‘Nobody can look at the Forth Bridge without being aware that it is great not only in size but in conception. It is a mighty work of engineering and it is also a work of art.’ So wrote Trystan Edwards of Sir John Fowler’s magnum opus in the Structural Engineer in 1925. But, warned the noted architect and town planner, in comparison with the Forth Bridge, ‘his other engineering achievements seem necessarily somewhat dwarfed.’ And yet these others were immense, including Fowler’s landmark work as chief engineer on the first underground railway – London’s Metropolitan Railway from Farringdon to Paddington – as well as much of what now makes up London Underground’s Circle Line.

Fowler also consulted on many other railways and bridges both in the UK and overseas, as well as proposing the ill-starred fireless locomotive, built by Robert Stephenson and Company. Such was his influence on the so-called age of ‘railway mania’– the second half of the nineteenth century during which £3bn was invested in railway building – that on his death in the twilight of the century, the Institution of Civil Engineers proclaimed in its 1899 obituary that Fowler had been ‘one of the most eminent of engineers whose names are associated with the great material progress effected during the Victorian era’. In response to Fowler amassing a colossal personal wealth from his endeavours – for his work on the Metropolitan Railway alone he was paid £152,000 (£17.1 million today) – the industrialist Sir Edward Watkin commented acidly that ‘no engineer in the world was so highly paid’.

Engineers… should not lend their name to any project that does not promise to be beneficent to man

Sir John Fowler, 1st Baronet (1817-1898)

John Fowler was born in 1817 at Wadsley Hall, Yorkshire, described in The Life of Sir John Fowler, Engineer (1900) by Thomas MacKay as ‘the birthplace of one who played an important part in the economic revolution which was then pending’. It was the age of steam power and spinning machines – a mere decade since the appearance of the first public passenger railway – and one that would be dominated by Brunel and Bazalgette, with Fowler’s name ranking alongside. MacKay notes that while Fowler’s family was connected to the ‘vanishing order of things’, and while his land-surveying father could resist ‘the unsolved problems of the industrial system’, his son ‘threw himself into the stream of new industry’. Sent to be privately educated at Whitley Hall, by his own admission he was an outstanding pupil: ‘I was fairly quick in elementary scholarship, and in mental arithmetic was decidedly beyond the average of boys and men; a gift which was of great convenience and value in after life.’

On finishing school Fowler trained as an engineer under the Sheffield contractor John Towlerton Leather, assisting with the construction of the Redmires and Crooke’s Moore reservoirs. He also worked with Leather’s uncle on the Aire and Calder Navigation canalisation project, as well as with early steam locomotive builder John Urpeth Rastrick. Following a period of consulting in the Yorkshire area he relocated to London in 1884, joined the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and in 1849 became one of the first members of the Institution of Civil Engineers. In the 1860s he would become the latter’s youngest president.

The first of Fowler’s great projects originated in 1853 when he was appointed chief engineer of the capital’s Metropolitan Railway. It was to present a challenge that drew heavily on Fowler’s self-reliance. While supporters of the scheme saw the opportunity to make history with an underground railway, there was public doubt over the feasibility of the project. The directors were constantly being told, writes Fowler’s obituarist, that ‘they had embarked their money and that of the shareholders in an impossible enterprise’. In a cascading set of objections, ‘engineers of eminence assured them they could never make the railway’, or if they did ‘it wouldn’t work’, and if it worked ‘nobody would travel by it’.

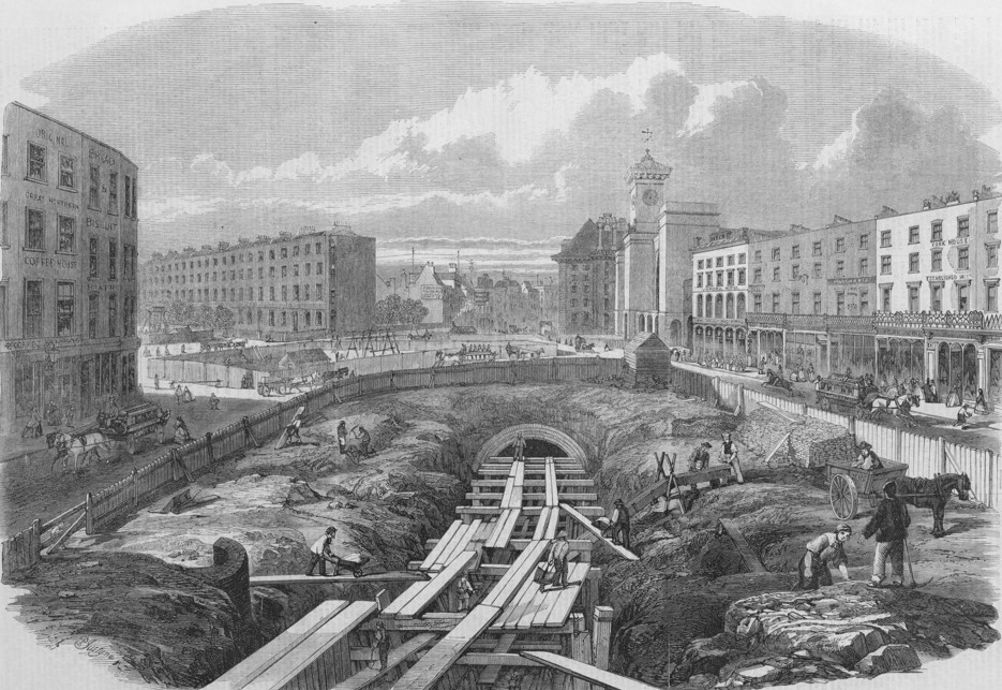

All of which apparently meant little to Fowler: ‘At such times the directors would say to Mr. Fowler, “We depend on you, and as long as you tell us you have confidence we shall go on.” It was a heavy load to put on the shoulders of a man who had already sufficient to attend to in combating the physical difficulties of the affair. Yet Mr. Fowler never flinched. He had made up his mind that the railway could be constructed and that it would answer its purpose.’ And so the shallow cut-and-cover trenches were created beneath New Road, with tunnels and cuttings beside Farringdon Road. It took a decade to complete, but on 10 January 1863 the line opened with gas-lit wooden carriages pulled by steam locomotives. As John R Day and John Reed’s The Story of London’s Underground confirms, the world’s first passenger-carrying designated underground railway was now functioning, and would continue to serve, after many extensions and upgrades, for seven decades until 1933.

Realising the quantities of smoke and steam emitted by conventional locomotives would cause environmental problems in underground railway scenarios, Fowler set about designing a fireless steam locomotive. The idea was to use exhaust condensing techniques in combination with large quantities of fire bricks that would retain sufficient heat to generate steam when the train was in covered sections. Trials were held on the Great Western Railway in 1861 and in London the following year, during which pressure problems were identified – the first trial almost resulted in the prototype exploding – and the scheme was abandoned. The locomotive was sold, and the whole episode – which was an acute embarrassment to Fowler – was quietly forgotten. By the end of the century ‘Fowler’s Ghost’, as it had been dubbed by The Railway Magazine, had been scrapped.

Fowler was undeniably better at building bridges than he was steam engines, and during his career he designed several. His first railway bridge (also the first of its kind to cross the River Thames) was the Victoria Railway Bridge (now called Grosvenor Bridge), connecting Battersea to Pimlico and built between 1859 and 1860 to carry two tracks into Victoria Station. This was followed by the 13-arch Dollis Brook Viaduct – the highest point on the London Underground above ground level – for the Edgeware, Highgate and London Railway. There were also two Severn railway cast iron arch crossings – the Victoria and Albert Edward bridges – which are both in use today.

During this period of domestic bridge building he also consulted overseas on engineering projects in North America, Europe, Australia and North Africa. In the late 1860s he travelled to Egypt where he worked on a number of projects for the Khedive, including a railway to Khartoum in Sudan that was not completed until after Fowler’s death. While working in the region, Fowler undertook a survey of Upper Nile Valley resulting in accurate maps that were to prove invaluable in the 1884-85 Nile Expedition to relieve Major-General Gordon at the Siege of Khartoum. In recognition of his cartographical efforts, in 1885 Fowler was made Commander of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George.

Arguably the jewel in Fowler’s engineering crown was the Forth Bridge, now one of Scotland’s most recognisable landmarks. A steel cantilever construction designed by Fowler and Benjamin Baker, construction started in 1882, and it was opened on 4 March 1890 by the future Edward VII. At the time it had the longest single cantilever span (521m x 2) of any bridge in existence, and has since only been eclipsed by the Pont de Québec (549m) completed in 1917. As Fowler’s ICE obituary states: ‘It was not only far larger than any railway bridge previously built, but it was of a very novel design. It was commenced with the full consciousness that its execution bristled with unknown difficulties, which would have to be met and conquered as they made themselves evident. Yet Sir John Fowler was satisfied that the project was feasible, and he did not doubt that he and his colleagues would be quite able to accomplish it. In this instance he was fortunate to have clients who had a perfect belief in his powers, and who could command the required capital.’

Accolades followed. Fowler was created Baronet Fowler of Braemor, and along with Baker received an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh in recognition of his engineering contribution to the Forth Bridge. In 1892, the French Academy of Sciences doubled the purse for their Poncelet Prize before jointly awarding it to Fowler and Baker. And although he continued to consult, the bridge was to be his swansong, after which he spent much of his time deerstalking on his vast Scottish estate.

More from The Engineer

Klein Vision unveils AirCar production prototype

According to the Klein Vision website, they claim the market for flying cars will be $1.5 trillion by 2040, so at the top end $1 million per unit that...