UAVs (Unmanned air vehicles) are now a regular feature of modern warfare. Widely used for reconnaissance, and increasingly deployed in an offensive capacity, the technology is developing fast — with engineers adding ever-increasing levels of autonomy and performance improvements that could soon put UAVs on a par with manned aircraft.

But while the current generation of UAVs are undoubtedly useful, armed forces around the world are increasingly talking of the need for smaller, more agile systems that can be easily transported and operated by troops on the ground.

Enter the world of the MAV (micro air vehicle), a fevered area of research that’s leading to the development of tiny unmanned air vehicles able to peer around corners, fly into buildings and generally keep troops out of harm’s way.

People can do things now that they couldn’t foresee even five to 10 years agoDr Stephen Prior

Engineers have been talking about MAVs or Nano Air Vehicles for more than decade, but recent improvements in batteries and other key electronic components mean that the technology is now becoming more practical and affordable.

‘People can do things now that they couldn’t foresee even five to 10 years ago,’ said Dr Stephen Prior, a UAV specialist from the University of Southampton. ‘Microprocessors are becoming cheaper, faster and more capable, and the technology from the remote-control world is starting to become pervasive and affordable.’

Perhaps the most striking example of this phenomenon in action is the Black Hornet (or PD100), a tiny surveillance helicopter that’s being used by British troops in Afghanistan.

Developed by Norwegian firm Prox Dynamics — which began life developing devices for the remote-control plane market — the tiny vehicle weighs just 15g and measures around 10 by 2.5cm. It was adopted by British forces following an urgent 2011 MoD call for a “Nano UAS” for use in Afghanistan.

Launched by hand and controlled via a tablet, the device is equipped with a tiny video camera and video downlink that it uses to relay real-time footage to its operators.

The British army has been using the device for about a year and it has reportedly gone down well with the troops. ‘It allows them to do things they couldn’t do before,’ said Prior. ‘If I was a grunt on the frontline and my platoon sergeant said “that house over there, we’re going to kick the door down and see who’s inside”, instead I could fly my UAV over the compound and have a look around first just to see if anyone’s waiting for me.’

Prior added that one of the compelling advantages over larger surveillance UAVs such as the Reaper is that the system can ‘be tasked in a matter of seconds’, whereas a reaper might take half an hour to arrive at the scene.

The diminutive devices aren’t cheap — the MoD paid £20m for 160 units — a price tag that prompted a predictably aghast reaction from some sections of the media, which lambasted the MoD for spending millions on a “toy”.

But Prox Dynamics’ CEO and founder Petter Muren told The Engineer that the technology that appears on the PD100 is considerably more advanced than anything that would be found on a remote-controlled aircraft. The motors, servos and sensors are, he said, smaller and more efficient. The radio-link is more advanced, the system has fully integrated GPS, as well an autopilot system, and is far more robust.

As you scale down, the air becomes thicker basically and it becomes much more of a challenge in terms of aerodynamic surfaces. The degree of complexity is multipliedDr Stephen Prior

Prior, who put forward his own quad-rotor UAV in response to the MOD’s call and has seen the Black Hornet in action, said that the vehicle represents a major step on from anything else that’s available. ‘It’s a world-beating system that even the Americans couldn’t compete with,’ he said. ‘Not only is it only 15g, if you think about what’s on board it’s got a full flight controller, a camera, a video downlink, a hub link to control it and it’s aerodynamically capable to operate in the real world in windy conditions ‘

Operating in real-world conditions — for an aircraft that weighs little more than AA battery — is no mean feat. Not only are the challenges of environmental conditions such as wind and dust magnified, but the aerodynamic challenges are quite different. ‘As you scale down, the air becomes thicker basically and it becomes much more of a challenge in terms of aerodynamic surfaces. The degree of complexity is multiplied,’ said Prior.

But while the Black Hornet is currently making a difference on the battlefield, research teams around the world are looking at a host of other technologies that are further away from deployment.

Some groups are working on similar helicopter-based technology to Prox Dynamics. Others, such as Prior’s team at Southampton, are developing slightly larger but extremely agile quad-rotor platforms. But some of the most intriguing research is taking its inspiration form nature, and looking into the development of flapping-wing vehicles that mimic bird and even insect flight.

The advantages of insect-type flight over other modes of operation are potentially huge. Flying insects are nature’s most accomplished aviators. Refined over 300 million years of evolution, their method is exceptionally power efficient, relatively silent and allows incredible feats of agility.

Mimicking this performance could, many believe, lead to a new generation of tiny air vehicles perfectly equipped to operate in confined cluttered spaces and potentially even inside buildings.

But the challenges are immense.

There are many impressive initiatives underway. Most recently, The Engineer reported on Harvard University’s RoboBee — an insect-sized robot, weighing less than a tenth of a gram, that was able to hover and fly along a preset route.

However, Cranfield University’s Professor Rafal Zbikowski — who until recently led UK efforts to replicate insect flight — said that the field now needs the backing of procurement agencies and companies with deep pockets in order to further develop the technology and move it out of the academic research laboratory.

‘There’s plenty of research being done,’ he said, ‘but what needs to happen now is to force the issue by procuring something. Black Hornet is a good example. Something similar needs to be done with flapping.’

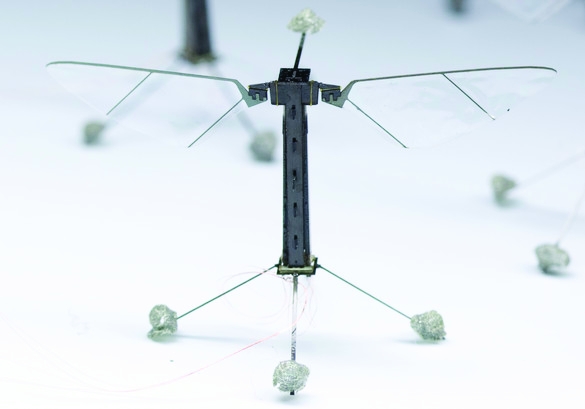

Perhaps one of the most significant moves in this direction is the nano-Hummingbird, a highly manoeuvrable flapping-wing vehicle unveiled in 2011 ago by US firm Aerovironment.

Developed with $4m funding from US defence research agency DARPA, the system mimics the insect-like flight of the hummingbird. With a wingspan of 16cm, it weighs just 19 grams (including flight systems, batteries, motors, communications systems and a video camera). The vehicle is able to fly in any direction and, critically, hover for up to 11 minutes.

But almost two years on from its maiden flight, Hummingbird is yet to be commercialised. And, although Aerovironment declined to comment, others have suggested that its performance is still a long way short of anything that would be operationally useful. ‘You have to ask why it hasn’t been commercialised,’ said Prior. ‘It doesn’t fly particularly well in wind gusts and it doesn’t have particularly great endurance.’

Another interesting innovation in the field — a flying robot dragonfly — recently emerged from the research department of German automation giant Festo. Unveiled earlier this spring, the Bionicopter has a wingspan of 63cm, a body length of 44cm and weighs 175 grams. Remotely operated via a smartphone, the robot is able to move each of its wings independently, which enables it to slow down, accelerate, turn abruptly and fly backwards.

Bionicopter has been developed primarily as a showcase for Festo’s expertise in function integration. However, it seems that in the process the company has cracked some pretty significant challenges: not least enabling its aircraft to hover on the spot, which is considered a key ability for an operationally useful MAV.

Explaining how it achieves this, a Festo spokesperson said: ‘The swivelling of the wings determines the thrust direction. The thrust intensity can be regulated using the amplitude controller. The combination of both enables the dragonfly to hover on the spot, manoeuvre backwards and transition smoothly from hovering to forward flight.’

Festo wouldn’t be drawn on whether it has even considered military applications for its technology, and with apparently little recent progress on hummingbird it seems we may have to wait a few more years for swarms of flapping-wing insect robots.

For many, that’s probably not such a bad thing. Because, while the use of larger UAVs is heavily regulated, there are growing concerns that smaller, lower-cost systems could be abused and used to invade people’s privacy.

‘It will be hard to control,’ said Prox Dynamics’ Muren, ‘but the industry should be careful with how and to whom they sell the technology. Prox Dynamics only sells to governments and all sales are carefully governed by Norwegian export control. We do not sell to any private or commercial customers.’

Prior agreed that this is a concern, but also warned against overly zealous regulation which, he said, could undermine the UK’s relatively healthy position in the sector.

‘In the US — where the FAA has clamped down on nearly every aspect of UAV work — there’s very little flying these days and, until they resolve the issue, the won’t have any new businesses. In Europe there’s a slightly healthier environment for testing technologies.’

Guest blog: exploring opportunities for hydrogen combustion engines

"We wouldn't need to pillage the environment for the rare metals for batteries, magnets, or catalisers". Batteries don't use rare...