Electrified ‘sponge’ material can absorb CO2 directly from the air

Researchers from Cambridge University have developed a low-cost and energy-efficient method for making materials that can capture carbon dioxide directly from the air.

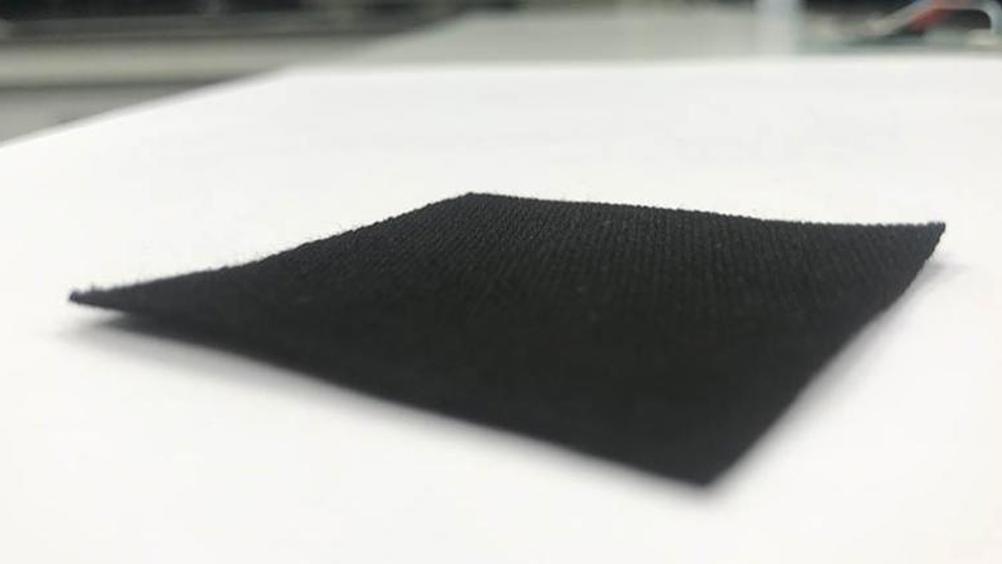

The method, which the researcher said is similar to charging a battery, charges activated charcoal often used in household water filters.

By charging the charcoal ‘sponge’ with ions that form reversible bonds with CO2, the researchers found the charged material could capture CO2 directly from the air.

“Capturing carbon emissions from the atmosphere is a last resort, but given the scale of the climate emergency, it’s something we need to investigate,” lead researcher Dr Alexander Forse from the Yusuf Hamied Department of Chemistry said in a statement.

“The first and most urgent thing we’ve got to do is reduce carbon emissions worldwide, but greenhouse gas removal is also thought to be necessary to achieve net zero emissions and limit the worst effects of climate change. Realistically, we’ve got to do everything we can.”

Direct air capture, which uses porous materials to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, is one potential approach for carbon capture, but the researchers said that current approaches are expensive, require high temperatures and the use of natural gas, and lack stability.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...