Stroll along Soho’s Frith Street and before long you’ll find a famous old café called Bar Italia. Look up and to the right of the first-floor window, and you’ll see a blue plaque put there by the London County Council on which are written the words: ‘In 1926 in this house John Logie Baird first demonstrated television’. London’s other blue plaque commemorating Baird – at his residence in Sydenham – simply states that the ‘television pioneer lived here’.

Put these two statements together and you get the nutshell summary of the invention and the innovator who presnted to the world a technology that in turn gave to its people (in the words of Apple’s Steve Jobs) ‘exactly what they want.’ By the year 2026 – a century after Baird demonstrated his fledgling ‘televisor’ to members of the Royal Institution and a reporter from The Times – according to Statista, there will be 1.8 billion ‘TV households’ worldwide each with, according to audience insight and data analyst Nielsen, 2.5 televisions per. Rarely has any technology had such influence over our everyday lives. As John Lennon said: ‘If everyone demanded peace instead of another television set, then there’d be peace.’

John Logie Baird – his birth certificate records his middle name as ‘Loggie’ – was born on 13 August 1888 in Helensburgh on the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. The fourth and youngest child of the Reverend John and Jesse Baird, by his early teens he had, as one biographer describes it, ‘developed a fascination with electronics and was already beginning to conduct experiments and build inventions.’ While reading electrical engineering at the Royal Technical College in Glasgow (now Strathclyde University) Baird’s studies were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, following which he volunteered for the British Army. Classified as unfit for active service he was employed in war work on munitions at the Clyde Valley Electrical Power Company. After the war, Baird embarked on the first of his idiosyncratic non-television-related entrepreneurial projects that would include the invention of the glass razor, his eponymous ‘thermal undersock’ and pneumatic shoes (later developed by the German Army doctor Klaus Märtens of Dr. Martens renown). But in 1919, Baird set sail to the Caribbean, where in Trinidad he established a jam factory, an enterprise thwarted – according to the Scottish Science Hall of Fame – by the island’s teeming insects that “either ran off with the sugar or landed in the hot vats of boiling preserve.”

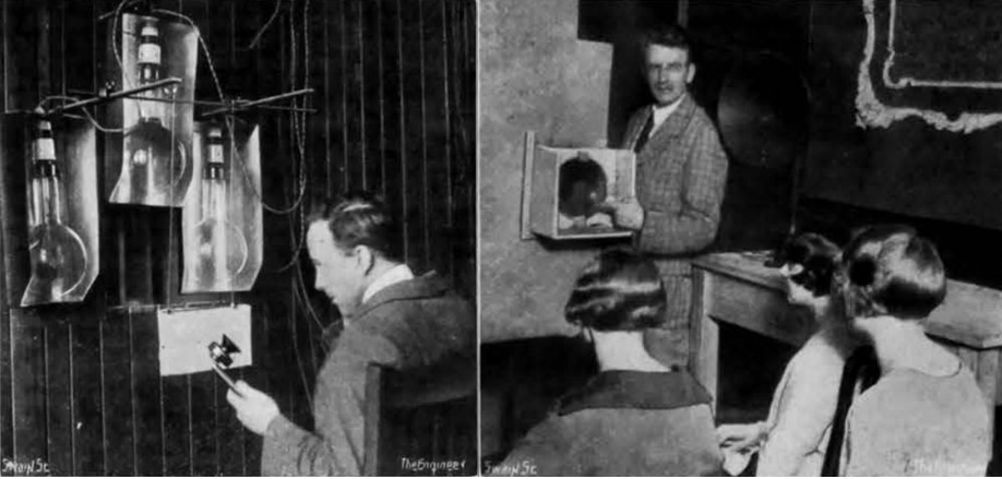

Back in the UK, in 1923 Baird rented a workshop in the Queen’s arcade in Hastings where he built – from components including an old hatbox, bicycle lamp lenses and sealing wax – the world’s first working television set. The following year, as Russell Burns explains in John Logie Baird: Television Pioneer, Baird demonstrated to The Radio Times that a semi-mechanical analogue television system could transmit moving silhouette images. But the system came with risks and, after being on the wrong end of a 1000-volt electric shock, Baird was evicted from his workshop, after which he relocated to London. Hoping to generate publicity for his invention, he visited The Daily Express where his reputation preceded him. One account of the meeting has a terrified newsman exclaiming: “For God’s sake, go down to reception and get rid of a lunatic who’s down there. He says he’s got a machine for seeing by wireless! Watch him—he may have a razor on him.”

Cathode-ray tubes are the most important items in a television receiver.

John Logie Baird (1888-1946)

Baird’s endeavours took a turn for the better over the following years. By adopting the thallium sulphide (Thalophide) cell that was making an impact in the development of ‘talking pictures’ in the US, Baird produced live, moving television images from reflected light. These images were first publicly demonstrated at Selfridges department store in early 1925. On 26 January 1926 Baird gave his historic first demonstration of true television images (i.e. live moving images with tonal graduation) at 22 Frith Street in London: the projection measured only 3.5 x 2 inches, with a scan rate of five pictures per second. On 28 January 1926 The Times reporter noted: “The image as transmitted was faint and often blurred, but substantiated a claim that through the ‘televisor,’ as Mr. Baird has named his apparatus, it is possible to transmit and reproduce instantly the details of movement, and such things as the play of expression on the face.” Further public demonstrations took the form of the world’s first colour transmission on 3 July 1928 when, using a system of scanning discs with three aperture spirals fitted with primary colour filters, Baird introduced the eight-year-old Noele Gordon (who went on to star in the television soap opera Crossroads) to the world. That same year Baird also demonstrated stereoscopic television.

Following his first long-distance transmission of a television signal between London and Glasgow, he set up the Baird Television Development Company that was responsible for the first transatlantic transmission from London to New York and the first British Broadcasting Corporation programmes. Other firsts followed thick and fast. In 1929, with Bernard Natan he founded France’s first television company, Télévision-Baird-Natan. In July 1930 the first piece of television drama ever to be produced in Britain – The Man With the Flower in His Mouth – was screened by the BBC as part of its 30-line experimental transmissions. Broadcast live from Baird company’s headquarters at Long Acre in London, the production was watched by the British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald who had one of the first of Baird’s ‘televisors’ installed at 10 Downing Street. In 1931 the BBC transmitted the Epsom Derby horse race – Baird’s first live outside broadcast.

Meanwhile, as the BBC’s website explains, “other inventors across the world had not been idle. Many scientists and engineers felt that mechanical television, as developed by Baird, using spinning discs, was not the answer”. They felt that the future lay in a form of electronic television being developed by Sir Isaac Shoenberg’s team at EMI in the UK. The BBC started to alternate between Baird’s (by now) 240-line transmissions and EMI’s electronic scanning system that had been improved to 405-lines following a merger with Marconi. Ultimately EMI-Marconi ousted Baird’s system, with Shoenberg spearheading the development of the Emitron camera tube to go with the hard-vacuum cathode-ray tube (CRT) that formed the basis of the television receiver. Baird responded by adopting technology developed by the American television pioneer Philo Farnsworth (notably the ‘Image Dissector’ camera), but was hampered by technical problems. When Baird’s Crystal Palace transmitter and studios were destroyed by fire in 1936, what the BBC describes as ‘the contest’ came to an end.

Baird continued in the field of electronic television, and in 1939 demonstrated a hybrid colour system using a CRT with colour filters mounted on a revolving disc – an innovation adopted by both CBS and RCA in the US. By 1940 he was working on the fully electronic Telechrome system that produced limited colour images and in late 1944 he gave the first demonstration of a practical fully electronic colour television display. His plans to make the proposed 1000-line Telechrome system – comparable with today’s HDTV – the post-war broadcast standard came to nothing when the overseeing Hankey Committee lost momentum, leaving the inferior 405-line standard to remain in place for decades until it was replaced by the 625-line system.

John Logie Baird died at home in Bexhill-on-Sea on 14 June 1946, and has received many posthumous accolades including that of being the only deceased subject of the television programme This Is Your Life. On 26 January 2016, to mark the 90th anniversary of the first public demonstration of live television, Google produced a ‘Doodle’ dedicated to ‘Mr. Baird, his strange machinery, and his lasting contributions to modern society. Without his genius, we would all have a lot more time on our hands.’ In 2021, the Royal Mint unveiled a John Logie Baird fifty pence coin commemorating the 75th anniversary of his death.

There have been many attempts to summarise Baird’s career and the ‘crystal bucket’ (a term coined by TV critic Clive James) that was to change the way we view the world. There aren’t many poems written about engineers and even fewer in Scots. And so it is left to the quill of poet Andrew Roxburgh McGhie (perhaps better known as Associate Director of the Laboratory for Research on the Structure of Matter at the University of Pennsylvania), who wrote: “There was an engineer sae bricht / Work’d ilka mornin’, noon and nicht / Until, at last, he got it richt / His lifelang mission / Aye, 'twas sic a bonnie sicht / Yon television”.

More from The Engineer

Emergency law passed to protect UK steelmaking

<b>(:-))</b> Gareth Stace as director general of trade body UK Steel, is obviously an expert on blast furnace technology & operation. Gareth...