The audio enclaves, developed in research led by Yun Jing, professor of acoustics in the Penn State College of Engineering, are said to work in an enclosed space, like a vehicle, or standing directly in front of the audio source.

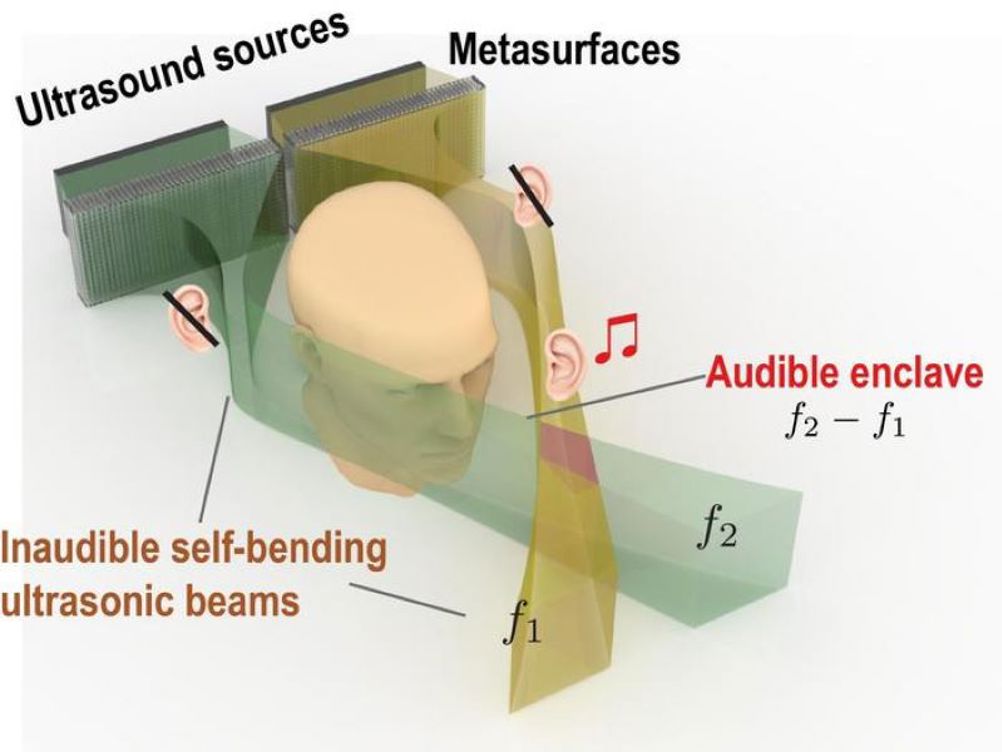

In their study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers explained how emitting two nonlinear ultrasonic beams creates audible enclaves, where sound can only be perceived at the precise intersection point of two ultrasonic beams.

“We use two ultrasound transducers paired with an acoustic metasurface, which emit self-bending beams that intersect at a certain point,” said corresponding author Jing. “The person standing at that point can hear sound, while anyone standing nearby would not. This creates a privacy barrier between people for private listening.”

By positioning the metasurfaces - acoustic lenses that incorporate millimetre or submillimetre-scale microstructures that bend the direction of sound - in front of the two transducers, the ultrasonic waves travel at two slightly different frequencies along a crescent-shaped trajectory until they intersect, the researchers explained. The metasurfaces were 3D printed by co-author Xiaoxing Xia, a staff scientist at the US Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore Laboratory.

According to the researchers, neither beam is audible by itself - it is the intersection of the beams that create a local nonlinear interaction, which generates audible sound. Furthermore, the beams can bypass obstacles to reach a designated point of intersection.

“To test the system, we used a simulated head and torso dummy with microphones inside its ears to mimic what a human being hears at points along the ultrasonic beam trajectory, as well as a third microphone to scan the area of intersection,” said first author Jia-Xin “Jay” Zhong, a postdoctoral scholar in acoustics at Penn State. “We confirmed that sound was not audible except at the point of intersection, which creates what we call an enclave.”

For now, researchers can remotely transfer sound about a metre away from the intended target at a volume of around 60 decibels. The researchers said that distance and volume may be able to be increased if they increased the ultrasound intensity.

Deep Heat: The new technologies taking geothermal energy to the next level

No. Not in the UK. The one location in the UK, with the prospect of delivering heat at around 150°C and a thermal-to-electrical efficiency of 10-12%,...