I try to maintain a degree of scepticism whenever I’m told engineering graduates are high earners. Firstly because so many engineers will tell you that they’re underpaid. And secondly because the figures used to claim salaries are high are usually broken down by the subject studied at university not the actual job being done.

FOR AN UP-TO-DATE ANALYSIS OF 2018 AVERAGE ENGINEERING SALARY LEVELS CLICK HERE

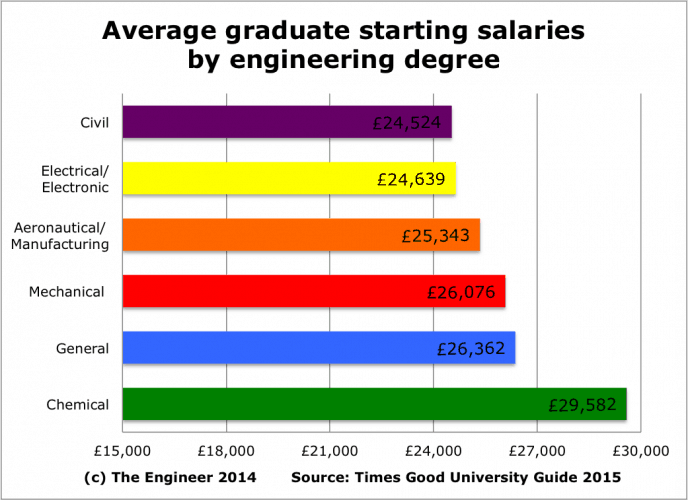

Figures released this week by the Times Good University Guide fall into this category. They show that six of the top ten highest earning subjects based on starting salaries are engineering disciplines.

Chemical engineering graduates earning on average more than anyone except dentists, with a mean starting salary of £29,582. This was followed by general engineering, mechanical, aeronautical and manufacturing, electrical and electronic, with civil coming bottom of the pile (but still better off than almost all non-engineering subjects).

However, these figures suffer the same limitations as many that have come before them. Simply put, engineering graduates may be among the highest earners but that doesn’t mean engineers necessarily are.

We know that only around 70 per cent of those who study engineering go on to work for a company whose primary activity is engineering (according to the Higher Education Statistics Authority). That could mean that many graduates go into higher earning sectors but also that others work for engineering firms in non-engineering roles such as business, management or even sales. And mean figures like those in the Times guide can be skewed by a small number of very high earners.

But, also released this week was another figures that counter this argument. The annual What do graduates do? report from the Higher Education Careers Service Unit (HESCU) found that average salaries for engineering graduates tend to be above those for other subjects because of the larger proportion of graduates working in full-time engineering roles.

Among mechanical engineering graduates, for example, 64.2 per cent surveyed were working as engineering professionals (not just in engineering companies) and only 22.9 per cent were in other professional roles, with just 8.4 per cent in business, finance or management compared with 13.2 per cent for all graduates.

This follows what we know about the proportion of engineering graduates who actually swallow the blue pill and enter the financial services industry: it’s just 2-3 per cent – half the graduate average.

There are of course those who will view the average starting salary of a mechanical engineering graduate of £26,076 as low, or at least not relatively high. After all, it’s about the same as the median salary for the entire workforce – and far less than £40,000-plus offered to some graduates in finance.

But part of the problem here is that our view of professional salaries is massively skewed by the very small number of people (less than 1 per cent of earners) in finance and management who receive more than £100,000 a year, or even the 5 per cent who earn more than £50,000 a year (which includes many engineers).

Large companies in the City may typically offer a small number of graduates much more than £26,000, but the average graduate starting salary according to HESCU is just £18,615-£22,785 – significantly less than the average received by those who study engineering.

And while it’s commonly believed that the other professions typically pay far more handsomely than engineering in general, a look at the figures suggests that for most individuals this isn’t true.

According to the Office for National Statistics’ Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, the median salary of an engineer is £38,428 whereas for solicitors it’s £38,271 and for chartered accountants it’s £34,745. Even architects, who typically train for twice as long as engineers and probably receive twice as much prestige, receive a median salary of just £35,000.

What none of this answers, of course, is the question of whether the salaries received by engineers reflect their level of training, the demand for their expertise and the social value of their work. Engineers and solicitors may earn the same on average, but you don’t hear regular complaints that there’s a shortage of lawyers.

Radio wave weapon knocks out drone swarms

Probably. A radio-controlled drone cannot be completely shielded to RF, else you´d lose the ability to control it. The fibre optical cable removes...