Low maintenance, quick to refuel, highly efficient, and zero-emissions at point of use - hydrogen fuel cells are, on the surface, something of a net zero no-brainer. But despite the technology’s potential to play a key role decarbonising a range of sectors, it’s yet to be deployed at anything like the scale required to make a meaningful impact.

There are a number of reasons for this: not least the often-discussed challenges around hydrogen infrastructure. But perhaps the biggest stumbling block is the fact that the business of actually making fuel cells is expensive. Whilst the EV battery sector has been able to lean on decades of volume manufacturing expertise, the hydrogen fuel cell - despite being invented in 1842 - has remained something of a niche technology, with the cost of the materials and the intricacies of the manufacturing process posing a major hindrance to commercialisation.

Now however, UK startup Bramble Energy believes it might just have come up with a solution that unlocks the technology’s potential: a fuel cell design that taps into the nimble and high-volume manufacturing capabilities of a sector responsible for one of the most ubiquitous components of the technological age: the printed circuit board.

The problem with the fuel cell stacks that exist is that all of them have to have a bespoke factory made to make them at scale, the concept behind Bramble is to use the PCB industry

Co-founded in 2016 by chemical engineer Dr Tom Mason and UCL’s Professor Dan Brett, Bramble’s core concept came from a 2010 Carbon Trust competition aimed at exploring methods of taking the cost of out of fuel cells. Today employing 85 full time staff, the firm has grown rapidly since its inception and last year moved to a swanky new HQ in Crawley, West Sussex dubbed the “Hydrogen Innovation Hub”.

Now, with a series of successful trials under its belt, the company is poised to announce its first commercial customer, a development that will mark a key step in its ultimate ambition to dominate the global fuel cell sector.

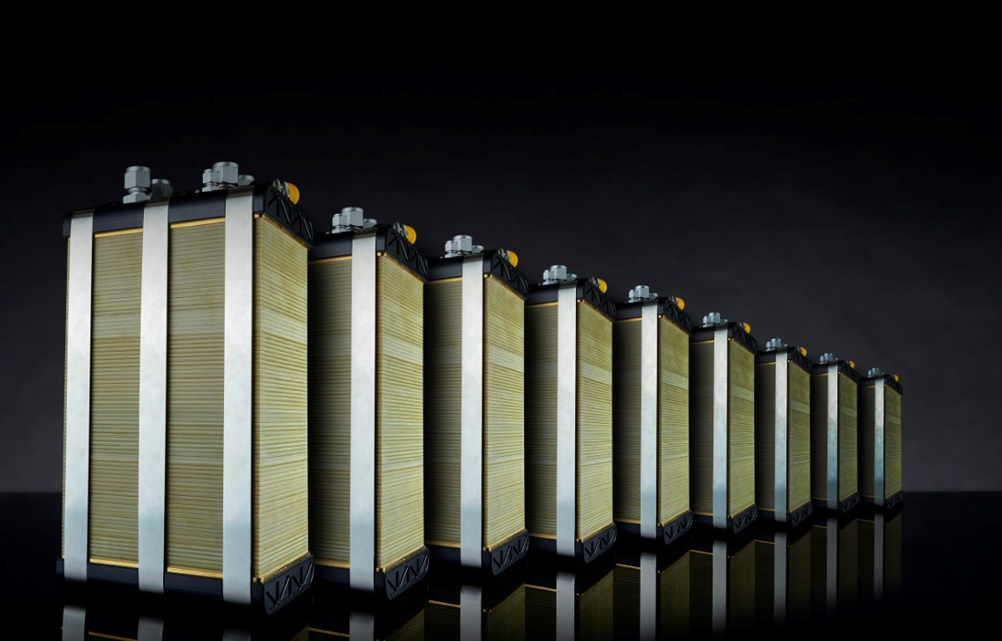

At a basic level, Bramble’s technology is not much different in operation to any other so-called PEM (Proton Exchange Membrane) fuel cell (see box out). The key innovations lie in the fact that Bramble’s fuel cell stack is effectively made from printed circuit boards (while conventional fuel cell stacks rely on stamped plates to hold the various layers) and also in the development of an innovative screen-printable carbon-based ink that protects the stack’s central component – the MEA (Membrane Electrode Assembly) - from the toxic effects of the copper in the PCB.

The key advantage of all of this is that the Bramble Printed Circuit Board Fuel Cell (PCBFC) can effectively be produced on existing PCB production lines anywhere in the world. The company’s model is to license the technology to the PCB manufacturers who already sit within the supply chains of most of its target customers (e.g.the large automotive OEMs). “The problem with the fuel cell stacks that exist is that all of them have to have a bespoke factory made to make them at scale,” explained Mason. “The purpose behind Bramble was to say how can we make those stacks without having to build a factory? And the concept was to use the PCB industry.”

It’s an approach that neatly circumvents the expense of manufacturing scale-up and which enables Bramble to tap into the high volume and flexible capabilities of a huge global manufacturing base, a situation that Mason believes could enable its technology to ultimately cost as little as $60/kW, which is more than ten times cheaper than current technologies.

The model has the added benefit of de-risking the technology for investors. “Some of our potential customers are people like Tata, and Tata isn’t going to rely for its engine supply on a pokey little company like Bramble!” said Mason. “But by having the mechanism where it’s a license to their manufacturing supply chain, all of the risk is controlled by the customer.”

Until now the company has been entirely funded by a mixture of venture capital and grant awards (to the tune of around £52 million) during which time it has produced a series of technology demonstrators including, most recently, a fuel cell powered canal boat equipped with a marinised version of the technology. The firm is also involved in the Advanced Propulsion Centre funded HEIDI project (Hydrogen Electric Integrated Drivetrain Initiative) a collaborative effort involving Aeristech, Eqiuipmake and Bath University aimed at the development of a hydrogen fuel-cell powered double-decker bus.

Meanwhile, solid commercial interest in the proposition is gathering momentum, and Mason told The Engineer that he expects to soon be able to announce the first commercial customer for the technology: a large US mobility OEM, for whom it has designed a 670kW fuel stack.

After that the Bramble Energy team hopes to quickly reach the “critical mass” of customers required to reach profitability. By current estimates, this should happen by 2027/ 2028, which Mason believes would be a remarkable achievement for such a young business in what’s proved a tough market to crack: “As a business, from conception through to profitability….we’ll have only had to raise about £60 million, which for a hardware company in this business is ridiculous!”

Ridiculous or not, it’s this relatively capital-lite model that has helped the company succeed in a sector littered with the corpses of abandoned enterprises. “Lots of fuel cell companies have died because they had to build factories,” said Mason. “If we came up with this approach but needed to build factories, Bramble wouldn’t work.”

Bramble’s approach is undoubtedly a compelling solution to some of the problems that have held back the growth of the fuel-cell sector. But whilst the company is well-placed to play a key role accelerating its growth in the years ahead, Mason is under no illusions about the challenges that lie ahead. “I don’t think this industry will be mature until mid-2030s at the earliest.” he said, “It’s about the scale of it. If you do a thousand buses that’s nothing until you’ve got it at the scale where it’s hundreds of thousands of vehicles. I don’t see it happening in any sort of volume before 2030…and it will take time to ramp up…the complexity of the value chain should not be underestimated.”

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

Ground effect fans were banned from competitive motorsport from the end of the 1978 season following the introduction of Gordon Murray's Brabham...