On 23 April 1933 the New York Times published a news piece under a headline simply stating: “Sir Henry Royce, Auto Man, is Dead.” In the three decks of bullet points before the article proper, we are reminded in sub-editor’s telegramese: ‘Designed Motor that Carried Alcock in First Non-Stop Flight Over Atlantic,’ ‘Began as a Newsboy,’ and ‘His Insistence on Quality Led to Creation of New Standard in Automobile Making.’ The journalism is almost as finely machined as the creations of this humble ‘mechanic’, his name for ever associated with the Silver Ghost – described by Autocar in 1907 as ‘the best car in the world’ – and the Merlin V12 aero engine. It was the Merlin that provided not just the Hurricane and Spitfire fighter planes of the Battle of Britain with spectacular performance but, as Peter Reese mentions early in his biography Sir Henry Royce: Establishing Rolls-Royce, from Motor Cars to Aero Engines, “virtually every notable British aircraft during the Second World War.”

MORE FROM LATE GREAT ENGINEERS

Frederick Henry Royce was born in Alwalton near Peterborough in 1863, at a time when the United Kingdom was at the height of its imperial power under the prime ministership of Viscount Palmerston. Science and technology had advanced to the point where the Periodic Table had been established, submarines were emerging as the latest form of ocean transportation and the typewriter had just been invented. It was against this background that the miller’s son scratched a living selling newspapers and delivering telegrams after completing only one year of formal education. By the time he was 15-years old, Royce was apprenticed to the Great Northern Railway before relocating to London to work for the Electric Light and Power Company where he was chief electrical engineer for Liverpool’s first electric street-lighting system. In 1884 he started and electric fittings business making bell sets, fuses, switches and bulb holders in Manchester with his friend Ernest Claremont. Within a decade, F H Royce and Company was manufacturing dynamos, electric cranes and motors. By 1899 the re-registered organisation Royce Ltd was a publicly traded company.

During the economic downturn that followed the Second Boer War, that was exacerbated by the influx of cheap manufactured goods from Germany and the United States, Royce’s health deteriorated. Having been persuaded to convalesce in South Africa, he spent the long voyage reading The Automobile – Its Construction and Management by French engineer Gerard Lavergne. Convinced that the British lagged behind their European counterparts, he spent the early years of the 20th century experimenting with car design. Disillusioned by the De Dion quadricycle and frustrated when his tiller-steered Decauville voiturette failed to start, according to the Rolls-Royce website, “he quickly rectified the problem. But having entirely dismantled the car and examined each component in detail, he identified a host of other potential improvements. In typical fashion, he decided that rather than modifying the French car, he could build a better one himself.”

On 1 April 1904, the new Royce 10 HP car made its first run. Three weeks later, on the opening day of the Side Slip Trials endurance event, it covered the 145.5 miles from London to Margate and back at an average speed of 16.5 mph. “In an age when motor cars were both noisy and temperamental, Royce’s machine had also proved itself exceptionally quiet and utterly reliable.” He built three experimental two-cylinder cars of his own design – all called ‘Royce’ – one of which he gave to Claremont, while another was sold to another of his company directors Henry Edmunds. This sale led to the historic meeting at the Midland Hotel in Manchester between Royce and Edmunds’ friend Charles Stewart Rolls, an automobile pioneer and importer with a showroom in London. By the end of 1904, Rolls had agreed to take Royce’s entire output to be badged as ‘Rolls-Royce’ – in the process establishing one of the most enduring brand names ever created – with the former providing technical expertise while the latter bankrolled the partnership and provided the business acumen.

Rolls was later to recall: “I was fortunate enough to make the acquaintance of Mr. Royce and in him I found the man I had been looking for for years.” In fact, it is not beyond the bounds of possibility that Royce had entered Rolls’ orbit two decades before. Back in the 1870s when Royce was a telegram delivery boy at the Mayfair Post Office in central London, his beat included 35 Hill Street where the car dealer was born on 27 August 1877. As the Rolls-Royce website excitedly claims. “It’s thus perfectly possible that Royce delivered messages of congratulation to the proud parents of his future business partner.” However, their commercial association was not to be a long-lived one, lasting only a few years until 1910. This was when Rolls was killed at the age of 32 in an accident caused by the tail of his Wright Flyer aeroplane breaking off during an aeronautical display in Bournemouth.

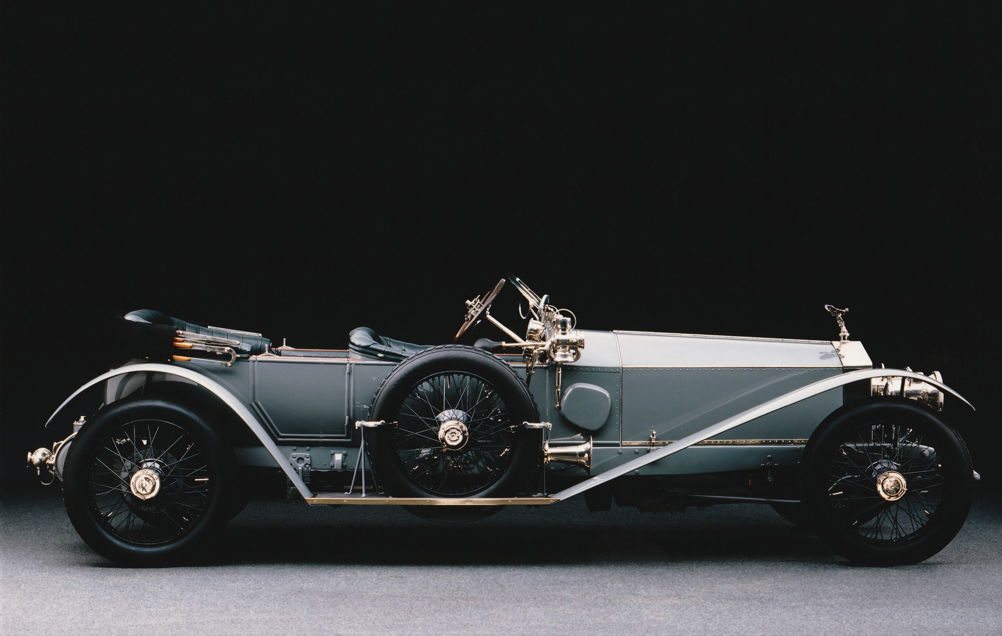

Rolls-Royce Limited came into being in March 1906. In the same year, Royce produced his six-cylinder 40/50 HP car – the legendary Silver Ghost – and designed the company’s new works in Nightingale Road, Derby. While in Derby, the engineer renowned for his gruelling work ethic became increasingly wealthy, with a villa in the south of France and a further home in Crowborough and eventually West Wittering. But his health was also in decline to the point where he was banned from visiting the factory, while nervous engineers daunted by Royce’s reputation as a perfectionist would visit him at home so that their drawings and designs could be personally approved. During this period, as well as working on cars, the company also developed the 20 litre Rolls-Royce Eagle aircraft engine (of which 4,681 were made) that was introduced in 1915 into military service during the Great War. In 1918 Royce was appointed OBE and following more success, in 1930 he was created 1st Baronet of Seaton for services to British aviation, which added the formal honorific ‘Sir’ to his name.

"The quality will remain long after the price is forgotten.” Henry Royce (1863-1933)

The Eagle engine would contribute again to the timeline of aviation after the war, when it powered John Alcock and Arthur Brown’s converted Vickers Vimy bomber that made the first non-stop transatlantic flight in June 1919. By the end of the 1920s Royce had developed his ‘R’ engine, that according to anecdotal accounts originated in Royce’s improvised sketches drawn in the sand at West Wittering while walking on the beach with his team of engineers. In 1929 it set a new world airspeed record of 357.7 mph, winning the seaplane and flying boat race Schneider Trophy. Two years later, a redesigned ‘R’ became the first engine to top 400mph. The ‘R’ engine is best known today as the foundation of the legendary Merlin that would serve to such great effect in the Second World War, powering fighter planes such as the Supermarine Spitfire.

Rolls-Royce wasn’t the only maker of luxury cars at the time. British engineer William Owen ‘W O’ Bentley’s eponymous motor company had been established in 1919 which, despite being under-financed, had become famous as a premier performance auto marque. But by 1931, and with the ailing Bentley Motor Company in voluntary liquidation, the receiver was called in and arch-rival Rolls-Royce announced its acquisition on 20th November. The new owners registered the Bentley trademark and took over the name, as well as the company’s showrooms in Cork Street, with the idea of putting a ‘hotted-up’ Rolls-Royce engine onto a Bentley chassis. Once again, apprehensive engineers took a new design down to West Wittering to be scrutinised by Royce, who approved the work after deciding that a fast open four-seater should have a means of varying he stiffness of the suspension.

Royce’s adjustable shock absorber was to be his last engineering innovation, which he persisted with despite his failing health. The man whose motto was “whatever is rightly done, however humble, is noble” died on 22 April 1933, after succumbing to long‑term illness resulting from poor nutrition in childhood and a lifetime of overwork. Even on his deathbed, he worked on his shock absorber, the last sketch annotated by his nurse. Royce, too weak to write, instructed Miss Aubin to see that the ‘boys’ in the factory received his instructions safely. As the Rolls-Royce website says, that he was still producing original ideas is a testament to his “devotion to his craft, and the breadth and brilliance of his engineering mind.” In 1962 a memorial window dedicated to Henry Royce’s memory was unveiled in Westminster Abbey – the only occasion an engineer has been honoured in this way.

McMurtry Spéirling defies gravity using fan downforce

Ground effect fans were banned from competitive motorsport from the end of the 1978 season following the introduction of Gordon Murray's Brabham...