For more than half a century Honda has been the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer. The latest figures say that by the end of 2019, the Japanese conglomerate had made more than 400 million of them. Honda also makes more than 14 million internal combustion engines per year, is Japan’s second largest automobile producer, and is consistently in the global top ten car manufacturers. In 2016, its 100 millionth car rolled off the production line. With a market capitalisation of $150bn, Honda is one of the biggest names in the personal transportation sector. It all started in a bicycle repair shack near Mount Fuji.

The man who gives his name to one of Japan’s most recognised brands – Soichiro Honda – was born in the village of Kōmyō, near Hamamatsu, in 1906. The son of a blacksmith and a weaver, he had neither the opportunity nor inclination for a formal education. One of the few clues to his engineering ingenuity to emerge from his childhood is the oft-repeated anecdote of how the young Soichiro forged his family seal in order to trick the authorities into believing that his parents had read and approved the contents of his school report. This he did by creating a stamp cut out of a rubber bicycle pedal cover. While he succeeded in the original deception for his own documents, Honda was eventually exposed when he applied the same ruse to help out his schoolmates. As a counter-forgery measure, the authorities required family seals of approval to be provided in mirror image. But, because his family name is symmetrical when written in Japanese characters, the deception was not immediately apparent, but was soon spotted when he started to produce seals for other children.

Perhaps a more clear-cut indication of his early predilection for engineering is that later in life Honda would reminisce on the sight of the first car that came to his village, or the smell of the oil that it gave off. According to his biographer David Tremayne in Soichiro Honda: The Man Behind the Legend, the youngster also stole a bicycle from his father’s workshop to attend a flight demonstration by the American pilot Art Smith. Tremayne records how, when the theft was brought to his attention, Honda senior was more impressed with his son’s initiative than he was angry with him for taking the money and the bike.

At the age of 15 Honda saw an advertisement in Bicycle World magazine for an automobile servicing company by the name of Tokyo Art Shokai. Although not a recruitment notice, it was attractive enough for Honda to write speculatively touting for employment.

His application successful, Honda soon found himself bound for the bright lights of Tokyo. The owner of Art Shokai, Yuzo Sakakibara, identified the young apprentice’s potential and began to take close notice of him. Meanwhile, Honda was learning from his boss not just the engineering aspects of processes such as piston design, but how to deal with customers as well. When asked who the greatest influence on him had been, Honda would for the rest of his career cite Sakakibara as the ideal teacher.

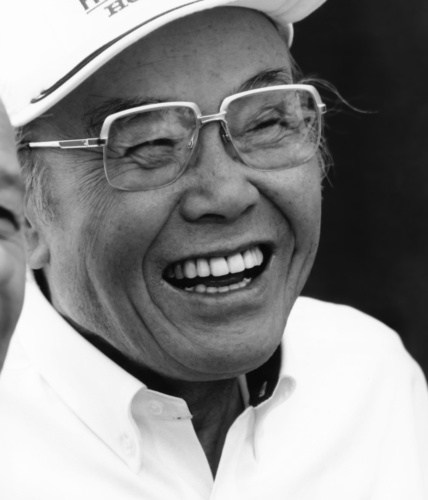

Success can only be achieved through repeated failure and introspection

Soichiro Honda (1906 - 1991)

By April 1928, Honda had completed his apprenticeship and had returned home to open a branch of Art Shokai in nearby Hamamatsu. Honda was the only one of Sakakibara’s trainees to be granted such a level of independence. During this formative phase of his career, Honda earned the nickname ‘Edison of Hamamatsu’ due to his high levels of creativity and innovation. By 1935 the facility at Hamamatsu had more than 30 employees on the books. Encouraged by Sakakibara, during this time Honda developed a lifelong interest in motor racing, although his career as a driver was to be cut short after an accident behind the wheel of the ‘Hamamatsu’ in the ‘1st Japan Automobile Race’ at the Tamagawa Speedway in 1936. Honda explained his retirement thus: “When my wife cried and begged me to stop, I had to give it up!” His wife counter-claimed that Honda hung up his driving gloves after a stern lecture delivered by his father.

In 1937, Honda founded Tōkai Seiki to produce piston rings for Toyota. After a shaky start, in which early output had as low as six percent quality standard success rates, Honda spent two years visiting universities and steelmaking companies all over Japan in order to study manufacturing techniques. Finally in a position to supply reliable mass-produced parts to companies such as Toyota and Nakajima Aircraft, at the height of the company’s success, he employed more than 2,000 people. But the success was to be short lived. During the Second World War, Honda’s facility at Hamamatsu was reduced to rubble by enemy air bombardment. Further disaster followed in the form of the Nankai earthquake in 1945, the same year that Japan formally surrendered to the Allies, bringing an end to the war.

In post-war Japan, under the banner of the newly formed Honda Technical Research Institute (funded by the sale of the remains of the Hamamatsu plant), Honda responded to the challenge of getting the nation mobile again by retrofitting surplus generator motors to bicycles. The next challenge was to produce ‘motorised bicycles’ at a rate that could meet demand, and by 1947 the Honda-designed unit was being mass-assembled on its own conveyor. The following year Honda brought in a professional managing director –Takeo Fujisawa – and the Honda Motor Company was formed. By the close of the decade, the first fully-fledged motorcycle designed in its entirety by Honda – the air-cooled, two-stroke, single-cylinder engine ‘Dream’ D-Type – was a market favourite. Its success was not without an element of irony, as sales were boosted by the US military’s special procurement purchases on the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950.

By 1955 Honda was the biggest motorcycle brand in Japan and by the end of the decade had opened its first dealership in the United States. This marked the company’s adoption of the emerging commercial concept of thinking globally, summed up in one of its official mission statements as committing to “supplying products of the highest quality yet at a reasonable price for worldwide customer satisfaction.” At the same time Honda introduced the Super Cub four-stroke motorcycle that in its various incarnations has been in continuous production ever since. The new motorcycle’s advertising campaign slogan – You meet the nicest people on a Honda – was to have a profound and positive effect on Honda’s image and on American attitudes to motorcycling, becoming the focus of countless business marketing studies. By 1960, Honda had emerged as a billion-dollar multinational that produced the best-selling motorcycles in the world, outselling even Triumph and Harley-Davidson in their home markets.

Landmark successes followed swiftly and frequently in the years leading up to Honda’s retirement from the business in 1973, with highlights including the introduction of the company’s first four-wheeled products in 1963 in the form of the T360 mini-truck and the S500 sports car. In 1964 Honda took its first steps into the motor racing arena, with American driver Richie Ginther recording Honda’s maiden Formula One Grand Prix victory in Mexico only a year later. In 1972 the Civic became the compact passenger car of its generation, eventually going on to sell more than 14 million units. This was to be the last major timeline event before both Honda and Fujisawa commemorated a quarter of a century at the helm by handing over to a new generation of management – with Kiyoshi Kawashima stepping in as president – before taking their seats on the board in an advisory role.

Following his retirement, Honda stayed actively involved in the company as the mystique surrounding him grew. In 1980 People magazine proclaimed him the ‘Japanese Henry Ford’, although history does not record how much of an honour he regarded the distinctly back-handed compliment. More fitting perhaps was that three years later his own company would anoint him ‘supreme advisor.’

Soichiro Honda died on 5th August 1991, less than a week before the Hungarian Grand Prix which was won by one of the greatest drivers in the history of the sport: Ayrton Senna. Driving to victory in his McLaren-Honda, Senna was to dedicate his victory to the memory of a true legend of the 20th century world of automotive design and manufacture.

Celebrate engineering's pioneers and ground-breakers

The Institution of Engineering & Technology (The IET) - sponsor of The Engineer's Late Great Engineers feature - is celebrating some of the incredible people who have made an impact in engineering and technology. Let the institution know who you think has made a difference by nominating a pioneer or groundbreaker today:

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

What a fun demonstration. I wonder if they were brave enough to be in the car when it was first turned over. Racing fan cars would be an interesting...