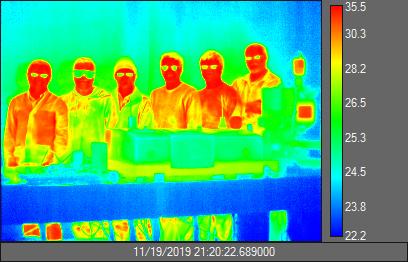

The ultrathin coating is made from samarium nickel oxide, a tunable material that has some unique properties in certain temperature ranges. A general rule of physics is that objects grow brighter as their temperature increases. This allows infrared or thermal cameras to detect people and vehicles based on the heat they emit. But the new coating does not exhibit this regular linear relationship with heat and light and therefore has potential for camouflage devices or even clothing to enhance personal privacy.

Thermal imaging detects mental strain on pilots’ faces

Graphene-based sensor has potential for high-resolution thermal imaging

"This is the first time temperature and thermal light emission have been decoupled in a solid object,” said Mikhail Kats, professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“We built a coating that 'breaks' the relationship between temperature and thermal radiation in a very particular way. Essentially, there is a temperature range within which the power of the thermal radiation emitted by our coating stays the same."

According to the research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that temperature range is currently limited to between 105 and 135 degrees Celsius. At these temperatures, the level of thermal radiation the coating emits is the same. This is because the coating’s emissivity - the degree to which it emits light at a given temperature - actually goes down with temperature and cancels out the intrinsic radiation. And while the current range is restricted, the team behind the discovery believes that further development could lead to useful practical applications.

"We can imagine a future where infrared imaging is much more common, negatively impacting personal privacy," said Alireza Shahsafi, a doctoral student in Kats' lab and one of the lead authors of the study.

"If we could cover the outside of clothing or even a vehicle with a coating of this type, an infrared camera would have a harder time distinguishing what is underneath. View it as an infrared privacy shield. The effect relies on changes in the optical properties of our coating due to a change in temperature. Thus, the thermal radiation of the surface is dramatically changed and can confuse an infrared camera."

As well as engineers from UW-Madison, the work featured contributions from Purdue University, Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

Rail passenger numbers declined from 1.27 million in 1946 to 735,000 in 1994 a fall of 42% over 49 years. In 2019 the last pre-Covid year the number...