In a proof-of-principle study with mice, the bandage is said to have accelerated callus formation and vascularisation to achieve better bone repair by three weeks.

The research by a team at Duke University in North Carolina points toward a general method for improving bone repair after damage that could be applied to medical products including biodegradable bandages, implant coatings or bone grafts for critical defects. Their results are published in Advanced Materials.

Low-cost OCT scanner promises to save eyesight

Handheld probe images individual photoreceptors in infant eyes

In 2014, Shyni Varghese, professor of biomedical engineering, mechanical engineering and materials science, and orthopaedics at Duke, was studying how biomaterials made of calcium phosphate promote bone repair and regeneration. Her laboratory discovered that the biomolecule adenosine plays a particularly large role in spurring bone growth.

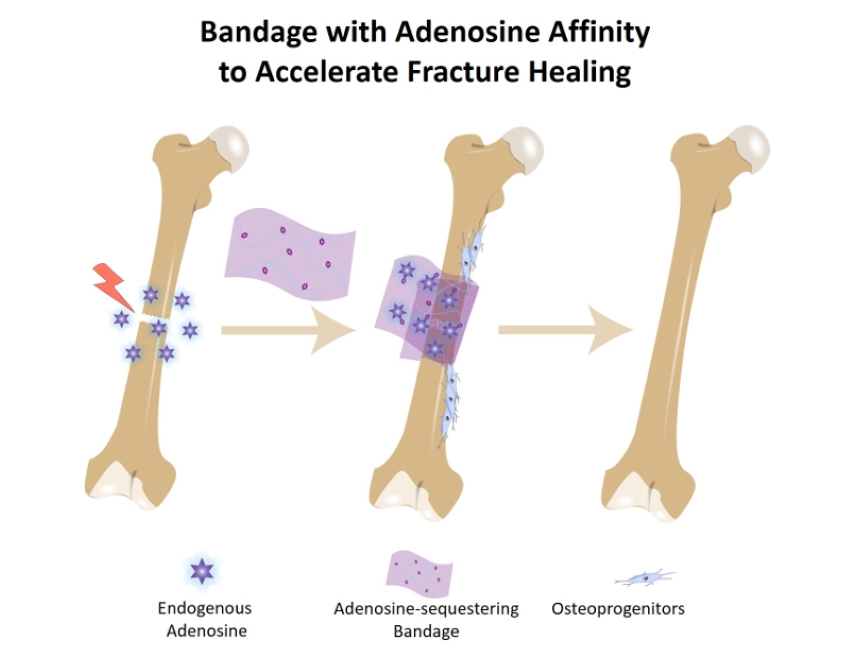

After further study, they found that the body naturally floods the area around a new bone injury with the pro-healing adenosine molecules, but those locally high levels are quickly metabolised.

"Adenosine is ubiquitous throughout the body in low levels and performs many important functions that have nothing to do with bone healing," Varghese said in a statement. "To avoid unwanted side effects, we had to find a way to keep the adenosine localised to the damaged tissue and at appropriate levels."

Varghese's solution was to let the body dictate the levels of adenosine while helping the biochemical remain around the injury a little bit longer. Varghese and graduate student Yuze Zeng, designed a biomaterial bandage applied directly to the broken bone that contains boronate molecules that sequester the adenosine. The bonds between the molecules are finite, allowing a slow release of adenosine from the bandage without accumulating elsewhere in the body.

Bone repair

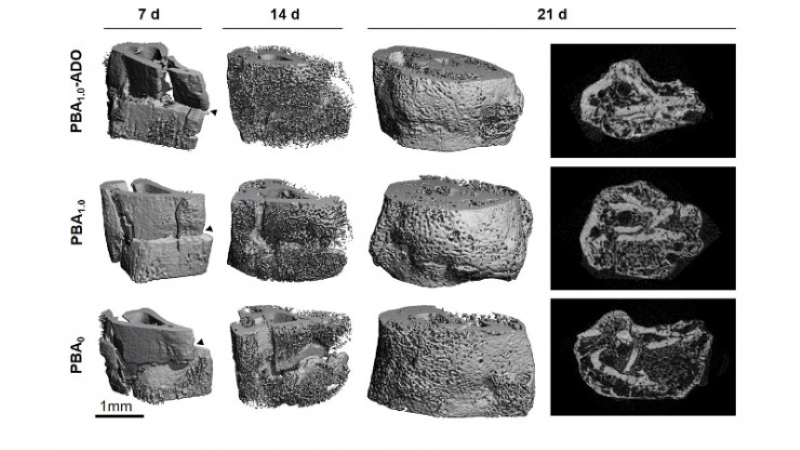

In the current study, Varghese and her colleagues first demonstrated that porous biomaterials incorporated with boronates could capture the local surge of adenosine following an injury. The researchers then applied bandages primed to capture the host's own adenosine or bandages preloaded with adenosine to tibia fractures in mice.

After more than a week, the mice treated with both types of bandages were healing faster than those with bandages not primed to capture adenosine. After three weeks, while all mice in the study showed healing, those treated with either kind of adenosine-laced bandage showed better bone formation, higher bone volume and better vascularisation.

According to Duke, the results showed that not only do the adenosine-trapping bandages promote healing, they work whether they're trapping native adenosine or are artificially loaded with it, which has implications in treating bone fractures associated with ageing and osteoporosis.

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

Ground effect fans were banned from competitive motorsport from the end of the 1978 season following the introduction of Gordon Murray's Brabham...