It’s unlikely anyone will ever agree on the linguistic roots of the expression that has become the byword for authenticity and quality. But there’s a persuasive case to be made for ‘the real McCoy’ originating in the world of engineering. Behind the phrase lie the achievements of African American engineer Elijah McCoy, remembered today as the inventor of ‘a new and useful’ improvement to a lubrication system that ensured locomotives rolled faster and more economically, while reducing maintenance downtime. By the end of the nineteenth century, the McCoy Lubricator was, according to the Michigan Bureau of Labor and Industrial Statistics, a standard technology on most North American railroads, as well as in other heavy engineering applications such as shipping and mining.

While the greater share of McCoy’s 57 patents – at the time a record for the most held by an African American – were connected to lubricating systems, his powers of innovation were also to make their mark on domestic life in the form of the folding ‘ironing table’ (devised in response to his wife’s complaints over having to iron clothes on uneven surfaces), as well as the lawn sprinkler, which has led to McCoy’s occasional recognition as the ‘Father of Turtle-Shaped Irrigation Systems’. When it comes to the social lubrication of alcohol, his name was further honoured by the Old Taylor Bourbon brand that highlighted its authenticity with the tag ‘the real McCoy’, before arguably undermining the engineer’s professional reputation with: ‘the most famous legacy McCoy left his country was his name’.

Although accounts of Elijah McCoy’s early years vary in detail, most agree that he was born in the British colony of Upper Canada in either 1843 or the year after. According to one of the few biographies of the engineer to exist – The ‘Real McCoy’ of Ypsilanti by Albert P Marshall – he was the son of George and Emilia McCoy, fugitive slaves that had fled as far as Ontario with the assistance of the Underground Railroad, an enslavement resistance network that organised secret routes and safe houses for escaped slaves. Settling in the Colchester Township in Essex County, the McCoys had 12 children who would have been educated in segregated schools. Having fought in the rebel army during Lower Canada’s 1837-38 Rebellion, George McCoy was rewarded with 160 acres of land in compensation for his combatant services; land which would help to generate an income for his family.

Be it known that I… have invented a new and useful improvement in oil-cups

Elijah McCoy (1884-1929)

This revenue was also intended to finance their ‘exceptionally bright’ son’s pathway into engineering. But upon discovering that further education in technical fields was not open to students of African descent, following the advice of a friend George concluded that the best option for Elijah was to send him across the Atlantic. In Scotland he continued his education at the University of Edinburgh, where he was to spend five years as an apprentice before becoming certified as a ‘master mechanic and engineer’.

Between Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the end of the American Civil War in 1865, McCoy completed his stint at Edinburgh before returning to North America. While he had been away his family resettled on a farm close to the recently incorporated city of Ypsilanti in Michigan, and where his father was now established as a successful cigar maker and ‘conductor’ on the Underground Railroad. A newly qualified engineer, McCoy had hoped to find suitable work, but his employment prospects were foiled by the anti-black racism that was endemic in post-Civil War America. As an article on the University of Edinburgh’s website explains: ‘On his return, it was difficult for him to find employment and despite the fact he was highly skilled, he was offered low-skilled manually laborious work, taking up roles such as a fireman or oilman on Michigan Central Trains.’

McCoy’s citation for the Canadian Railway Hall of Fame is more explicit: ‘the discriminatory management of the railroad thought a black man couldn’t be an engineer, and he was hired to work in the boiler room of trains as a fireman’. Smithsonian magazine describes how the fireman’s job entailed keeping the engine oiled to help it running smoothly, limit wear and tear on its parts and prevent overheating due to friction: ‘During every run, a locomotive had to make frequent stops for oiling, at which point, the fireman would jump off with an oilcan in hand and lubricate all of the engine’s moving parts. Without constant lubrication, the heavy machinery parts would grind away against each other, requiring frequent repair and replacement.’ It was an open secret that the railroads’ management needed better methods to make the trains run effectively. But to date no one had come up with any.

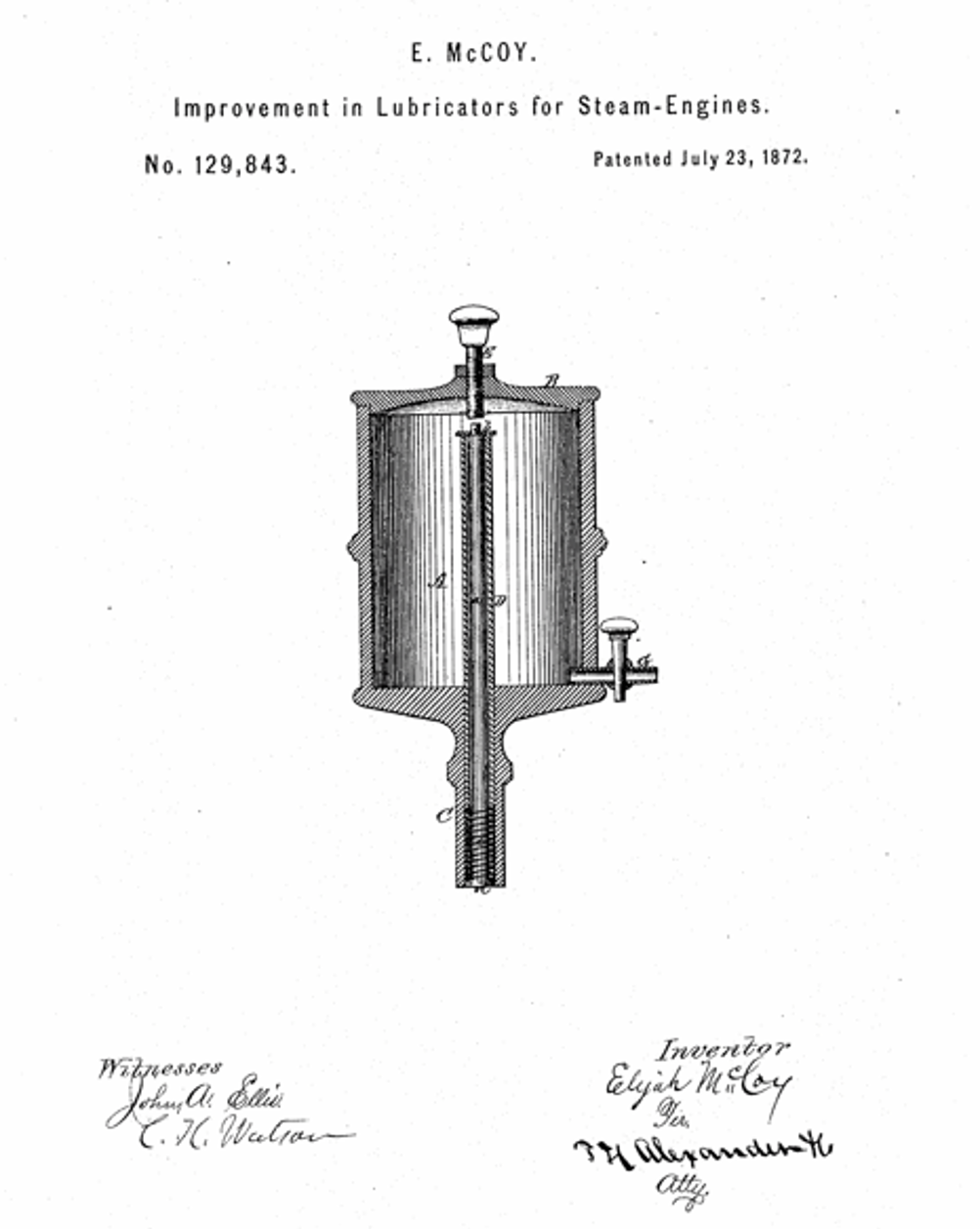

Meanwhile, stuck in a job that was nowhere close to fulfilling his potential as an engineer, McCoy was contemplating these inefficiencies. Realising that the existing oil systems on trains could be vastly improved upon, he set his ingenuity to work in his father’s barn in search of an answer. Pamela German and Veronica Robinson of the Ypsilanti Historical Society take up the story: ‘But it was in his machine shop in Ypsilanti, Michigan, that he invented his famous lubricating cup. Elijah used a piston within an oil-filled chamber and driven by steam pressure to release oil into appropriate parts of the engine. He patented his Automatic Steam Chest Locomotive Lubrication Device (U.S. Patent 129,843) in 1872. And later that year, patented an improvement to the device (U.S. Patent 130,305.) This new device lubricated the engine while it moved, thus eliminating the need for time consuming and expensive stops to lubricate’. The authors see this period of McCoy’s work as ‘Elijah’s crowning glory as an inventor. It didn’t take long for McCoy’s invention to revolutionize the railroad industry’.

Neither did it take long for the name McCoy to become a generic term for automatic oilers not just of his own invention, but also for the many imitation products that had started to flood the market. Furthermore, if the enthusiastic customer endorsement of one William Gardner Shipman is anything to go by, McCoy’s product was the undisputed market leader in terms of quality: ‘I have been using Elijah McCoy’s Patent Lubricating Cup for some time and pronounce it to be the very best lubricating cup I have ever used’. Other engineers felt the same way, and when specifying the component would demand to know that the lubricator on their machinery was ‘the real McCoy’. And so, as German and Robinson explain, the phrase entered American culture ‘to mean the real thing, the genuine article’. However, they take great pains to point out, ‘though many sources claim to be the basis of the phrase, scholars cannot accurately pin the origin of the term to just one of them’. Other theories concentrate on the quality of smuggled alcohol during Prohibition when drinkers, suspicious of dilution would call for the wares of rum runner William McCoy, known for never watering down his product.

Despite the railroad engine lubricating cup and its variants being a pinnacle in McCoy’s career he would never surpass, he continued to invent and innovate for the rest of his life. And while we still feel his unsung influence every time we iron a shirt or use a sprinkler to water our lawns, his place in the history books is guaranteed only by a single component and his name itself. But there is one factor all his inventions have in common, which is that they failed to make him wealthy. Lacking the financial muscle of third-party entrepreneurs to underwrite the mass production of his engine lubricators, he was left with no option but to sell his patent rights to investors that would make millions from McCoy’s work. In 1920, along with a group of financial backers McCoy, at the age of 77, formed the Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company. The name McCoy was proudly stamped on all the company’s lubricators, which by then were extending beyond the United States into a global market.

Smithsonian remarks on how, as with ‘many other black inventors, McCoy faced racism and exclusion in his work, but his lengthy career was a successful one’. Towards the end of his life, following a car accident, McCoy and his wife relocated to Detroit where, suffering from dementia and hypertension, he died in the Eloise Infirmary in Nankin Township (now Westland) at the age of 86. His grave marker in Detroit Memorial Park East reads: ‘Mechanical engineer and inventor of many useful mechanical devices. His invention of the automatic lubricating cup made possible the development of the modern steam engine.’

Breaking the 15MW Barrier with Next-Gen Wind Turbines

Hi Martin, a wind turbine blade functions very much like an airplane wing in a climb. Obviously in one case the air is moving and the other the air is...