Researchers in the Penn State Department of Architectural Engineering have studied how building inspectors make their safety assessments by analysing their gaze patterns with eye-tracking software. The eye-tracking data could then be used to code autonomous systems, such as drones.

The researchers' results were published in Scientific Reports.

“We are looking for a way to capture how an inspector thinks and makes assessments on a building site to understand their intentions and diagnostic choices,” corresponding author Rebecca Napolitano, assistant professor of architectural engineering, said in a statement. “Studying where they look, and for how long, at certain points on a building can help us do that.”

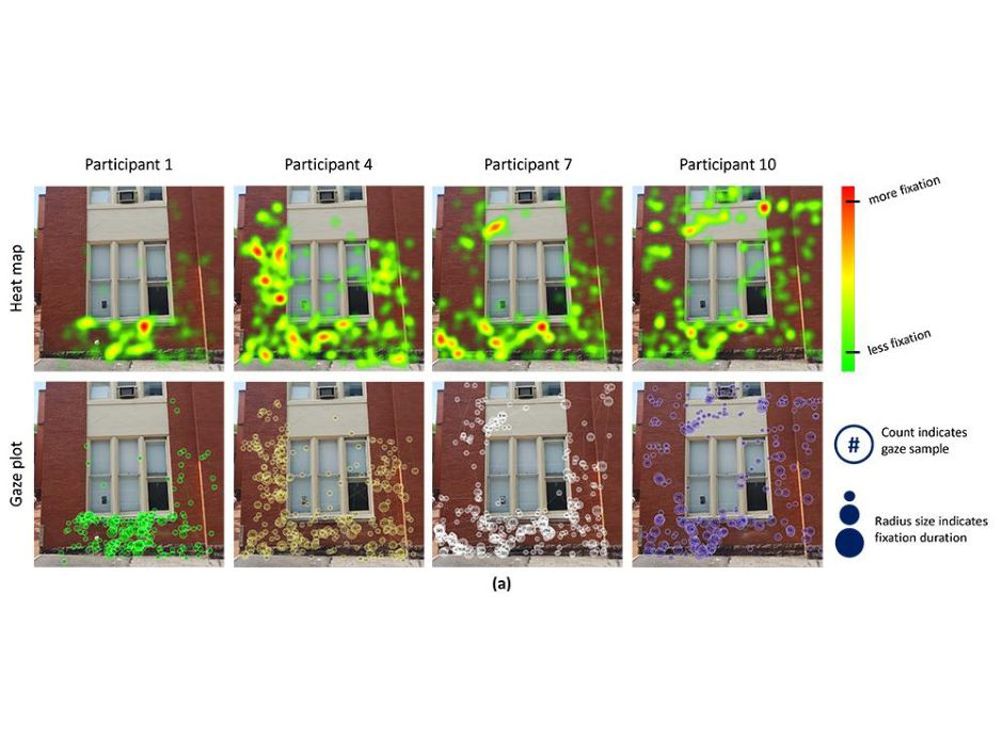

Ten architectural engineering graduate students were tasked with assessing two building facades while wearing Tobii eye-tracking glasses. The glasses have two cameras to measure movements and positioning simultaneously. One camera faces the object, and the other is trained on the user’s eyes to measure pupil dilation and gaze direction.

They were given unlimited time to assess two sections of the facades of two steel-framed buildings in central Pennsylvania, which were chosen due to observable issues including plant growth, peeling paint, degrading bricks, cracks, water cooling and intrusion, and erosion at the foundation.

The participants - who all had some building diagnostics experience and received the same training ahead of the experiment on building inspection - spent varying amounts of time observing different points of the facades. Some missed more obvious issues and focused for long periods on smaller issues, such as cracks.

“Some of the issues were more or less obvious, and eventually everyone found most of the same things, but their approaches to the exercise were very different,” Napolitano said. “We learned that people, depending on their backgrounds, have biases when looking at structures.”

Someone accustomed to looking for certain issues, such as water damage, will spend more time on that particular issue, Napolitano said.

The broad differences in how people assess the buildings present a challenge for coding drones to perform the same inspections, the researchers said.

“It would be hard to take an average of all the data since the study participants had such different results,” Napolitano said. “But it is one small step in understanding how inspectors think, with the long-term goal of creating an algorithm to inform a drone.”

The US National Science Foundation supported this work.

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

What a fun demonstration. I wonder if they were brave enough to be in the car when it was first turned over. Racing fan cars would be an interesting...