Robot given sense of smell with biological sensor

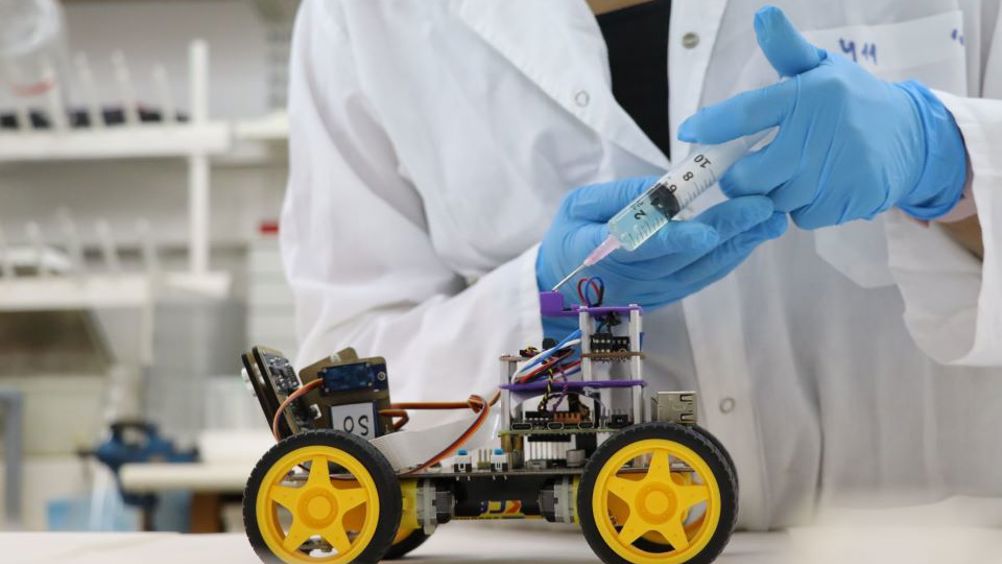

Researchers have developed a robot that can smell with a biological sensor that sends electrical signals in response to the presence of an odour, which the robot detects and interprets.

In this new study from Tel Aviv University, the researchers connected the biological sensor (the antennae of a desert locust) to an electronic system and, using a machine learning algorithm, were able to identify odours with a level of sensitivity 10,000 times higher than that of a commonly used electronic device. The researchers believe this technology could eventually be used to identify explosives, drugs, and diseases.

The research was led by doctoral student Neta Shvil of Tel Aviv University’s Sagol School of Neuroscience, Dr Ben Maoz of the Fleischman Faculty of Engineering and the Sagol School of Neuroscience, and Professor Yossi Yovel and Professor Amir Ayali of the School of Zoology and the Sagol School of Neuroscience. The results of the study have been published in Biosensor and Bioelectronics.

Dr. Maoz and Prof. Ayali explained that man-made technologies still can’t compete with millions of years of evolution.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...