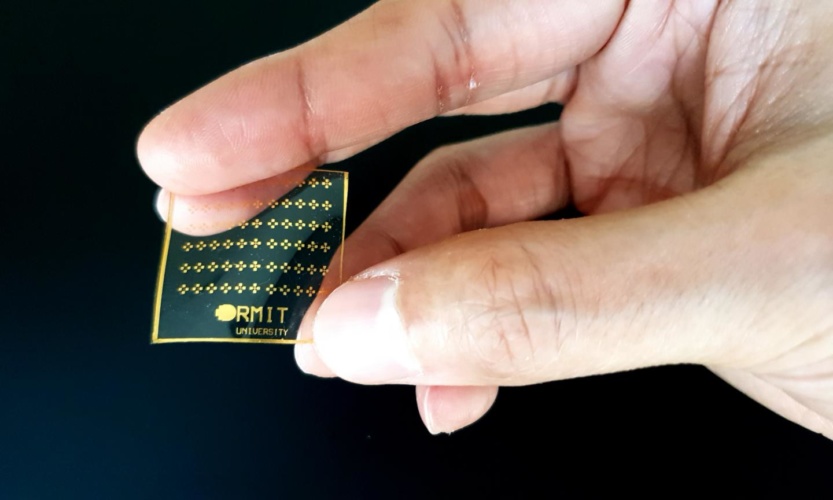

This is the claim of researchers at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia whose prototype device mimics the body's near-instant feedback response and can react to painful sensations with the same speed that nerve signals travel to the brain.

AISkin gets a grip on human skin sensations

Artificial skin enables emotive tactile communication

Lead researcher Professor Madhu Bhaskaran said the pain-sensing prototype was a significant advance towards next-generation biomedical technologies and intelligent robotics.

"Skin is our body's largest sensory organ, with complex features designed to send rapid-fire warning signals when anything hurts," Bhaskaran said in a statement. "We're sensing things all the time through the skin, but our pain response only kicks in at a certain point, like when we touch something too hot or too sharp. No electronic technologies have been able to realistically mimic that very human feeling of pain - until now. Our artificial skin reacts instantly when pressure, heat, or cold reach a painful threshold.

Bhaskaran, co-leader of the Functional Materials and Microsystems group at RMIT, added that the prototype is a critical step forward in the future development of the sophisticated feedback systems needed to deliver 'truly smart prosthetics and intelligent robotics'.

As well as the pain-sensing prototype, the research team said it has also developed devices using stretchable electronics that can sense and respond to changes in temperature and pressure.

With further development, the stretchable artificial skin could also be a future option for non-invasive skin grafts, where the traditional approach is not viable or not working.

"We need further development to integrate this technology into biomedical applications but the fundamentals - biocompatibility, skin-like stretchability - are already there," Bhaskaran said.

The new research, published in Advanced Intelligent Systems and filed as a provisional patent, combines stretchable electronics that incorporate oxide materials with biocompatible silicone to deliver transparent, unbreakable and wearable electronics; temperature-reactive coatings based on a material that transforms in response to heat; and electronic memory cells that imitate the way the brain uses long-term memory to recall and retain previous information.

The pressure sensor prototype combines stretchable electronics and long-term memory cells, the heat sensor brings together temperature-reactive coatings and memory, while the pain sensor integrates all three technologies.

PhD researcher Md Ataur Rahman said the memory cells in each electronic artificial skin prototype were responsible for triggering a response when the pressure, heat or pain reached a set threshold.

"We've essentially created the first electronic somatosensors - replicating the key features of the body's complex system of neurons, neural pathways and receptors that drive our perception of sensory stimuli," he said. “While some existing technologies have used electrical signals to mimic different levels of pain, these new devices can react to real mechanical pressure, temperature, and pain, and deliver the right electronic response.

"It means our artificial skin knows the difference between gently touching a pin with your finger or accidentally stabbing yourself with it - a critical distinction that has never been achieved before electronically."

The electronic artificial skin research was supported by the Australian Research Council and undertaken at RMIT's Micro Nano Research Facility.

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

Ground effect fans were banned from competitive motorsport from the end of the 1978 season following the introduction of Gordon Murray's Brabham...