Inspired by the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower lanyard, Dr Timothy Neate and Humphrey Curtis from KCL worked with patient groups and charity Aphasia Re-connect to design ‘InkTalker’ and ‘WalkieTalkie’, discreet and wearable electronic badges that act as a conversation aids for people living with complex communication needs (CCNs).

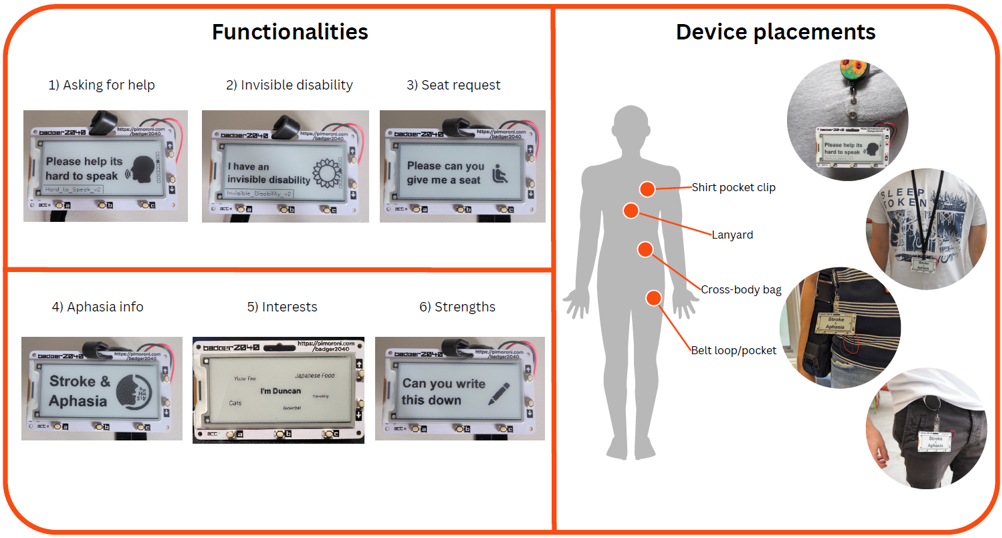

InkTalker displays a series of pre-loaded phrases for conversational use, while WalkieTalkie presents an easy-to-use platform displaying customisable text.

CCNs refer to a broad range of impairments that can result in difficulties speaking, reading and writing, making everyday conversations with strangers and social navigation more challenging.

These can be caused conditions such as dementia or aphasia, a language impairment often caused by stroke, and have been shown to lead to increased risk of depression, psychological stress and poor quality of life.

There are however tools to help people living with aphasia to ‘communicate in the moment,’ such as TfL’s “Please Offer Me a Seat” badges, or cards which say, “I have had a stroke” and provide further information about how to communicate.

They might also use ‘high tech’ augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices like voice communication systems to produce speech, which typically take the form of tablet applications that read input text aloud.

However, the researchers said that these traditional tablet devices are often abandoned as they tend to attract stigma because of their visibility and can block non-verbal communication like body language. Low-tech solutions like TfL’s badge, while less visible, can also result in stigma as they fail to add context to onlookers’ pre-conceived ideas of who should be offered a seat and can only be used in limited situations.

By offering a discreet and customisable form of communication, the researchers hope that the new prototype can avoid the stigma associated with bulkier devices while presenting a flexible aid that people living with aphasia can dynamically change to suit their situation.

By providing a visible solution that users can wear, the device also helps lay clear expectations of disability during conversations with strangers.

In a statement, Dr Timothy Neate, lecturer in Computer Science at KCL and principal investigator of the study, said: “Aphasia is an invisible disability that, while disruptive to people's lives, doesn’t enjoy much public awareness. This can mean that people living with it can face stigma when trying to use the very devices that have been made to help them communicate.

“With InkTalker and WalkieTalkie, you could just as easily ask someone ‘can you help me write this down’ when asking for a phone number, or ‘can you help me get to Tottenham Court Road’ if you lose your way in the city – empowering those who may traditionally find it difficult to speak up and react to life’s dynamic needs. Designing AAC devices alongside people living with CCNs is vital for ensuring these technologies achieve that goal.”

Looking ahead, the research team hope to develop interactive displays in public transportation to help remove communication barriers for people with aphasia further, on the estimated 1.35bn annual passenger journeys on the London Underground.

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

Ground effect fans were banned from competitive motorsport from the end of the 1978 season following the introduction of Gordon Murray's Brabham...