Throughout the history of the discipline there have been few professional engineers that can lay claim to being a mainstream literary figure, while an equally small number have risen to the status of genuine household celebrity for reasons other than their engineering achievements. But Nevil Shute Norway – better known to the filmgoing and novel-reading public simply as Nevil Shute – was both. The world may have forgotten that he was at one time Chief Engineer on His Majesty’s Airship R100 having worked under Sir Barnes Wallis (of bouncing bomb renown). But it will be a long time before his seminal A Town Like Alice and On the Beach – along with the classic movies based on them – are forgotten. At one point Shute was the best-selling novelist writing in English. All 25 of his books remain in print.

While immensely popular with readers the world over, Shute’s novels were often shunned by a literary establishment that in the 1950s – Shute’s defining creative period – gave more critical attention to the likes of William Golding, Graham Greene and even J.R.R Tolkien. Shute’s works were more pedestrian – the author himself described his characters as ‘ordinary people doing extraordinary things’ – and his values were resolutely middle class. One of his prevailing themes was how sturdy professionals (such as himself) contributed more to society than the aristocracy or the ruling elite. He explored the dignity of labour, social integrity and the importance of science and technology. His 1954 autobiography Slide Rule concentrates more on his work as an engineer than on his publishing career. And if the frequency with which he used the expression is an indicator of his faith in it, he certainly believed that an engineer ‘can do for ten shillings what any fool can do for a pound’.

It has been said that an engineer is a man who can do for ten shillings what any fool can do for a pound; if that be so, we were certainly engineers

Nevil Shute (1899-1960)

Nevil Shute Norway was born in Ealing, Middlesex in 1899 to parents who we prosperous enough to send him to both the Dragon School in Oxford and then Shrewsbury School. A product of the preparatory and public education system, he progressed to the University of Oxford where he read engineering science at Balliol College. As John C Anderson comments in his 2003 address to the Nevil Shute Foundation: ‘In those days engineering was treated as one; there were no divisions such as mechanical, electrical or civil engineering as there are today’. As outlined in the university syllabus of the time, Shute would have studied mathematics, mechanics, structures, strength of materials, plus chemistry and surveying.

His father Arthur was a civil servant and minor author of such works as Highways and Byways in Devon and Cornwall and a history of the Post Office, knowledge of which he would have gained while serving as the English Secretary of the Irish Post Office in Dublin until the Easter Rising in 1916. His maternal grandmother Georgina Shute was a prolific nineteenth century novelist writing under the name George Norway. Shute remarks in Slide Rule that there wasn’t ‘a great deal in the theory that writing ability is dictated by heredity, but I think there is a great deal in environment. My father and my grandmother both wrote a number of books, so that the business was familiar to me before I started.’

While at university Shute took advantage of vacation work with aviation manufacturer de Havilland where, according to Anderson, he obtained a ‘good grounding in practical aspects of engineering… [and] would also have learned from aircraft designers – how things took shape on a drawing board and how designs were translated from drawings to reality’ He would also have witnessed the financial and management aspects of the aviation industry ‘that were to stand him in good stead when he later formed Airspeed’. Around this time Shute attended the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, where he trained as a gunner but was unable to follow his preferred trajectory into the Royal Flying Corps, probably due to his stammer. He served in the First World War as a soldier in the Suffolk Regiment instead.

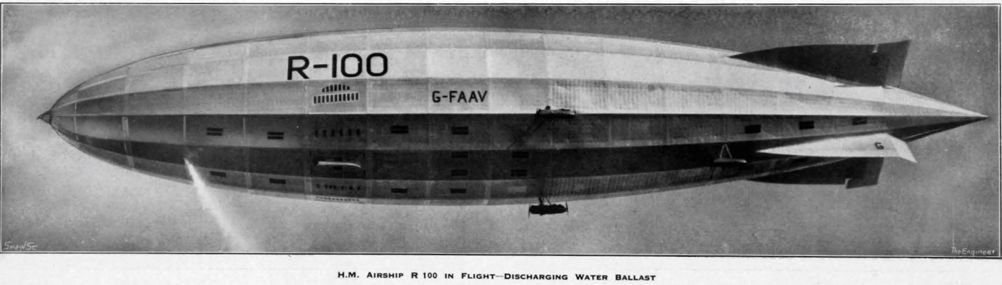

By 1924 Shute had cut ties with de Havilland and had taken a position at Vickers where he worked on airship development as Chief Calculator (stress engineer) on the R100, eventually rising to Chief Engineer under the name of Norway in order to deflect the publicity his fame was attracting. As Shute describes in Slide Rule, the R100 was a government-funded but privately developed prototype intended as a response to the highly successful German Zeppelin rigid airships, and which would go into service on British Empire routes.

Shute’s profile on the heritage section of the BAE Systems website goes into detail about the R100, stating that the ‘huge project’ was completed in 1929, with its December 1930 maiden flight taking place ‘on a calm day, without any wind. This was vital in order to get the airship out of the hangar as there was only around two feet clearance on each side of the craft’. After further flight trials the R100 undertook an intercontinental flight to Canada, taking 78 hours to complete the crossing to Montreal: ‘This meant that the R100 had set an average speed of 40 mph, over twice the speed of any existing ship or train journey’.

Three months later the R100’s sister airship R101 – which Shute believed had been rushed into operation – crashed in France during a long-distance trial flight to India. Forty-six passengers were killed, and along with them Britain’s ambitions to produce further airships. After the disaster Shute ‘was said to have been overly critical of the design of the R100 and the Vickers management team’ which meant that the airship workforce found themselves out of work, with the newly married Shute making frantic attempts to get his entire design team hired elsewhere. When this strategy failed Shute announced his intention to start his own aircraft manufacturing company Airspeed. Joining forces with former de Havilland designer Hessell Tiltman, and with investment from Sir Alan Cobham and a solicitor by the name of Hewitt, the directorial board was put in place with Lord Grimthorpe as its first chairman. Hopelessly underfunded – Airspeed started off with just £2,000 capital, and with its flotation raising less than £5,000 – Cobham came to the rescue, ordering two 10-seaters to be paid for out of his own pocket. Such were the demands of the business that ‘Nevil Shute’ went on six-year hiatus so that ‘Nevil Norway’ could devote his energy to Airspeed.

Despite its shaky start Airspeed slowly made progress, eventually gaining recognition when its Envoy aircraft was chosen for the King’s Flight. During the Second World War its AS.10 Oxford (the ‘Ox-box’) twin-engine monoplane (of which 8,5000 were made) saw widespread use in training British Commonwealth aircrews in navigation, radio-operating, bombing and gunnery roles. Towards the end of the war, such was Shute’s celebrity that the Ministry of Information sent him to both the Normandy Landings and to Burma as a correspondent. For the development of a hydraulic retractable undercarriage for the Airspeed Courier and his work on R100 Shute was made a Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society.

After the war, in 1948 Shute flew to Australia in his Percival Proctor aircraft co-piloted by his friend the skier and author James Riddell, whose 1950 book Flight of Fancy is based on the experience. It was to mark a new era for Shute both man and writer, who ‘oppressed by British taxation’ would take the decision to permanently settle in Melbourne with his family, where he would initiate the third and most successful phase of his career as an author. Already well-known for his pre-WW2 flying adventures, followed by a series of popular war narratives, it would be his great Australian novels that cemented his reputation. Arguably the best of these is the apocalyptic post-nuclear On the Beach, which in 1959 graced the silver screen starring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Fred Astaire. Pessimistic and loss-making, as one critic puts it, On the Beach leaves the spectator with ‘the sick feeling that he’s had a preview of Armageddon, in which all contestants lost.’

Towards the end of his life Shute developed a passion for motor racing that found its way into On the Beach. As did many of his encounters with engineering. As Anderson’s lecture explains, Shute’s novels ‘are put together with precision and craftsmanship surely nurtured by his engineering background. In true engineering style nothing is wasted, everything works well and efficiently.’ Nevil Shute Norway died in Australia in 1960, aged 60.

Deep Heat: The new technologies taking geothermal energy to the next level

No. Not in the UK. The one location in the UK, with the prospect of delivering heat at around 150°C and a thermal-to-electrical efficiency of 10-12%,...