Despite being one of the most important engineers and aerodynamicists of his age, Gustave Eiffel’s reputation ultimately rests on two instantly recognisable landmarks: the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty. His monumental career spanned seven decades, from his early civil projects such as the Bordeaux bridge to his later scientific research into air resistance. Living well into his nineties, Eiffel is remembered the greatest engineer France has ever produced.

Alexandre Gustave Bonickhausen dit Eiffel was born in Burgundy in 1832 at a time when France, under the rule of Louis Philippe I, was in a period of rapid industrial, economic and colonial expansion. His mother had a successful charcoal business and his uncle distilled vinegar: the former providing the undistinguished school student with a stable financial background, while the latter supplied an improvised education, teaching the young Gustave the rudiments of an eclectic set of disciplines that included chemistry, mining, theology and philosophy. This unorthodox background bore fruit to a degree when he was accepted by the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris, where we know he specialised in chemistry and we think developed his passion for engineering. His enthusiasm for technology was nurtured by the fact that in 1855 Paris played host to the second World’s Fair, for which his mother supplied him with a season ticket. A quarter of a century later his famous tower would be the centrepiece of another technology showcase, the 1889 Exposition Universelle.

“Can one think that because we are engineers, beauty does not preoccupy us, or that we do not try to build beautiful, as well as solid and long-lasting structures?”

Eiffel’s career got off to an uncertain start, with family disputes and employer bankruptcies obstructing his path. But eventually he fell into the orbit of railway engineer Charles Nepveu, managing director of two factories in Paris owned by the Compagnie Belge de Matériels de Chemin de Fer, and an influence on Eiffel’s initial success. His first significant project under Nepveu was assisting on a 500m iron girder railway bridge over the river Garonne at Bordeaux. Following his boss’s resignation, Eiffel was promoted to manage the entire project, subsequently rising to become principal engineer of the Compagnie Belge. By 1865 dwindling market conditions meant that Eiffel had little choice but to go it alone as an independent engineering consultant. It was a move that would see him building locomotives for the Egyptian government and assisting with the design of the exhibition hall of the 1867 Exposition Universelle, which would lead him into researching the structural properties of cast iron. By 1868 he was sufficiently established to form ‘Eiffel et Cie’ (Eiffel & Co) in partnership with his fellow École Centrale graduate and bridge builder Théophile Seyrig.

Their first projects were a railway terminus for the line from Vienna to Budapest, and a bridge over the river Douro in Portugal. At the time, this bridge represented the longest arch span (160m) ever built, and was finished in less than two years for just under a million French francs. Within a decade, Eiffel was France’s most famous engineer, and by 1879 he had parted company with Seyrig, and was trading under the name Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel. Such was his reputation that he was routinely commissioned for major works without having to go through the process of competitive tendering. Eiffel also started to introduce his concept of exporting prefabricated bridges as far afield as China that could be assembled by bolting them together rather than riveting. At the same time Eiffel took on key technical personnel –including Franco-Swiss structural engineer Maurice Koechlin and French civil engineer Émile Nouguier – who were to play vital roles in the design of the Eiffel Tower.

In 1881 Eiffel became involved in a project to build a neo-classical monument that was to be a gift from France to America to commemorate the centenary of American Independence. The Statue of Liberty (more correctly ‘Liberty Enlightening the World’) in New York Harbor was the brainchild of French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi who had conceived of the Roman goddess Libertas bearing a torch in her right hand, while in her left, a tablet inscribed with “JULY IV MDCCLXXVI” (July 4, 1776). Bartholdi required an engineer to help him bring his design to fruition and Eiffel, duly enlisted because of his vast knowledge of wind stresses acquired during a career designing bridges, created the four-legged pylon that supports Liberty’s copper sheet exterior. Eiffel built the statue at his works in Paris before shipping it in boxes to America for reassembly on Bedoe’s Island, where it was dedicated by President Grover Cleveland on 26 October 1886, a decade after the actual centenary.

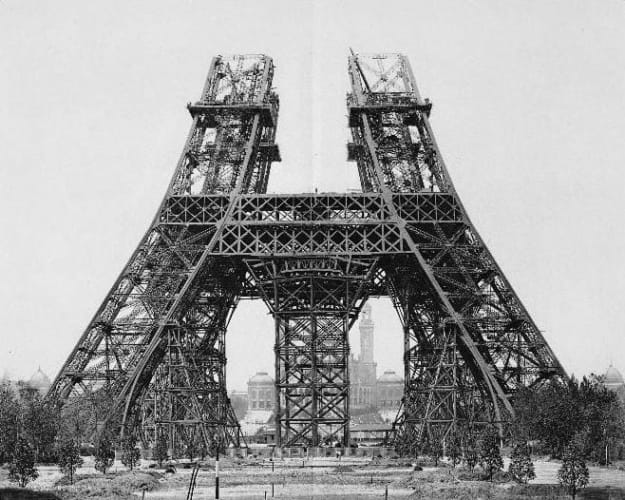

When the idea for erecting a tower in central Paris that would be a focus for the 1889 Exposition Universelle was first floated, Eiffel showed no interest other than to tolerate Koechlin and Nouguier working on plans for ‘a great pylon’ in their own time. But, as the concept gathered momentum – structural flourishes were added by architect Stephen Sauvestre in the form of decorative arches at ground level, a glass pavilion on the first level and a cupola at its summit – Eiffel displayed more enthusiasm, delivering a paper on the project’s technical challenges to the Société des Ingénieurs Civils. Political inertia at government level put the idea on hold until a budget for the exposition was eventually passed by Minister for Trade, Edouard Lockroy, who then released a schedule of regulations for what was officially an ‘open’ competition but was transparently biased in favour of Eiffel’s pre-existing design.

At this point Eiffel pricked up his ears and started to enter into contracts for the proposed 6.5 million-franc tower as a private individual, rather than as a representative of his own company. As construction got underway on the Champ de Mars, the artistic community mobilised a protest against this “ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic smokestack” by way of a petition from the Committee of Three Hundred, sent to the Minister of Works and published in Le Temps newspaper. Eiffel retaliated by comparing his oeuvre to the Pyramids: “Why should that which is admirable in Egypt become hideous in Paris?” He also declared his tower would be the highest structure ever built, which remained true from its inauguration in 1889 until 1929, when it was overtaken by New York’s Chrysler Building.

Reaction to the tower was mixed. While Thomas Edison gushed over “Monsieur Eiffel the Engineer, who has the greatest respect and admiration for all Engineers including the Great Engineer the Bon Dieu,” man of letters Guy de Maupassant showed his displeasure at a vulgar edifice he regarded as his ‘arch nemesis’ by dining at the restaurant on the deuxième étage every day, famously claiming: “inside the restaurant was one of the few places where I could sit and not actually see the Tower.”

If the tower had been a cause célèbre, what followed was nothing less than an outright public scandal. Eiffel became embroiled in the French attempt to build a canal crossing across the Panama isthmus in Central America. His involvement was as a sub-contractor in charge of designing and manufacturing the canal locks. But when the French Panama Canal Company went into liquidation, he was caught up in a political and financial melee, with the result that in 1893 he was charged along with the directors of the company with misuse of funds. Eiffel was found guilty, fined 20,000 francs and sentenced to two years imprisonment. Although acquitted on appeal, his reputation was in tatters, leading to his resignation from the Board of Directors of Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel. At his own insistence his name was expunged from the organisation (only to be reinstated in 1937, 14 years after his death).

"Paris must groan beneath the shadow of the iron version of the Tower of Babel" - read The Engineer's contemporaneous take on Eiffel's most famous structure

The remainder of Eiffel’s career was spent in the relative obscurity of scientific research in the field of aerodynamics. He had a laboratory at the foot of the tower that bore his name and, by experimenting with dropping objects from his tower, proved that the air resistance of a body is related to the square of the airspeed. In 1909, he built a wind tunnel to investigate the characteristics of aerofoils that were finding their way into technology under development by aviation engineers such as Louis Blériot. In 1913 he was presented with a medal by the Smithsonian Institution for his work in aerodynamics, with Alexander Graham Bell stating that Eiffel’s writings on the subject were ‘classical’ and had “given engineers the data for designing and constructing flying machines upon sound, scientific principles.”

Gustave Eiffel died in 1923 while listening to Beethoven’s 5th symphony.

Guest blog: exploring opportunities for hydrogen combustion engines

"We wouldn't need to pillage the environment for the rare metals for batteries, magnets, or catalisers". Batteries don't use rare...