While no sector of industry is untouched by the push for net zero, civil aviation - still almost entirely reliant on fossil fuels - faces a steeper and more challenging path to decarbonisation than most. And in the face of this once in a generation challenge, a host of alternative technologies - and the disruptive innovators behind them - are attracting increasing levels of attention, interest and investment from the wider aerospace industry.

One such organisation is British-American hydrogen-electric aviation pioneer ZeroAvia which - since its launch in 2017 - has chalked off an eye-catching list of green flight milestones: from the installation of Europe’s first airport hydrogen pipeline to the world’s first hydrogen fuel cell powered flight of a commercial-grade aircraft.

Earlier this summer, The Engineer caught up with CEO and founder Val Miftakhov to find out what’s next for the company and get his views on how hydrogen could transform the sector.

Miftakhov, a serial clean-tech entrepreneur; qualified pilot; physicist and former high ranking google executive - launched ZeroAvia in 2017 following the sale of his previous company, smart EV charging firm eMotorWerks. Since then, the company has grown rapidly. It now employs around 200 people, and - emboldened by a steady stream of private and public investments - confidently predicts it will be bringing hydrogen-fuelled regional flight to the masses within the next two years.

At the heart of its vision is a hydrogen electric powertrain that replaces an aircraft’s existing engines with electric motors powered by electricity from an onboard fuel cell. The company plans to launch a 600kW powertrain for 10 – 20 seat aircraft (the so-called ZA600) onto the market by 2024, followed by a more powerful 2.5MW system aimed at larger 40-80 seat turboprops (the ZA2000) by 2026. Meanwhile, in partnership with Mitsubishi-owned regional aircraft maintenance company MHIRJ, it’s also developing a variant of this more powerful system that will be retrofittable to regional jets.

It’s a hugely ambitious plan, but one that Miftakhov believes represents the most compelling solution to the green flight challenge, particularly for regional and sub-regional flight. “We looked at multiple technologies and hydrogen electric is really the best,” he said, “hydrogen is best in storing energy on a per kilogram of weight and a hydrogen electric or fuel cell approach is best at converting that chemical energy to propulsion in the most efficient way.”

In pursuit of this vision, ZeroAvia has already passed a number of significant milestones, not least through its work on the UK government funded HyFlyer programme which, in the summer of 2020, saw a six-seater Piper-M class aircraft equipped with a 250kW hydrogen electric powertrain become the world’s first hydrogen fueled commercial scale aircraft to take to the skies.

As part of the follow-on HyFlyer II project, the company is now planning to trial a more powerful 600kW hydrogen-electric powertrain and at the time of writing was gearing up to fly a modified 19-seater Dornier 228 aircraft from its facility at Kemble in the Cotswolds. “HyFlyer II is about getting to a certifiable version of the power plant….that’s the biggest priority for the company now,” said Miftakhov.

Notably, a major chunk of ZeroAvia’s activity is taking place in the UK, where more than half of its employees are based, and Miftakhov is effusive about the UK sector. “The aviation industry is obviously super important to the UK and that reflects in the policies and the attention of the government, the availability of resources, the pool of engineers to hire from, and all these great facilities,” he said. “In Europe, the UK is probably the place that’s closest In terms of ability to build an entrepreneurial company to the US and Silicon Valley as we can get,” he added.

This UK expertise has been key to addressing many of the numerous technical challenges thrown up by the development of the technology, the most significant of which, said Miftakhov, relates to thermal management.

The high efficiency of the fuel cells used means they reject less heat and the relatively small difference between ambient temperatures of around 50C and operating temperatures of around 100C creates a requirement for a lot of surface to reject and move that heat out. “That creates some interesting challenges,” said Miftakhov, explaining that the team is currently looking at a range of solutions to address this including the development of technologies that raise the core temperature of the fuel cell stacks.

Another challenge relates to the storage of hydrogen. For initial aircraft this is not such a problem, said Miftakhov: “These are slow utility airframes that are not flying that quickly so we can afford to put additional volume outside the aircraft or further tanks and not create a huge drag penalty.” However, for larger aircraft flying at higher speeds, a different approach will be required and the team is currently exploring cryogenic storage technologies for this next generation, he said.

To get the technology to the point it’s at now has not been without its setbacks. Indeed, the euphoria of that initial 2020 test flight soon gave way to concern when, in April 2021, a test plane using both a battery and fuel cell system – lost power and crashed shortly after taking off from Cranfield airport. Despite initial speculation that a hydrogen leak was to blame, subsequent investigations revealed that the issue was triggered when power was switched off as the aircraft switched from battery power to fuel cell operation and airflow to the propeller caused the motors to begin acting as generators, triggering an overvoltage protection on the inverter.

For Miftakhov, learning from mistakes like this is a necessary part of the technology development process. “I would say it accelerated the maturation of the company because we’ve learned a lot about what we need to change and how we need to progress. The fact that we are able to learn and incorporate these things into our future trajectory is also instilling confidence with investors. We are doing cutting edge exploration, and you have unknowns. How you deal with those unknowns when things happen is what’s important.”

Another way of simplifying some of these challenges and getting around the trade-offs inherent in applying new technology to existing airframes is to work with entirely new airframe designs. To this end, alongside its work with current aircraft, the company’s also exploring the application of the technology to a number of so-called clean sheet designs. “We think that with a mix of retrofit solutions, working with existing types of aircraft and several well picked clean sheet designs we have a good balance,” said Miftakhov.

Perhaps the most interesting of these projects is a recently announced collaboration with Californian firm Otto aviation, which is looking at using the ZA600 powertrain to power it’s Celera aircraft, a radical new airframe designed to reduce drag through maximising laminar flow.

In tandem with its powertrain activities, the company is also developing and deploying the refueling and renewable energy infrastructure that it believes will be key to making a success of hydrogen in the commercial aviation sector. “In the beginning of any disruptive solution introduction you can’t rely on other people to believe in it in the same wholehearted way you do...so you have to show how it’s done, and you have to push the industry towards it.” said Miftakhov.

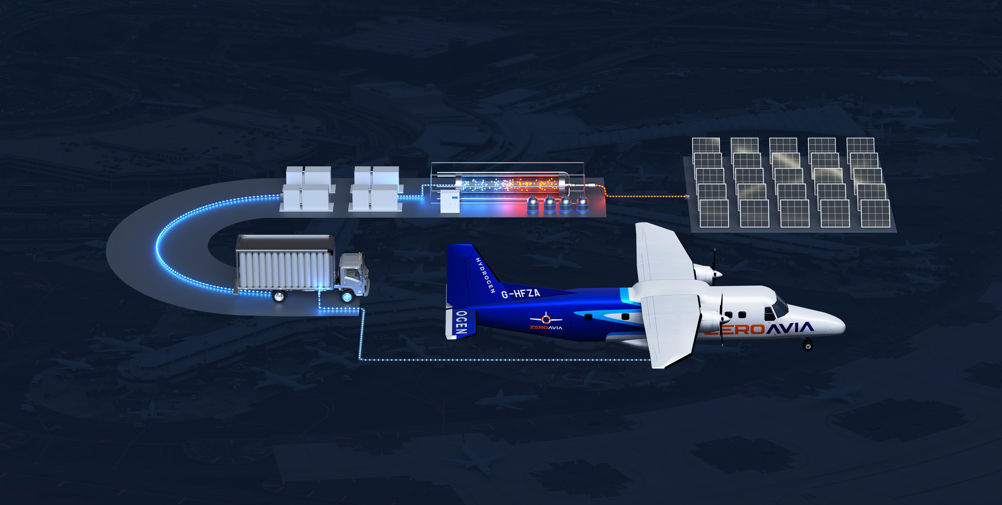

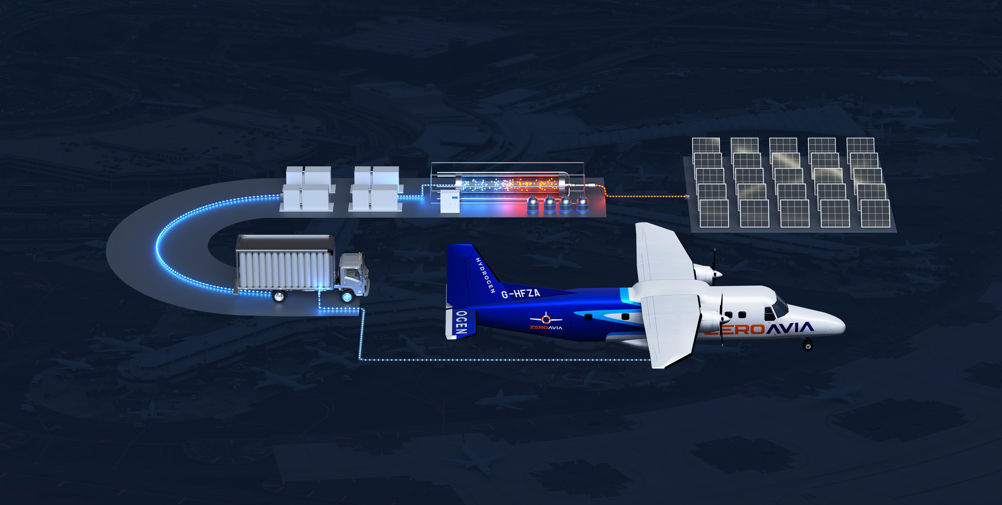

Through the first HyFlyer project, the company worked with partners including EMEC (European Marine Energy Centre) to demonstrate some of the key components of a future hydrogen airport ecosystem: including an electrolyser for green hydrogen production, a trailer-mounted compressor for preparing the hydrogen for storage, and a specially developed refuelling truck.

More recently, the company unveiled Europe’s first landside-to-airside hydrogen airport pipeline alongside its hangar at Cotswold airport in the UK, a 100-meter-long hydrogen pipeline that will help ZeroAvia demonstrate and explore the operational safety case for hydrogen pipelines and refueling infrastructure at airports.

Miftakhov sees some clear parallels between his team’s infrastructure work and Tesla’s early efforts to drive and trigger the market for electric vehicles with the development of a supercharger network. “The main problem with electric cars is charging infrastructure because people want to go places and they have a range anxiety. Tesla realised this early and said we’re going to eliminate it. I think that’s easily the main reason why they’re on top. We intend to do the same with the infrastructure here.”

Indeed, this all-encompassing approach is a key part of the company’s business model which, rather like Rolls-Royce’s pioneering “power by the hour” approach, will stretch way beyond simply selling powertrains, and also include contracts for ongoing maintenance, spare parts and fuel supply.

Returning to the EV sector and the challenges of introducing new types of vehicles and infrastructure on the road, Miftakhov believes his firm’s model is relatively risk free. “With scheduled service airlines we know what the flights are, we know the locations, and we know the volume. It’s not like we’re going to lose money on building infrastructure and then hoping to recoup it, we can be profitable from almost day one.”

And with close to 1,000 engines on pre-order, strategic investments from companies including United Airlines, IAG and Alaska Airlines, partnerships with fuel suppliers in place, and ongoing conversations with around ten airports, Miftakhov is confident that the company will soon have some tangible examples to back up its ambitions.

Microplastics evading capture in wastewater treatment

Can anyone provide a link to a credible peer-reviewed study demonstrating toxicity from microplastics? This report uses words like ´potential´ and...