The 20th century saw the mechanisation of transport, and warfare was the cradle and the laboratory for many vehicles. None of them, however, has become as potent a symbol as the tank. From its first appearance in the First World War, to the images of massed tank battles in the Second World War and beyond, the tank has become as much a metaphor for implacable military superiority as a force in itself. When prime minister Harold Wilson told a union chief in the 1970s to ’get your tanks off my lawn’, nobody doubted what he meant.

Conceived in the mid-19th century as a way of combining the functions of horse cavalry and mobile artillery pieces, the tank has had a familiar form and role since the 1940s – a lozenge-shaped body, protected by thick armour plate, running on tracked wheels and with a large gun on a rotating turret. They generally use large diesel engines, and the crew inside, although protected, have limited visibility, using periscopes or camera systems to see outside.

But the tank is changing. ’Tank design is about getting the right combination of protection, manoeuvrability and firepower; the Americans call it the “Iron Triangle”,’ said Hisham Awad, who heads up the Future Protected Vehicles (FPV) project at BAE Systems Global Combat’s Emerging Programme Unit. ’But we’re now coming to the limit of what can be done with that unless there are major advances in technology, such as improvements in railguns. That means that, to develop new protected vehicles, we have to take a conceptual leap sideways.’

When prime minister Harold Wilson told a union chief in the 1970s to ’get your tanks off my lawn’, nobody doubted what he meant.

BAE’s FPV project is, in part, a reaction to the Ministry of Defence’s (MoD) ’Capability Vision’ for armoured vehicles, designed to spur development along different paths from the MoD’s previous research. The ministry’s goal for FPVs – aiming for a prototype within four years and an experimental operational capacity by 2013 – is for a lightweight vehicle, weighing 30 tonnes, powered by a hybrid electric drive, with the same effectiveness and survivability of a current main battle tank (MBT). The UK’s current MBT, the Challenger 2, weighs 62.5 tonnes, and runs a 1,200hp V12 diesel engine. But for tank makers, the view goes even further. ’We look at three different timescales,’ Awad said. ’One is what’s needed right now in theatre. The second is what’s achievable in five, 10 or 15 years. Some of the other things are much longer term, looking at 50 years hence.’

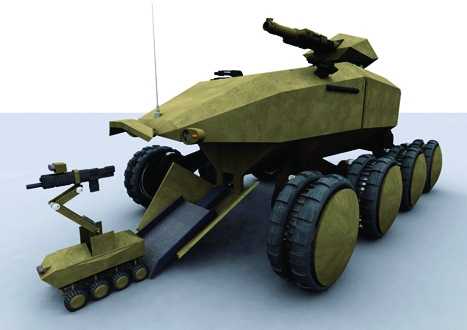

It’s a given that the raison d’etre for a tank will always be to carry a large gun (or other suitable-sized equipment), but its other main task – to protect the troops inside – could change dramatically, with implications for the kind of protection it needs and for the way that it moves. ’Protecting humans has always been a big design driver, and we accept that you’ll always need soldiers [inside tanks],’ Awad said. ’But you won’t need as many soldiers in there. That means that you can change the philosophy from protecting people to protecting technology that can be repaired or interchanged. You would no longer need to think about 10-15 people in the back of the tank. You could have one or two; you could even have none. That dramatically reduces the size of the vehicle.’

One contributing factor here is the development of new materials that can be used to armour the tank, particularly ceramics and composites. ’There have been big developments with ceramics, and they are no longer kept out of our industry by their cost,’ Awad said. ’These are materials that exist; we’ve done the physics work on them and we know their limits, but now we need to do work to show how they’ll behave in an example environment.’

“We’re coming to the limit of what can be done with what Americans call ’The Iron Triangle’ of firepower, manoeuvrability and protection. To develop new vehicles, we have to take a conceptual leap sideways”

Hisham Awad, BAE Systems

Transparent armour has particularly exciting possibilities, and transparent ceramics are already showing great promise in this area. Transparent alumina – made by subjecting sub-micron-sized grains of aluminium oxide (Al2O3), the same compound that comprises sapphire and ruby, to high temperature and pressure – was developed at the Fraunhofer Institute for Ceramic Technologies and Sintered Materials in 2003, and is lighter and stronger than steel. Other transparent ceramic armour candidates include aluminium oxynitride spinel, which is being developed by Raytheon; the company has succeeded in making a window from the material measuring 11in2.

For a tank designer, transparent ceramics would represent a major change. Previous types of armoured glass have not been strong enough to use as windows in a fully-armoured vehicle. Crews can use remote cameras to provide a view of the outside world, which keeps them safe, but at a penalty: it reduces spatial awareness, dislocating the crew from their natural feel of their position within the environment. ’Having armoured materials that you can see through gives you a big advantage here,’ Awad said.

Another advantage of ceramic armour is its weight; using this material rather than steel would make a tank a far lighter and nimbler vehicle than the lumbering behemoths we’re used to seeing. The sheer mass of a conventional tank has its advantages, especially when it comes to protection against mines. The sort of explosion that generates the equivalent force of 200g in a fraction of a second is very hard to protect against; current strategies include seats that are designed to absorb heavy impacts, which work in a similar way to aircraft ejector seats. ’But the benefits to manoeuvrability of lighter, stronger materials far outweigh the benefits of mass,’ Awad said. ’We would like to make them as light as possible.’

Nimbler vehicles will likely mean a different system for moving the tank around. Could it be goodbye to tracks? Many in the industry believe that electric drive could spell the end for the most recognisable feature of tanks, with hub-mounted motors equipped with anti-slip devices providing more traction than tracks.

It’s an often-heard observation that military engineers design for the last war, and it’s true that tracked vehicles have been very well suited for massed battles in muddy fields. But they are less suited to other terrains and designers are keen to avoid limiting the types of environment that their vehicles can operate in. Some of the possibilities have the distinct taste of science fiction around them. Awad said: ’There’s always been an argument between wheels and tracks, but it’s not all about that now; there are hybrid systems, hovercraft, even walker systems. When we’re looking at future technologies, up to 50 years ahead, we’re opening the door to new ideas.’

Devotees of The Empire Strikes Back will be particularly amused by Awad’s talk of walkers, but he is adamant that it’s a valid idea for speculative development. ’We have a couple of concepts of walking systems, simply because it’s much easier to walk rather than drive over hard terrain. You can walk up Mount Everest but you certainly can’t drive up it. Apply that logic to an armoured vehicle, and there are certainly ideas that could justify walker vehicles.’

There’s always been an argument between wheels and tracks, but it’s not all about that now; there are hybrid systems, hovercraft, even walker systems.

Hisham Awad, BAE Systems

The future, however, is likely to be modular. With the FRES vehicles leading the way (see box; BAE Systems’ bid, like General Dynamics’, was a modular system), armies are likely to have the choice of fitting an armoured body with whichever weaponry and mobility system suits the particular mission best. Half-tracks, full-wheel and walking hybrid systems could all be available. With electric drive and other software-based electronic systems onboard, future tanks will have a far greater demand for electricity than current vehicles. This is likely to mean a further shift in the role of tanks. As well as being a method of moving weaponry and troops around, they could become a way of moving electricity, as the power system inside the tank shifts from providing torque to drive it, to generating power for its systems.

One example of a possible future system is under test by BAE Systems Land Systems Hagglunds in Sweden, with a modular armoured system known as SEP. This has an electric transmission system, six wheels driven by electric motors, and two engines providing the power. It can be run silently off batteries, which are charged by the engines. The SEP is designed on a modular basis, which allows it to be reconfigured for 24 different roles, including anti-tank missile system, mine clearer and NBC decontamination centre. SEP is not currently deployed by any armed forces: Sweden cancelled its SEP programme in 2008 because it could not find international collaborative partners.

Awad believes that diesel engines are likely to provide the power source for some time yet. ’We haven’t reached the limit of what can be done in the mechanical diesel arena, but there will be a limit. Beyond that, we might look at nuclear power generators, which are currently too big, but we’ve always been good at making things smaller. In the far future, we might design a reactor for 10 years’ service, which is the operational life of the platform; it would never need refuelling or maintenance, and it would be sealed with an exotic material that would provide shielding.’

So, if we look far enough into the future, could we see walking, nuclear-powered tanks with synthetic sapphire windows, running plug-in software with modular weapons packs? ’Really, the only limit is our imaginations: whatever technology best fits the mission profiles,’ Awad said. Whether you would find a soldier willing to crew one might be another matter.

Indepth

Suit of armour

The next generation of British Army tanks will be manufactured predominantly in the UK

The FRES generation

The next generation of tanks to enter service in the British Army are in the FRES (Future Rapid Effect System) group, and after a contentious and acrimonious bidding process, they will be built by General Dynamics.

Classified as a light tank rather than the heavier MBT class, the FRES vehicles are designed to fill scouting and specialist roles. General Dynamics’ ASCOD SV (specialist vehicle) is rated at up to 42 tonnes, which, according to chief engineer John Abunassar, means it can carry a 120mm gun without compromising its armour or performance.

The turret ring on the vehicle is 1.7m wide, with the main ammunition feed under armour but outside the turret crew compartment. This allows space for display screens inside the turret while still allowing some freedom of movement for the crew, even if they are wearing body armour. ’Our design for a large turret ring is an advantage for the soldiers inside,’ Abunassar said.

The ASCOD family was developed by the Austrian and Spanish subsidiaries of General Dynamics in the late 1990s; the first version entered service in 2002. To meet the MoD’s brief, the UK subsidiary refined the design and came up with four variants: the scout, the command post and forward reconnaissance armoured vehicles, and an armoured recovery vehicle. The turret was designed by Lockheed Martin UK, which will also produce the component.

Manufacturing will be based in the UK, the company said. Eighty per cent of the manufacture will be completed in the UK, with 70 per cent of the supply chain made up of UK-based companies. The MoD’s initial order is for 580 vehicles.

From the archive

Memory tanks

From horse to tank, as reported in The Engineer in January 1856

The object of this invention is to render the attack of cavalry more formidable than hitherto, by providing horses with a means of destroying troops against which the attack is directed. For this purpose, it is proposed to surround the horse with a rigid frame or shield… which frame is supported by the hame of the horse collar. Attached to this frame or shield (which forms a defensive armour to the horse and the lower extremities of the rider) are cutting edges, which are capable of being adjusted to act as offensive weapons during the attack, and of being returned to an innocuous position when not required for action.

Radio wave weapon knocks out drone swarms

Probably. A radio-controlled drone cannot be completely shielded to RF, else you´d lose the ability to control it. The fibre optical cable removes...