According to the author of The Great Bridge David McCullough, there had been talk of spanning New York’s East River for ‘as long as anyone can remember’. The reason for the project never getting further than ‘just talk’ was because the stretch of water in question contained the busiest shipping lanes in the world, playing host to the largest vessels ever built. Any bridge connecting the two cities (as they were then) of New York and Brooklyn would need to be high enough to allow the masts of great ships to pass beneath. Not only would such an enterprise need to be the longest suspension bridge ever built, it would also have to withstand the Atlantic gales.

As with so many of the great 19th century landmarks, the story of the Brooklyn Bridge (that wasn’t even named formally as such until 1915) spanned the generations. Reduced to the simplest of narratives, it was designed by the immigrant Prussian civil engineer John A Roebling and seen through the construction phase by his son Washington until its official opening on 24 May 1883. But the story is in reality much more complex, and the role played by Washington’s wife Emily Warren Roebling in ensuring the completion of the 14-year endeavour – often directing operations from her husband’s sickbed – is frequently underestimated. In fact, such was her importance to the delivery of the project that Emily was the first person to cross this designated National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, closely followed by the great and the good of both cities, as well as assorted livestock.

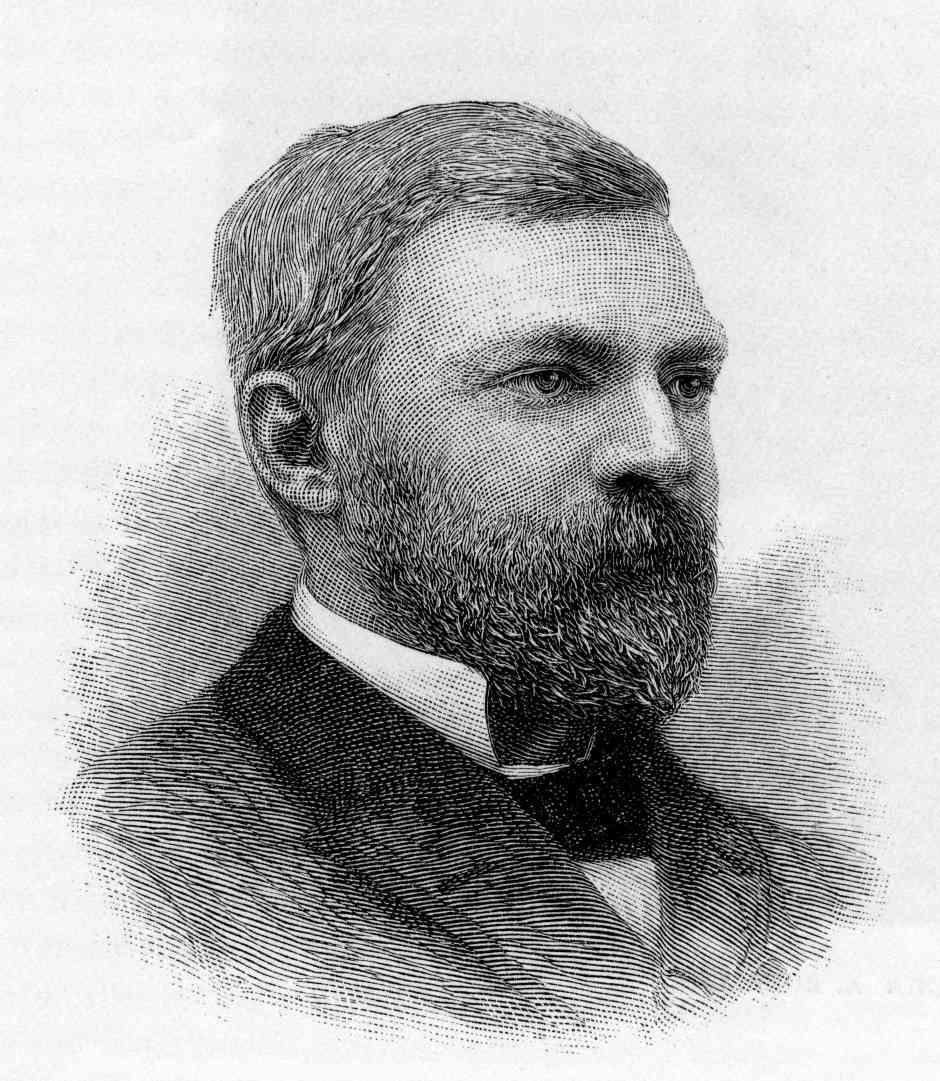

Washington Augustus Roebling was born in 1837 in the town of Saxonburg, Pennsylvania. His 21st century biographer Erica Wagner describes both time and place as, “the frontier of the United States. His father had come from Germany in 1831and had built up the American wire rope industry. So Washington went from a rural childhood to the forefront of American industry.” He also grew up in the Land of Opportunity and entrepreneurism: his father, along with his uncle Carl founded the town Washington grew up in, and his childhood propelled him in his father’s footsteps towards an education in engineering. By the time he was 17 years old he was studying at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York where he wrote a thesis entitled Design for a Suspension Aqueduct. Graduating as a civil engineer, his first main project was to assist his father on the Allegheny River Bridge in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where the young engineer first encountered wire cables in bridge construction, after which he went to work at his father’s wire mill in Trenton.

1861 saw the outbreak of the American Civil War and Roebling was quick to enlist with the New Jersey Militia before changing direction and re-enlisting with a New York artillery battery, where he became involved with suspension bridge construction, saw action in the Battle of Gettysburg and, while performing balloon reconnaissance, was to witness Robert E Lee’s Confederate Army striking northwards. After a distinguished military career, he emerged from the war having been brevetted to the rank of colonel and later becoming a veteran companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. Resuming civilian life, he returned to his civil engineering career, working with his father on the Covington & Cincinnati Suspension Bridge (that was the longest suspension bridge of its time and subsequently renamed in honour of Roebling senior), before becoming assistant engineer on the Brooklyn Bridge project (of which his father was chief engineer) in 1868.

Nothing can be done perfectly at the first trial....each day brings its little quota of experience, which with honest intentions, will lead to perfection

Washington Roebling (1837 - 1926)

John A Roebling’s idea for a crossing over the East River goes back to 1855 when, having become frustrated by the lack of progress on the Atlantic Avenue to Fulton Street Ferry, he proposed a suspension bridge comprising two granite towers and four mighty cables. Initially Roebling’s proposal was met with a distinct lack of enthusiasm by authorities from both New York and Brooklyn cities (Brooklyn wasn’t incorporated into Greater NYC until 1898). But after securing the backing of the proprietor of the Brooklyn Eagle Newspaper, Willian C Kingsley, his proposal gained traction and the New York Bridge Company was established with a $3m subscription backing from Brooklyn’s capital stock and a further $1.5m from New York. The company was permitted to recoup its outlay by levying tolls (initially pedestrians were charged one cent), while profits were capped at 15 per cent.

By 1869 surveying was underway and the informally named ‘Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridge’ that was to link the country’s first and third largest cities was to be the technological achievement of the age. Built with newly available steel wire, it would be stronger, larger and longer than any bridge yet built. The two-tier design offered cable car transportation as well as roadways for horse-drawn vehicles and an elevated promenade for pedestrians. But the project suffered a setback when Roebling senior got his foot caught between a pier and a ferry, the resulting crush injury leading to his untimely death from tetanus.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE LATE GREAT ENGINEERS

Responsibility was handed to the 32-year-old Washington, who was subsequently to become paralysed after suffering from what is now termed decompression sickness (‘the bends’), caused by working in the 3,000-ton pneumatic caissons that had been constructed to clear away silt from the riverbed. Wagner explains that in the 19th century working with compressed air was cutting edge: “Many people, including Washington, became sick as a result. The cause of the disease – nitrogen bubbles trapped in the blood – was not completely understood and so the men would ascend out of the caissons quickly. At the time it could only be alleviated with morphine.”

It was Roebling’s affliction with ‘caisson disease’ that was to lead to the increasing involvement of his wife. The arrangement was challenging for Roebling who, according to his biographer, was a ‘hands on’ engineer who would spend as much time in the bridge’s foundations as his assistants. But, due to chronic health problems, by 1875 he was unable to maintain a physical presence on the project and was badly affected by debilitating symptoms that included an aversion to both light and sound. “The only person he could stand to be near was his wife. She was an extraordinary woman, and when Washington became ill, she became his amanuensis.” Working from his bed, and effectively overseeing the construction of the world’s greatest bridge in absentia, its chief engineer dictated correspondence to Emily and briefed her for meetings with the project’s trustees. She had a natural flair for diplomacy and her ability to maintain a fragile harmony between the project’s stakeholders meant that Emily’s role in the bringing the project to its conclusion was crucial.

Given the state of his health it’s hardly surprising that Roebling fades into the background, his fame rapidly becoming overshadowed by that of the engineering icon he created. But he lived until the age of 89, taking on relatively modest appointments, such as president of the alumni association of his alma mater Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. After Emily died in 1903, he remarried five years later and was bereaved again in 1912 when his nephew and namesake Washington Augustus Roebling II perished in the sinking of RMS Titanic. For most of the remainder of his life, he pursued his hobby of mineral and rock collecting with a passion, eventually bequeathing an important collection of 16,000 specimens to the Smithsonian Institute, while his manuscripts found their way into collections at Rutgers University in New Brunswick and Rensselaer in New York.

The relative obscurity that befell Roebling was conspicuously not the fate of the Brooklyn Bridge that was to become a dominant feature of New York’s cityscape. According to the Library of Congress, “the bridge became part of the romance of New York City. Poets and artists have long found the bridge a worthy subject,” while it “continues to serve as the backdrop in countless photographs and films.” The endless affection and admiration for the bridge has led to it being honoured as one of the BBC’s Seven Wonders of the Industrial World, while it plays a prominent part in the climax of the 1998 reboot of Godzilla, although it is debatable whether Roebling’s massive stone towers with their 14,000 miles of wire could have supported the weight of the fictional mutated marine iguana. On 11 September 2001 the bridge took on a different form of symbolism as thousands of pedestrians used it to escape from Lower Manhattan in the wake of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

Invinity to build 20MWh flow battery in UK

Yuk - batteries are horrible, poisonous, short-lived and unsustainable things. It is about time that we invested in much more compatible mechanical...