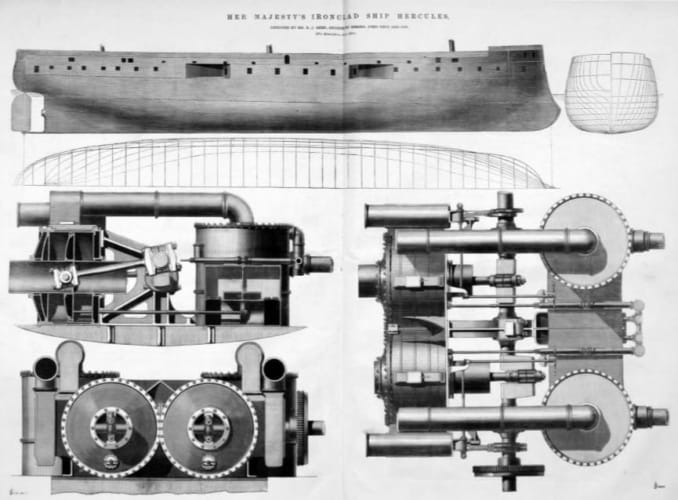

Hyperbole and awe: the Hercules was the most powerful ship in the Royal Navy, as Jason Ford writes

The Hercules was laid down at Chatham in 1886 and emerged 337ft long with a 70ft 6in beam and a displacement of 5,226 tons. The vessel was propelled at speeds up 14 knots per hour by its giant 1,200-horsepower engines.

Portsmouth’s Historic Dockyard is home to a technology first that was once the toast of the nation but would be obsolete a decade after she was launched.

HMS Warrior was built in response to developments in France where La Gloire, the first armoured wooden-hulled ship, was launched in 1859. La Gloire was the result of lessons learned during the Crimean War, a conflict in which the Russian navy made short work of wooden hulls with shell-fired guns.

From a seagoing and military viewpoint La Gloire was something of a disaster – she was only effective as an offensive force in calm seas – but her construction is said to have caused enough panic across the English Channel to start a naval arms race, which resulted in Warrior, the first of the Royal Navy’s sail- and steam-propelled Ironclads.

Warrior was, however, built at a time when the punching power of ordnance was improving rapidly and it wasn’t long before she was superseded by Hercules, a vessel described in detail by The Engineer in 1867, but seemingly – and perhaps unfairly – at the expense of Warrior.

Reflecting on Warrior, The Engineer said: “No addition had previously been made to our naval power which attracted much attention as this vessel, justly so; she forced herself upon the notice of the world, not only by reason of her enormous dimensions, her then impregnability, and her great speed, but as the embodiment of a new principle of construction. As an armoured frigate the world had not up to the time she was launched, seen anything like her.”

However, when she was commissioned “no one could assert positively that she was then impregnable to heavy guns, or that granting her armoured sides could then keep out the shot.”

The Engineer added: “The Warrior was the most powerful ship for the moment but even as she was launched men felt her reign of empire might be short.”

"In one word, she will not only be the most powerful warship in the British navy, but in the whole world"

Today’s Royal Navy is undergoing a fleet renewal that includes the first tranche of adaptable, multi-role Type 26 City Class frigates, which are expected to be in service for at least 25 years. Over 150 years previously, the Royal Navy was keen for Hercules to have a similarly lengthy service life, so the ship was designed to withstand emerging, as well as contemporary, artillery threats.

“The Hercules is a ship whose value will probably remain unimpaired for years to come,” The Engineer said. “In one word, she will not only be the most powerful warship in the British navy, but in the whole world. She will be able with ease to sink any vessel now afloat… in the navy of any other power.”

In a final patriotic flurry, The Engineer took aim at developments across the Atlantic where the US Navy was adding turret ships to its fleet, an advance that gave commanders an arc of fire and greater offensive flexibility when engaging an adversary.

“It is still clear that in the weight of ordnance and number of guns [Hercules] will carry… no turret ship has ever been built which will bear a moment’s comparison with her,” The Engineer said.

The Hercules was laid down at Chatham in 1886 and emerged 337ft long with a 70ft 6in beam and a displacement of 5,226 tons.

“Her engines are of 1,200-horsepower, expected to work up to 7,200 indicated horsepower, and to propel the ship at 14 knots per hour,” The Engineer said. “She will carry an enormous spread of canvas, and much is hoped from her as a sailing vessel.”

As with Warrior, Hercules’ trunk engines were supplied by John Penn & Sons and The Engineer, working with the illustration with which it had been provided, drew attention to small subsidiary side valves fitted on the tops of the cylinders.

“These are intended to admit steam so that the engines may be started whether the valves are or are not open,” The Engineer said. “They can be worked by one man, and the engines thus kept slowly turning while the main links are in mid-gear. Messrs Penn and Son inform us that they have never had the smallest difficulty in handling by their aid engines of 1350-horsepower. The cylinders are fitted with relief valves – Penn’s patent – which materially lessen the risk of injury from priming or any other cause which may bring water into the cylinders.”

As might be deduced, The Engineer’s ongoing coverage of Hercules came with lashings of hyperbole and awe, as the final words reveal.

“Nothing will give a better idea of the magnitude of these magnificent engines than the following statement of the weights and dimensions of some of the principal portions of the machinery: weight of crankshaft,

34 tons 16cwt; ditto of screw shaft, 24 tons; ditto of cylinder (each), 32 tons 17cwt; ditto of screw propeller, 23 tons 10cwt.”.

Radio wave weapon knocks out drone swarms

Probably. A radio-controlled drone cannot be completely shielded to RF, else you´d lose the ability to control it. The fibre optical cable removes...