In February last year (2022) Europe was on the brink of war. Two months prior, as Russian forces gathered along Ukraine’s eastern border, the price of gas in the UK had reached record highs, passing 450p per therm for the first time ever. On March 7th 2022, around two weeks after Putin’s ‘special operation’ got underway, the price spiked to nearly 540p, and the UK was facing a major energy crisis.

While Ukraine continues to endure incredible suffering, the whole of Europe has been impacted by the war, with the UK particularly exposed to Russia’s weaponisation of gas supplies. Gas accounts for around 40 per cent of electricity generation and 85 per cent of domestic heating, a recipe for energy prices in the UK to skyrocket in line with a volatile wholesale market. For some consumers, bills have risen by 300 per cent over the course of 12 months – even with a price cap in place - and many businesses are simply being squeezed out of existence.

Most initiatives have been half-baked ideas without proper financial support. Furthermore, there has been a lack of focus or support in developing the skillsets among the sector which has also undermined efforts

Dr Salvador Acha - Imperial College London

Much of this is beyond our control, geopolitical events and cold market economics combining to immiserate the masses. However, the UK’s near total reliance on gas for domestic heating is further compounded by the state of the country’s building stock, large swathes of which is poorly insulated and energy intensive to warm. As gas prices have soared, the UK’s draughty homes have been plunged into energy poverty. We may well lay blame with Putin, but the current situation is also a failure of policy.

“The Conservative Party has failed to properly support through policies and funding the decarbonisation of buildings in the UK,” Dr Salvador Acha, from the Department of Chemical Engineering at Imperial College London, told The Engineer.

“Most initiatives have been half-baked ideas without proper financial support. Furthermore, there has been a lack of focus or support in developing the skillsets among the sector which has also undermined efforts.”

Dr Acha is the lead author of a new report that highlights the UK’s shortcomings as well as some of the successful policies that have been implemented by its continental neighbours. Decarbonising Buildings: Insights From Across Europe, focuses on four key challenges the UK is facing - 1) improving efficiency standards, 2) decarbonising heat, 3) energy renovations, and 4) fostering skills and training. According to Dr Acha, hitting net zero targets will require all four pieces of the jigsaw to fall into place, and lessons for each area can be taken from different countries across Europe.

“The KfW Efficiency House standard from Germany has been operating for more than 15 years, informing how gradual improvements of the building stock is progressing, and this helps to identify properties that fall behind and which need upgrades,” he said. “We think such a standard could be applied with success in the UK.”

Derived by German development bank KfW, the Efficiency House classification rates dwellings against the German Building Standard for new homes. A KfW 100 level corresponds to a building that uses 100 per cent of the energy of a standard new build, while a KfW 55 building uses just 55 per cent.

The programme also includes grants and loans to enable owners to improve their efficiency rating, supporting the gradual decarbonisation of Germany’s housing stock. In the first 10 years of its operation, it’s estimated the KfW standard resulted in an annual reduction of 8.3 million tonnes of CO2 emissions. By comparison, the UK is a long way off the pace.

“Studies show the UK’s 28.6 million homes are among the least energy efficient in Europe and lose heat up to three times faster than on the continent, making people poorer and colder,” said Dr Acha.

“Energy efficient housing and properties has not been a priority in the construction sector for many generations. The argument has been that improving the quality of the building would increase costs substantially. And for a market where housing is already very expensive, this would risk leaving many people behind.”

Short-term thinking and policy failure has meant that not only is the UK’s ageing housing stock lagging behind for energy efficiency, new builds are often not even meeting net zero criteria. According to the UK government’s Environmental Audit Committee, the existing Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) scheme currently used to assess buildings is not fit for purpose, largely due to the failings in the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) that determines ratings. Incorporating a more holistic, KfW-style standard for energy efficiency should be a cornerstone of any serious decarbonisation programme.

“I would suggest for the government to liaise with organisations such as CIBSE (Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers) and academia to maximise the use of digital technologies to monitor and benchmark a significant proportion of the UK housing stock,” said Acha.

“This would allow us to keep track of progress for a wide range of property types and devise EPC standards that adapt to each property type giving greater insights into how each building could gradually improve. This effort would allow us to develop bespoke EPC standards and performance indicators for a wide range of properties.”

The EPC criteria almost certainly needs a rethink, but it is just one factor holding back the UK’s domestic decarbonisation efforts. Over the last 10 years, for example, housing retrofit has actually slowed down due to government incentives being scrapped, according to Acha.

At a time when building retrofit has never been more important, the UK has been abandoning policy that encourages homeowners and landlords to invest in the necessary work. As with standards and measurements, the Imperial report can point to exemplars from abroad. One of the most successful retrofit policies highlighted in the paper is Italy’s Superbonus scheme. Introduced in July 2020 to head off the economic headwinds of Covid, it offers homeowners a tax credit of up to 110 per cent on the cost of eligible energy renovations. By March 2022, the scheme had approved over 122,000 applications, provided approximately €21 billion worth of support, and created 150,000 new jobs across the construction sector.

“The Superbonus scheme in Italy…has been very successful,” said Acha. “In the UK we think such a policy would help families improve the quality of life and the value of its property, while also fostering job growth in a period when a recession is looming. Also, the Rénov public renovation service programme in France is worth highlighting as it is a free independent public service providing support to homeowners who wish to renovate their properties.”

In November 2022, as a winter of potential blackouts closed in, the UK government finally announced new action on retrofit. The £1billion ECO+ scheme, due to run from spring 2023-2026, will target homes with EPC ratings D or lower. Households that successfully apply can expect a grant of around £1,500, perhaps enough to cover loft or room-in-roof insulation, generally the lowest hanging fruit in inefficient homes. Although Acha and his Imperial colleagues welcomed the announcement, he believes it barely makes a dent in what’s needed.

“To get the industry moving in the right direction I would suggest allocating £50 billion to kick-start a nationwide building retrofit effort,” he said. “This would help strengthen the workforce and supply chain, giving business confidence that we are in this for the long haul.”

Given that initial estimates for the UK’s two-year energy price freeze announced in October 2022 were between £70bn and £140bn, £50bn for a comprehensive national retrofit scheme starts to look less outrageous. Not only would the spending stimulate huge growth across the construction sector, but renovations would also add value to people’s homes and cut bills, rather than supporting the bottom line of energy companies.

The result would be reduced energy demand and emissions through winter, with insulation also protecting against the extreme summer temperatures of heatwaves. In this respect, insulation should be the top policy priority when it comes to retrofit, the horse before the cart, so to speak. Decarbonising heat is equally important, but for many UK homes this will only be possible once structural renovations have taken place.

“Improving the building quality reduces demand significantly and hence reduces energy costs and enhances the energy security of the country,” said Acha. “Whereas installing heat pumps mostly impacts carbon reduction efforts but if the quality of the building is poor, energy use and costs do not come down significantly.”

In reality, renovations and heat decarbonisation must be rolled out concurrently where possible. Domestic heat pumps are already playing a role, albeit on a relatively small scale and with a large upfront cost beyond the means of most, even considering the £5,000 grant available in the UK. For densely populated areas, heat networks – or district heating – can deliver low carbon heat on a mass scale, rapidly weaning entire neighbourhoods off fossil fuels.

Set up around four years ago, Vattenfall Heat UK is a subsidiary of Sweden’s Vattenfall, the state-owned power company with assets across much of northern Europe. Vattenfall’s own decarbonisation efforts have seen an expansion into wind and other renewables, alongside its existing nuclear and fossil-fuel generation. The parent company is also the biggest retailer of heat in Europe, with Berlin, Amsterdam and Uppsala already home to its district heating networks. It now has its sights set on the UK market.

“We’ve got around two million customers on heat networks there at the moment across Germany, Netherlands and Sweden,” said Stuart Allison, interim managing director at Vattenfall Heat UK. “We believe there’s a market there, that the UK is now taking the decarbonisation of heat seriously.”

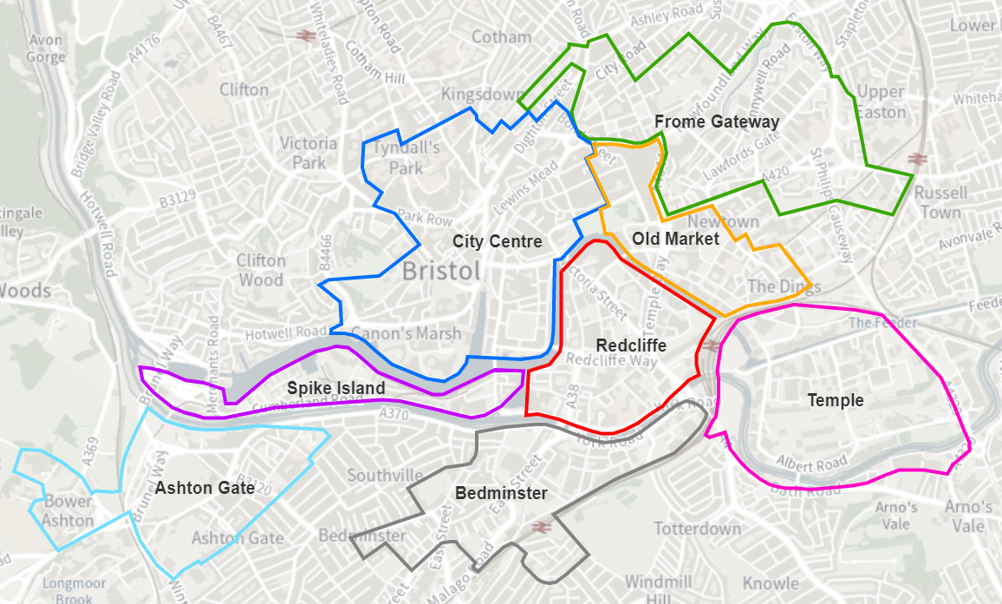

At the time of writing, Allison had just taken part in a signing ceremony for Bristol City Leap, a long-awaited partnership programme led by Bristol City Council and US energy services firm Ameresco, with Vattenfall Heat UK a key subcontractor. Aiming to decarbonise the city as soon as 2030, the first phase of the 20-year project will see an expansion of Bristol’s heat networks and the installation of hundreds of megawatts of new low carbon generation, alongside a widespread programme of building renovations to boost energy efficiency.

“There isn’t a city in the country that’s tried doing this yet,” said Allison. “Bristol’s really ambitious in bringing itself forwards, trying to do something new.”

Vattenfall will lead on the heating, current plans calling for a 20km pipe to carry waste heat from an incinerator at Avonmouth to the centre of Bristol. Two existing heat networks will be joined by an further six new ones, covering a large patch of the city centre. Engineering work and disruption to lay the piping will be significant but, once in place, the assets provide low carbon heating for generations.

“Once they’re in the ground, these things have a very long lifetime,” said Allison. “You look at the network that Vattenfall runs in Berlin. Bits of it are more than 100 years old. They’ve been through two world wars and the division of Berlin and all this, and they’re still sat there chugging away.”

The partners will work in parallel, targeting what they say will be an unprecedented, swift citywide decarbonisation that could serve as a template for other cities, both in the UK and further afield. While Vattenfall focuses on heat, Ameresco will look at Bristol’s built environment, directing the energy efficiency and retrofit work that will allow the district heating network to function efficiently.

“This is all part of a joined-up approach where we need to sort the buildings out,” Allison continued. “For our network, being plugged into an efficient building where the heating system is working effectively, it makes our networks more efficient…we don’t like separating the works in the buildings from the works in the network. You’ve got to think of it as one system.”

Questions have been raised, however, about the green credentials of using heat from an incinerator that burns household refuse, including plastics. The plant’s operator is exploring the potential of carbon capture and storage (CCS), but for now those plans are nothing more than a pipe dream. For Vattenfall, tapping into the incinerator’s waste heat would at least offset some of the plant’s environmental damage, although other sources of heat could potentially be used to power the network, including disused coal mines in the area.

“The process that we go through is, we look at where are the sources of waste heat that we can plug into and capture,” said Allison. “So those (Avonmouth) plants are already running and existing. The heat’s just going up the chimney for the birds. Our view there is that we can capture that and make use of what is otherwise a wasted resource.

“There will also be other sources of waste heat that we can tap into within the city, like within industry, within water treatment works, within sewers, within rivers. These are sources that you can use to increase the efficiency of heat pumps.”

If Bristol City Leap proves successful, the project could be genuinely transformative, decarbonising an entire city in a matter of a few years. It also has the power to serve as a blueprint for other cities, to showcase what is possible with the right ambition, investment, and engineering nous. According to Allison, the UK’s upcoming Energy Bill will provide additional stimulus, allowing local authorities to zone certain areas as preferable for heat networks, which will remove some of the existing uncertainty around decarbonisation strategies.

“That will be a huge thing for the market when that goes through, because it should allow us to get these things in the ground faster and have more impact against the carbon emissions,” he said. “When that does pass, there will be more cities coming forward looking for things like Bristol.”

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

Ground effect fans were banned from competitive motorsport from the end of the 1978 season following the introduction of Gordon Murray's Brabham...