Whilst much has been made of UK engineering’s response to the Covid-19 crisis, there’s a growing sense that this impressive mobilisation of the manufacturing base is merely a dress-rehearsal for an even more daunting challenge: reducing the UK’s carbon emissions to nothing by 2050.

Because whilst politicians and businesses across the economy will all have a role to play, the quest to meet the net zero emissions targets that are enshrined in British law is first and foremost an engineering challenge that will require unprecedented levels of innovation in almost every area of energy technology: from carbon capture and storage, to modular nuclear reactors, battery technology, offshore wind, solar and more.

There is, quite clearly, no silver bullet. But one energy source that’s considered an increasingly vital component of this low carbon future, and in which the UK is very well-placed to develop a competitive edge, is hydrogen.

Abundant, versatile, energy dense and clean at point of use, hydrogen has long attracted a vocal band of evangelists, who have trumpeted the gas’ potential for heating our homes, fuelling our transport and generally reshaping our energy economy.

The problem is that the bulk of the hydrogen currently used is so-called “brown hydrogen” derived from fossil fuels using processes that the International Energy Authority (IEA) says is responsible for around 830 million tonnes of CO2 emissions per year.

Clearly, if it’s to truly deliver on its undoubted potential, cleaner methods of production are essential, and the quest to develop this missing part of the jigsaw is a major driver of innovation.

Initially, this is likely to fuel greater investment in blue hydrogen production, where carbon capture and storage (CCS) is used to capture the CO2 produced by existing processes.

But it’s the developments in green hydrogen production - using giant renewably powered electrolysers to extract hydrogen from water - that are perhaps most exciting of all.

Hydrogen produced in this way could – it’s claimed - play a key role in decarbonising industrial processes, domestic heating and transport, whilst offering an elegant method of storing excess renewable energy.

One of the UK’s pioneers of green hydrogen production is Sheffield based electrolyser manufacturer ITM power, which produces scaleable modular PEM (polymer electrolyte membrane) electrolyser systems for a range of applications.

The company - which is in the process of moving into a new 1GW per annum facility claimed to be the largest of its kind in the world - is perhaps best known for its network of renewably powered hydrogen filling stations which can be found on Shell forecourts around the UK. But it’s now also involved in a number of major projects exploring the feasibility of green hydrogen production for industrial applications.

One of the key initiatives here is Gigastack, an ITM led project, that has received £7.5m funding through the UK government’s hydrogen supply competition to explore how the costs of electrolytic hydrogen for industrial use could be reduced.

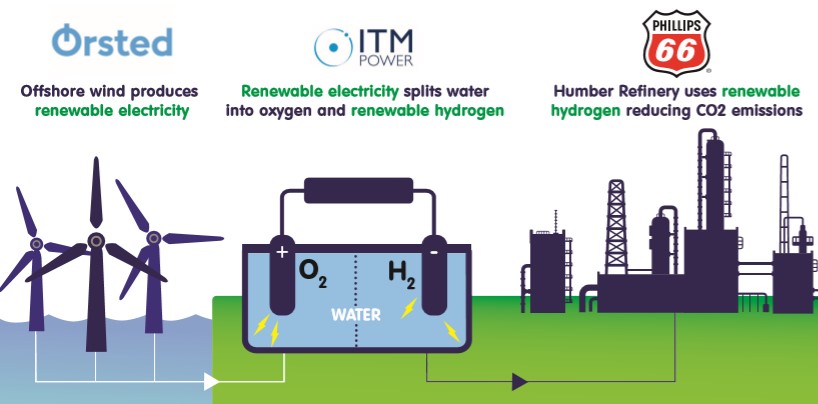

The project is exploring the development of a system that will use electricity from Orsted’s Hornsea Two 1.4 GW offshore wind farm to power giant electrolysers at a substation in Humberside that will in turn generate renewable hydrogen for the Phillips 66 refinery.

ITM has already developed designs for a modular 5MW electrolyser stack as part of initial feasibility study and as part of the second phase will conduct a front end engineering study on the development and integration of a 100MW electrolyser made of up 20MW modules.

The company is also involved in an effort to build what will be the world’s largest PEM electrolyser at Shell’s Rhinleand Refinery in Wesseling, Germany.

The five year REFHYNE project which kicked off in 2018, will see a 10MW electrolyser, consisting of two 5MW modules, integrated into refinery processes such as desulphurisation and hydrocracking. The system is expected to supply around 1300 tonnes of hydrogen per year, which is around one per cent of the plant’s annual hydrogen needs.

Once up and running, the facility will become the largest green hydrogen production facility in the world, overtaking the 6MW H2Future plant at steelmaker Voestalpine’s site in Linz, Austria.

For ITM CEO Graham Cooley the opportunities presented by this market alone are huge: “The biggest initial opportunity is decarbonising the existing market for hydrogen,” he told The Engineer. “If you just decarbonise 10 per cent of the hydrogen used in refineries that is a market size of 90 billion Euros.”

But whilst ITM Power is primarily focused on driving the market through industrial applications, others – such as JCB heir Jo Bamford – are concentrating on different markets.

Owner of green hydrogen production company Ryse and UK bus manufacturer Wrightbus, Bamford recently outlined an ambitious plan to use buses to catalsye the UK’s hydrogen economy.

Wrightbus has already supplied a number of hydrogen fuel cell powered buses around the UK and is poised to deliver a fleet of 20 vehicles to Transport for London. But Bamford has ambitions to scale this up rapidly, and earlier this summer unveiled a “fully-costed” vision on how the private sector and government can work together to to bring 3,000 hydrogen buses to the streets of the UK by 2024.

There are so many different variables around getting hydrogen going, but in essence you need volume and a captive customer

Jo Bamford - Ryse / Wrightbus

Under his plans, these new buses along with five new zero-emission hydrogen production plants dotted around the UK coast will be used to kick start the UK’s hydrogen economy and create thousands of new jobs. Ryse has already applied for planning permission to build the first of these at a site near Herne Bay in Kent, where it will be powered by electricity from Vattenfall’s Kentish flats offshore wind farm and use electrolysis technology supplied by Norwegian firm Nel Hydrogen.

Calling on the government to set aside 10 per cent of its National Bus Strategy fund for hydrogen Bamford said: “You have to start somewhere, there are so many different variables around getting hydrogen going, but in essence you need volume and a captive customer – and if you’ve got 200 buses coming back to a bus depot every night to be filled up you can get it going.”

Whilst Bamford plans to usher in the hydrogen economy via heavy transport, other projects currently in the pipeline are focused on producing green hydrogen for the gas grid.

One such initiative is the recently launched NortH2 project, a project involving Shell, Groningen Seaports and Dutch gas network operator Gasunie that will see a new “mega offshore wind farm” in the North sea feed a giant hydrogen production facility in the Netherlands seaport of Eemshaven. Green hydrogen produced at the site will be transported along existing gas infrastructure to customers throughout Northwest Europe.

The project’s ambition is to generate around 3 to 4GW of offshore wind energy by 2030, and as much as 10GW by 2040. Depending on the outcome of an ongoing feasibility study, the consortium hopes to produce first hydrogen by 2027.

Whilst NortH2 will be carrying electrolysis on shore, other efforts are taking a slightly different approach by exploring how existing offshore infrastructure could be adapted and used to carry out production.

Led by Dutch exploration and production company Neptune Energy the PosHYydon project plans to demonstrate how hydrogen could be produced on existing oil and gas platforms using electricity generated by offshore wind.

The project will see the installation of a green hydrogen production facility on Neptune Energy’s Q13a platform, an electrified oil and gas platform in the North Sea just off the coast of Scheveningen in the Netherlands.

Seawater will be pumped into containerised units on the platform, where it will be desalinated and then fed into an electrolyser.

The facility will receive green electricity by cable from the shore but will simulate generation from the nearby Luchterduinen offshore windfarm. It’s expected to produce approximately 3000 – 4000 Nm3 / day of H2 for the Gasunie grid.

Neptune Energy’s Patrice Hijsterborg told The Engineer that the aim of the two year project is to demonstrate how hydrogen production could represent a sustainable future for oil and gas platforms that are nearing the end of their lives. “Neptune wants to demonstrate that H2 can be handled and treated on a live, producing oil & gas platform,” he said. “The long term view is that Neptune gas infrastructure can be utilised for offshore renewable energy, and therefore share cost with producing our relatively low carbon North Sea gas.”

Meanwhile, the UK led ERM Dolphyn project is going one step further, and looking at producing green hydrogen from electrolyser units directly coupled to floating wind turbines situated far out at sea.

Led by environmental consultant ERM, the project has received £3.12m from the government’s hydrogen Supply programme and, following the completion of an initial proof of concept, is now entering its next phase.

Project director, ERM partner Kevin Kinsella explained that the team is currently focused on getting an initial 2MW unit up and running in a consented area around 20km off the coast of Aberdeen, followed by a 10MW unit pre commercial unit at the same location. The ultimate aim is deploy a 4GW array of floating wind turbines in the North Sea by the early 2030s.

Whilst hydrogen generated by the initial units will be exported to the shore via a three-inch diameter flexible pipe, Kinsella said that the larger commercial scale field will most likely connect into an existing repurposed offshore pipeline.

There’s no reason at all why, by the end of the century, the whole of UK heat couldn’t be provided by green hydrogen from offshore North Sea wind

Kevin Kinsella - ERM Dolphyn project director

Explaining the decision to directly couple the electrolysis to the turbine, Kinsella said that the team initially explored a number of options, such as bringing power back to a centralised platform with electrolysers before piping hydrogen back to shore, or performing electrolysis onshore, but went for direct coupling as it avoids the need for expensive cables, switchgear, and grid connections. “It’s a much cheaper way of doing it over long distances and you don’t get the energy losses that you do with bringing it back electrically,” he said.

Freeing the system from the constraints of grid connectivity also makes it easier to build further out to sea where the wind resource is more plentiful, and it’s possible to build large scale installations without impacting shipping routes or raising environmental concerns.

Kinsella said that a 4GW Dolphyn array could produce enough hydrogen to heat 1.5 million homes, and could ultimately transform the UK’s energy landscape. “There’s no reason at all why, by the end of the century, the whole of UK heat couldn’t be provided by green hydrogen from offshore North Sea wind”, he said.

It’s a tantalising vision, and one which is well within the UK’s grasp, not least thanks to the wealth of expertise and infrastructure that can be found in its offshore oil and gas industry.

President of the Energy Institute and former UK National Grid boss Steve Holliday told The Engineer that the sector’s buy-in will be crucial. “The only way we’re going to ensure the world has energy supplies, and at the same time making sure we’re cleaning our energy up…. is with the huge engineering, scientific and financial strength of the oil and gas industry,” he said. “They have a huge part to play. And this particular topic is just another example of where they can bring all of those skills and experiences to bear.”

Oil and Gas UK policy manager Will Webster, agreed that the sector has an important role to play and that green hydrogen could represent a major opportunity as we-transition to a zero carbon economy. “Many energy transition technologies are an opportunity for existing oil and gas businesses,” he said. “Offshore wind (fixed and floating), carbon capture and hydrogen are all areas which have transferable skills and expertise from the offshore oil and gas sector including project management, safety disciplines, operations, subsurface data analysis and logistics”

In Holliday’s view, what’s required now is some serious government intervention aimed at ensuring the sector has the best possible chance of delivering on its promise. “It feels to me a little like the world we were in a decade ago with zero carbon solar and wind,” he said. “We needed to kickstart those industries in the UK with incentives and those incentives worked. Offshore wind’s a perfect example. You were looking 3 /4 years ago at £140 /MW of offshore wind and now they’re coming in at the high £30s. We’re going to need to incentivise some scaling up of green hydrogen in order to bring the costs of that technology down to a level that means it’s going to be economic and logical to tie it in with the wind and the solar.”

This is an opportunity not just on our own journey to net zero in the UK but to actually create some industry that is very competitive and can be exported around the worldSteve Holliday - President, Energy Institute

Echoing the call for incentivisation, Jo Bamford called on the government to prioritise hydrogen over other more crowded fields of energy technology, such as batteries. “Every country in the world is going to come out of the crisis with plans to revitalise their own economy and every single one of those plans is going to be around how to do we make it green. And if every single one of them is going to chase batteries, it looks like a crowded field to me. As a businessman you go somewhere where you can compete and come out on top. There are far less people chasing hydrogen.”

There’s certainly a strong sense that the technology plays to many of the UK’s existing strengths: “We’ve got a massive renewable resource on our doorstep which is great advantage for us,” said Steve Holliday “This is an opportunity not just on our own journey to net zero in the UK but to actually create some industry that is very competitive and can be exported around the world.”

Indeed, in the form of ITM Power, the UK is already home to one of the world’s biggest electrolyser manufacturers, something which ITM’s Graham Cooley believes deserves a little more recognition. “We don’t have the world’s largest battery factory, we don’t have the world’s largest heat pump factory , we don’t have the largest solar cell producer and we don’t have the world’s largest wind turbine blade manufacturer – what we do have is the world’s largest electrolyser factory in Sheffield. And we ought to be singing from the rooftops about that!”

ERM’s Kevin Kinsella agreed with the positive outlook. “We’re in the best position in Europe, having the best wind resources by far. We have a leading offshore oil and gas industry and offshore wind industry, supported by the best supply chain in Europe, and all of the technical resources and knowhow to deliver it. With Net Zero by 2050 written into UK law, this is a fantastic opportunity for the oil and gas industry to transition smoothly from fossil fuels to green energy, using the same skills and resources, and at the same time become a net exporter of green energy to Europe.”

Comment: New oil is a lose-lose for the offshore economy

The spill map from the <u>every day</u> link in the report looks to be roughly 400km × 400km @ say 100m average depth = 16,000 cubic <b>kilometres...