat navigation in the state of New York. By 1807 the 150-foot Steamboat was ready.

The vessel that would be registered in 1808 at the North River Steamboat of Clermont was powered by a wood-fuelled single-cylinder condensing steam engine capable of driving two 15-foot paddle wheels, producing steam at a pressure of 2 to 3 pounds per square inch. Its trial run from New York to Albany covered the 150 miles in 32 hours (average speed 4.7mph), not only beating the 4mph qualifying benchmark of the terms of the monopoly, but slashing the time taken by sailing sloops for the same journey by more than half. Fulton was triumphant. Despite his venture drawing what he described as ‘a number of sarcastic remarks’, Clermont had become the first successful steamboat in America. ‘The power of propelling boats by steam is now fully proved.’

More success followed, and within a year Fulton had been granted a patent on his steamboat, while the state of New York awarded him an exclusive right to steamboat transport on the Hudson River. Neither provided him with adequate protection from his competitors, and the Hudson soon became dangerously congested with rival services. And while Fulton managed to defend has patent, the 20-year monopoly that Livingston had obtained and extended was eventually discarded as unconstitutional. Pressing on, in 1811 the Livingston-Fulton steamboat monopoly sent their vessel New Orleans south to validate their monopoly of the New Orleans territory. Fulton also became a member off the Erie Canal Commission which he sat on until his death four years later. In 1812, Fulton completed his last design: the world’s first warship powered by a steam engine. The Demilogos was a wooden floating battery built to defend New York Harbor from the Royal Navy during the short-lived British-American War of 1812. A catamaran with paddlewheel sandwiched between the two hulls, Demilogos was a genuine one-off, but never saw action.

The success of the partnership between Fulton and Livingston paved the way to marriage between the engineer and the statesman’s niece, Harriet Livingston. An accomplished artist and musician, Harriet was 19 years Fulton’s junior, who was presumably unaware of her husband’s colourful private life. There have been fervid speculations about Fulton’s sexuality based on little more than the fact that he once shared a castle with William Courtenay, 9th Earl of Devon who was infamous for his affair with William Beckford, author of the gothic novel Vathek. It is also conjectured that Fulton’s friendship with American poet-politician Joel Barlow and his wife Ruth had evolved into a ménage à trois. Perhaps predictably there is less concrete evidence on these matters than on other aspects of Fulton’s private life. More reliably documented biographical events include him becoming father to four children: Robert, Julia, Cornelia and Mary; and that he died of pneumonia in 1815 after walking home along the frozen Hudson River and falling through the ice.

Lloyd’s Register to lead marine microreactor project

I don´t get it. There is a good case for powering those massive container ships we see in the news (generally when there´s a bridge strike or they get...