Shortly after David McMurtry died in late 2024 Money Week published a feature reflecting on the legacy of the billionaire engineer. It detailed how the Renishaw founder had created one of the great ‘success stories’ in twentieth century UK manufacturing as well as noting his vast personal wealth. But it also paid tribute to a man who distrusted investors, who preferred to be a voice for his stakeholders rather than shareholders. For McMurtry was a man who believed in manufacturing excellence, who cared less for lining the pockets of faceless City organisations and more for his employees and customers. ‘There will never be another David McMurtry’ concludes the feature writer. He was not alone in thinking so.

McMurtry’s obituary in the Guardian spoke of how he ‘did much to advance the scientific study of measurement – metrology – and so facilitated hi-tech mass production in many fields’, as well as drawing attention to how the one-time CEO of Renishaw and latterly chairman had been ‘a brilliant engineer... He was responsible for 47 patents at Rolls-Royce and went on to be named on over 200 patents for Renishaw innovations.’ A statement from his side-project McMurtry Automotive paid tribute to a six-decade career that embraced ‘creating future technologies, innovating across sectors and mentoring future generations’. Writing in Business West, his acquaintance Ian Mean suggested that the publicity-shy McMurtry was ‘the most prolific living inventor in Britain. He would never admit to that, of course.’ The company most associated with his name stated: ‘The manufacturing industry has lost a great innovator and many at Renishaw have lost a father figure and a friend.’

Pushing boundaries using novel engineering has driven me throughout life

Sir David McMurtry (1940-2024)

Born in Dublin’s coastal suburb of Clontarf in Ireland in 1940, David Roberts McMurtry was educated locally at Mountjoy School which he would later boast of for distinctly un-technological reasons: ‘my claim to fame is it was the school that the rock group U2 went to.’ By the time he was 18 years old he was apprenticed to the Bristol Aeroplane Company which was acquired by Rolls-Royce Holdings. Two decades later he was Chief of Concorde Engine Design at Rolls Royce, where McMurtry invented what was to become Renishaw’s first product. The touch-trigger probe, says the Renishaw website, ‘was invented by Sir David to solve a specific inspection requirement for the Olympus engines used in Concorde. This innovative product led to a revolution in three-dimensional co-ordinate measurement, enabling the accurate measurement of machined components and finished assemblies.’

The origin of the McMurtry’s touch probe is a classic parable of how innovation comes from necessity. While working on the Olympus engine McMurtry was to become increasingly frustrated with the unreliability of the existing co-ordinate measuring machines (CMMs) in use at Rolls-Royce. Taking matters into his own hands, he spent a weekend in his garage working on the problem and returned to work with a modified probe better suited to the task. The Guardian notes: ‘This key invention… led to a revolution in the measurement of complex three-dimensional objects. The resulting advance in manufacturing technology provided a secure funding stream for a host of allied technologies that underscore the role of precise measurement in our increasingly technological world.’

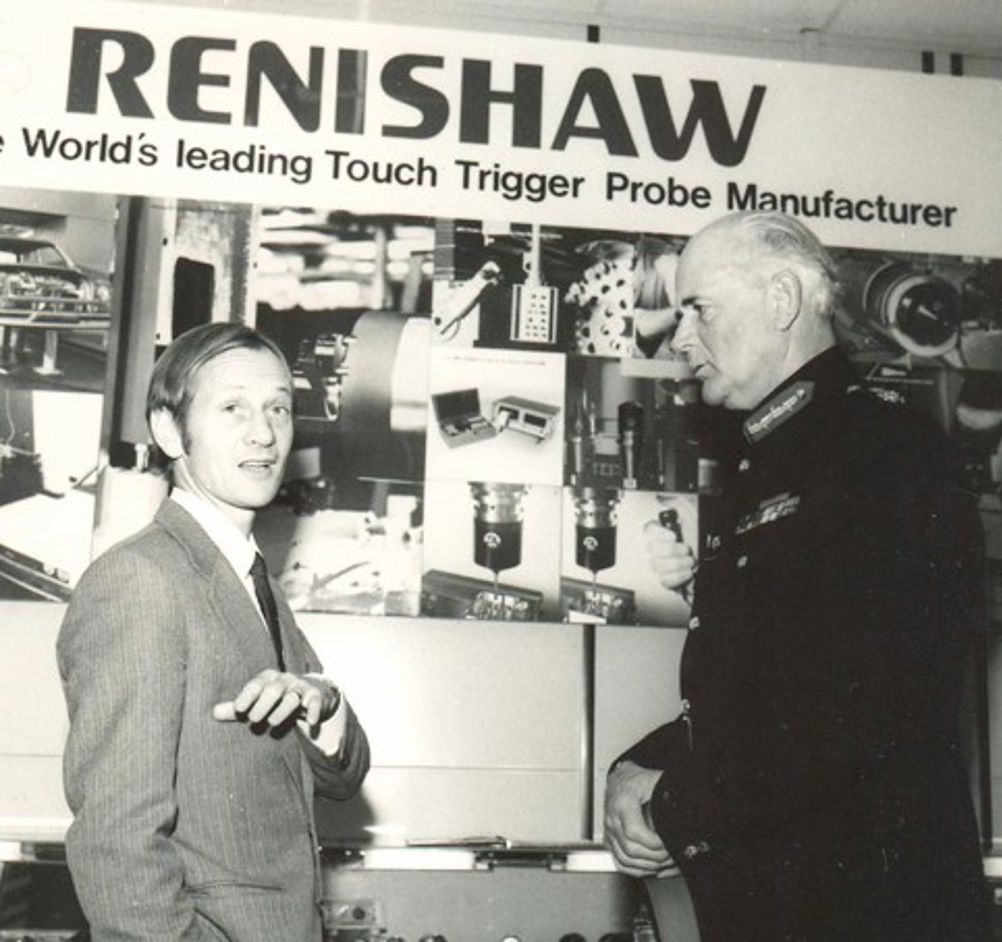

Once it had become clear to McMurtry that ‘there was money to be made from the sale of probes … I had to decide then to see how to get it into production. I met John Deer, a colleague at Rolls-Royce, and he seemed very keen on the idea. So we decided then that we’d start up a company between us’. The two engineers founded Renishaw in 1973 with the specific intention of commercialising the probe for use in CMMs. In this enterprise the engineering duo was successful beyond all doubt. As the Renishaw website states: ‘Today it is hard to imagine a machine shop of any size without tool setting and inspection probes that automate laborious and complex setting and measurement tasks. Yet in the 1970s, ideas for such applications were truly visionary’.

But they also wanted to create a company with a different culture to that which pervaded the British industrial ecosystem at the time. While the business itself made great strides in the areas of CMMs, shopfloor metrology and process control, it also placed a premium on integrity-related corporate philosophies such as the application of technology to solving real world problems, the preference for on-site manufacturing over outsourcing, and investment for the long-term benefit of its employees and customers rather than short-term returns for shareholders. Today, half a century after its founding, Renishaw employs 5,000 people in 36 countries and still prides itself on taking decisions ‘for the right reasons’.

Aside from his career in manufacturing McMurtry also became a figure in the world of electric sports cars. In 2016 he registered his eponymous startup company as an outlet for his instinct for ‘pushing boundaries using novel engineering’ in the automotive sector. The resulting Spéirling PURE electric single-seater hypercar made its debut at the 2021 Goodwood Festival of Speed where it was driven by five-time Le Mans 24 winner Derek Bell. The following year the Spéirling achieved a new Goodwood Festival of Speed hill climb record, completing the 1.87-kilometre (1.16 mi) course in 39.08 seconds with McMurtry test driver Max Chilton behind the wheel.

Commenting on both his Hypercar and the man himself (who in keeping with his general air of modesty drove a Volkswagen in everyday life) Top Gear noted: ‘An engineer to the core, he came into the automotive business relatively late in life. The remarkable Spéirling was initially born out of a desire to drive something small, sporty and nippy on the roads around his Gloucestershire home. But the project snowballed into the deeply radical fan assisted single seater that’s the fastest car ever up Goodwood’s hill.’ McMurtry was delighted with the record, calling it ‘just the beginning. Our vehicles have the power to transform not only track driving but also the wider motorsport and automotive landscape. Our customers share this vision and will soon become custodians of these era-defining vehicles.’ These customers it seems will need deep pockets. The Spéirling starts at around £820,000.

McMurtry was also to push his engineering creativity in another direction with the creation of his so-called ‘millennium mansion’ in Gloucestershire, Swinhay House. According to some estimates McMurtry’s futuristic development that covers 230 acres (93 hectares) of greenfield and forest near Wooton-under-Edge has a market value of £30m. And yet for all the hype that surrounded his ‘home’ being taken over as a film-set for the finale of the BBC series Sherlock, McMurtry never used it as a principal residence (he’s on record as saying his wife thought it was ‘too flashy’). Instead, the purpose of the building granted planning permission on the basis of its exceptional architectural and landscape interest – apart from acting as a demonstrator for sustainable technologies – was to be a venue for fund-raising events hosted by the engineer (who also donated the fee from Sherlock to charity).

Despite everything he achieved, McMurtry was, according to a statement released by Renishaw, ‘a reserved man who avoided publicity, and who was more comfortable sharing his insights with young engineers than making public speeches.’ The tribute goes on to explain that McMurtry amassed worldwide recognition, including in Japan and the USA, where he received honours historically reserved for citizens of those countries. In the UK, his knighthood was awarded ‘for services to Design and Innovation’, and he was appointed a Royal Designer for Industry (RDI) in 1989. He was also a Fellow of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, the American Society of Manufacturing Engineers, the Royal Academy of Engineering and of the Royal Society. In 2019, the IMechE awarded McMurtry the James Watt International Gold Medal for his outstanding contribution to mechanical engineering; the highest award the industry can bestow.

Perhaps the strongest indicator of McMurtry’s influence is that in 2008 he was honoured by the US Society of Manufacturing Engineers as a ‘Master of Manufacturing’; the first non-American to be recognised in such a way. In his citation, editor of Manufacturing Engineering Brian J Hogan explains that none of technology we see in today’s manufacturing world ‘simply emerged from primeval ooze. All of it is the product of the mind and imagination of some individual who worked in manufacturing, encountered a problem, and devised a solution to that problem. It’s safe to predict that David McMurtry’s touch probe will be used by manufacturing engineers at least throughout the twenty-first century. Persons who imagine manufacturing to be a dead end should consider McMurtry’s career.’

David McMurtry, one of the great twentieth century engineers, died in December 2024.

More from The Engineer

Deep Heat: The new technologies taking geothermal energy to the next level

No. Not in the UK. The one location in the UK, with the prospect of delivering heat at around 150°C and a thermal-to-electrical efficiency of 10-12%,...