It’s very easy to look upon the Victorian era as one of strict moral codes or temperance and to describe as ‘Victorian’ ideas or attitudes deemed to be old fashioned by today’s standards.

We may find it strange, for example, to think that in the 1830s temperance societies began campaigning against the recreational consumption of alcohol, with some groups seeking total prohibition whilst others advocated abstention.

READ THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE FROM THE ENGINEER'S CLASSIC ARCHIVE

The Band of Hope actively campaigned against the consumption of alcohol by children and its work continues today as Hope UK, focussing primarily on curbing drug use among young people.

Seemingly ‘Victorian’ in today’s parlance, the temperance societies were reacting – sometimes piously - to drunkenness and anti-social behaviours exhibited in towns and cities where members of the urbanised working class were seen to be developing problems caused by alcohol. They weren’t alone. In Drinking in Victorian and Edwardian Britain: Beyond the Spectre of the Drunkard Thora Hands states: “Victorians liked to drink, and they lived in a society geared towards alcohol consumption.”

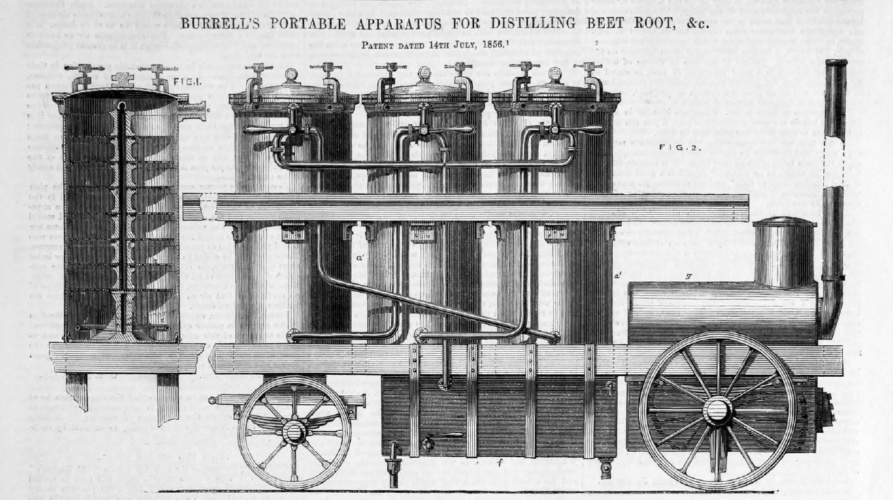

A certain C Burrell could be accused of fuelling this desire when the ‘Portable apparatus for distilling beet root’ was patented in 1856. Designed to travel to and produce alcohol on farms, Burrell’s machine used non-edible parts of beetroot and Jerusalem artichokes but, as our Victorian scribe noted, ‘other vegetable matters capable of fermenting and giving off alcohol by the treatment described may be used’.

“The roots to be used are first to be well washed, and then cut up in slices, which are preferred to be about a quarter of an inch thick,” The Engineer observed. “The cut roots are fermented in the following manner: A number of wooden vats or vessels are provided, according to the extent of distilling apparatus employed. At the commencement each vat or vessel is filled about half full of water, with as much of the cuttings of the roots as the water will cover. For each 2,630lb of the cutting of the root employed is added a small quantity of malt, and at intervals from 2 to 5lb of sulphuric acid is also added, mixed with about ten times its measure of the liquid from the tubs.

“The fermentation is generally complete in from 14 to 16 hours. The vessels or vats are covered during the fermenting process with wood covers, and the contents are kept heated by steam pipes from about 26° to 28° of Centigrade’s thermometer.”

Each distilling vessel is provided with a perforated coil of pipe through which steam is passed and the product distilled off passes from the still to the pipe, and thence to a suitable refrigerating apparatus

The stills were mounted on a carriage with a steam boiler so that the distilling apparatus could be removed from farm to farm with a view to save the carriage of the roots, and simultaneously have the residue of the roots for feeding cattle on the same farm where the roots were grown.

The apparatus shown in The Engineer consisted of three upright cylindrical vessels, but more or fewer distilling vessels could be mounted on the same carriages.

“Each distilling vessel is provided with a perforated coil of pipe through which steam is passed and the product distilled off passes from the still to the pipe, and thence to a suitable refrigerating apparatus,” The Engineer said.

Somewhat breathlessly, our Victorian predecessor added: “The arrangement of the connexions is such that the steam may be caused to enter one only of the stills, and the products of such still may then pass into the bottom and rise up amongst the matters on a series of trays contained in it, and from the second to the third and by the cocks and connecting pipes, the order in which the several distilling vessels may be used may be varied from time to time, the steam being let first into the vessel where the most spent roots are placed or otherwise, or only one or two of the vessels may be in use, if desired without employing the others.”

What the article fails to make clear is the type of intoxicating beverage produced in the mobile distillery. Luckily, Dr James Sumner from Manchester University’s Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine filled in the blanks.

“The likely answer is “anything you’d make from cane sugar”,” he told The Engineer via Twitter. “The product as it left the actual distillery was usually just sold as “spirit”. Rectifiers would buy spirit from any origin, purify it and add flavourings to make various products. A lot of it would’ve ended up as gin.”

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

Ground effect fans were banned from competitive motorsport from the end of the 1978 season following the introduction of Gordon Murray's Brabham...