While governments around the world work to different timelines for the day that their countries will phase out combustion engine vehicles – the EU remains committed to 2035, the UK has reverted back to 2030, and the US will likely be further away than ever if the Republicans win the next election – and despite the discussion around the merits of synthetic e-fuels to power them in the future, it is absolutely clear that the best way to make transport more sustainable is to electrify.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) believes that with the current growth in the electric vehicle market, oil consumption will fall by 6 million barrels a day by 20301, so it is self-evident that EVs are a key enabler to achieving net zero emissions by 2050. One of the key recommendations the IEA makes to ensure that this happens is the establishment of ‘secure, resilient and sustainable EV supply chains’ but with China currently supplying around 90% of the world’s cathode active materials – which are critical because they determine the battery’s overall performance, durability and cost – it’s clear that fundamental changes are needed to industrial policy.

In determining the best route forward, we should apply the lessons learnt from the past: the lithium-ion battery was invented in the UK but the strategic importance of manufacturing them locally was overlooked. This is why, even today, we have just one gigafactory – with a capacity of less than 2GWh – when the UK alone is expected to need 100GWh by 20303. It takes around five years to design and build a gigafactory4 but in the urgency to get them under construction we must ensure that in parallel, an optimal supply chain is established in order to make the whole infrastructure fit for purpose and future-proof.

The semi-conductor crisis cost the European auto industry €100 billion5, and led to vehicle manufacturers re-evaluating their entire supply chains from end-to-end instead of focusing only on what their Tier Ones were making. We believe the same outlook is needed for batteries, with close scrutiny paid to the sourcing not only of the cells but also the electrodes, and the materials used to make those. While the shortage of chips was caused by a drop in production and then supply being prioritised to other sectors such as consumer electronics, the effects of any constraints made to the current shipment of batteries, cells and cathode active materials from China would have a similar effect.

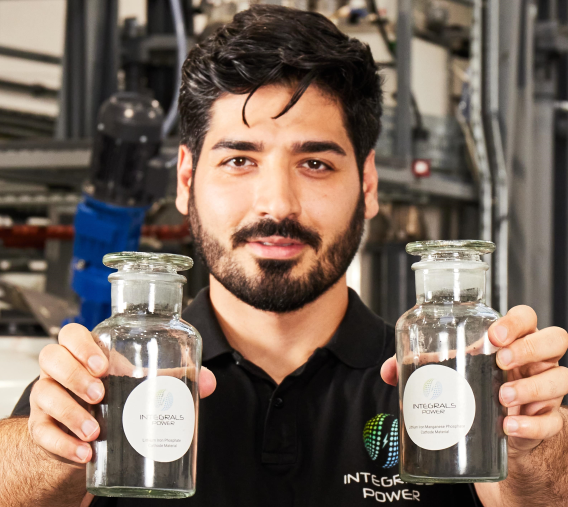

In 2023, the UK government at the time stated that ‘China’s dominance over large parts of the battery supply chain leaves battery makers exposed should the country choose to restrict exports of battery materials and components.’ This is why we set up what we believe is the UK’s only pilot plant making cathode active materials for Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) and even more advanced Lithium Manganese Iron Phosphate (LMFP). Not only are they less costly and more sustainable than Nickel Manganese Cobalt chemistries, they enable us to source our raw materials from Europe and North America. And we’ve developed them at a molecular level using pure materials rather than starting from bulk precursors as most Chinese suppliers do – because those precursors often contain impurities that impair the efficiency of the battery cell, and recycling at end-of-life. They are then manufactured using a unique modular process that can be readily scaled up.

This enables us not only to deliver production-intent samples for cell manufacturers and OEMs to test and evaluate, it also means that customers who want to use our materials in series production will be able to quickly build up the facilities they’ll need, which is vital given that LFP now accounts for more than 40 per cent of EV battery demand worldwide. That share will continue to rise as OEMs strive to make EVs more affordable.

Legislation is also encouraging the strengthening of supply chains and the reducing reliance on China, with both the Inflation Reduction Act in the US and the UK-EU Rules of Origin regulations requiring an increasing percentage of the battery’s value to be sourced locally in order to avoid tariffs. The battery passports that will become mandatory for EVs imported into Europe from 2027 – Volvo claimed a world-first for the one it created earlier this year for the new EX90 – will also make the supply chain more transparent to consumers because they’ll be able to see where the raw materials in their EV batteries come from.

Even if the breaking-ground ceremony for every new gigafactory planned for the UK and Europe were happening today, they’d only be coming online just before the end of the decade, which will make it extremely challenging to support the timely phasing out of combustion engine vehicles with locally-made EVs. It will take massive investment and strong political support to accelerate their construction, but we must attach the same importance to the parallel development of a secure, transparent, and sustainable supply chain if we are to remain on track to achieve net-zero by 2050.

Behnam Hormozi is founder and CEO at Integrals Power

1 https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport/electric-vehicles

2 https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-vehicle-batteries

3 https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/42201/documents/209779/default/

4 https://www.faraday.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Faraday_Insights_2_update_July_2022_FINAL.pdf

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...